Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Iterative misfires, cyclical catastrophes and perilous, treacherous pathways, breakdowns and breakthroughs. These are our modern-day incantations and necessitated methods, the magical cornerstones of an edifice of economies, social systems, personal relations, beliefs and philosophies. We are tested and fail before the gods, we demand proof of one another’s faith and fall short, strive toward integrity of intention but don’t always hit the mark. As goes the relativising liberation of “not crying over spilt milk”, so goes the invocation of cali-fornicative technologies. “Progress” these days means to project projects, cantilever life, unreservedly and constantly risk to fail. And with the crash and burn comes a freeing clearing, an identification as underdog, conjoined with an imperative to “emerge from the ashes”.

Technological development, as personal development, is often recounted as the exploitation and instrumentalisation of heroic moments, actions and individuals that ignores a long shadow of aborted initiatives, projects, flops, errors, malfunctions, as well as hidden disavowals and unreported disasters. Speculation about our future selves and tools, sometimes as irresponsible and flagrant futurism, imagines and pursues high-efficiency, self-actualised, utopian perfection. Meanwhile, and apparently contradictorily, the mantras of West-coast innovation that have swallowed the globe functionalise failure itself (“Fail Fast, Fail Often”, “Fail Forward”). In the techno-scientifically saturated culture in which we all now live, even empowered personal, emotional strength must always, and only, be accompanied with an equal measure of breakdown — weakness and vulnerability, and remaining open to the experimentalist’s unasuredness, always open to being shut-down, destabilised. Each and every aspect of our buggy little worlds and lives has to be picked at for those necessarily, and fairly obviously, present insecurities and imperfections. But what kind of odd reality have we created, in which Leonard Cohen[1] and Silicon Valley converge into some kind of omnipresent cultural kintsugi?[2] There is indeed a crack in everything, and that’s probably how the light gets in, but do we really need to fail all the time, everywhere, just so we can fail better, yet again?

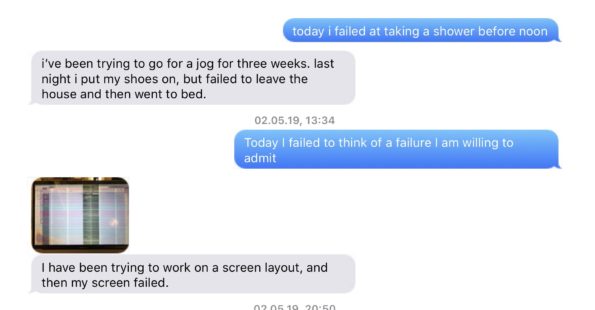

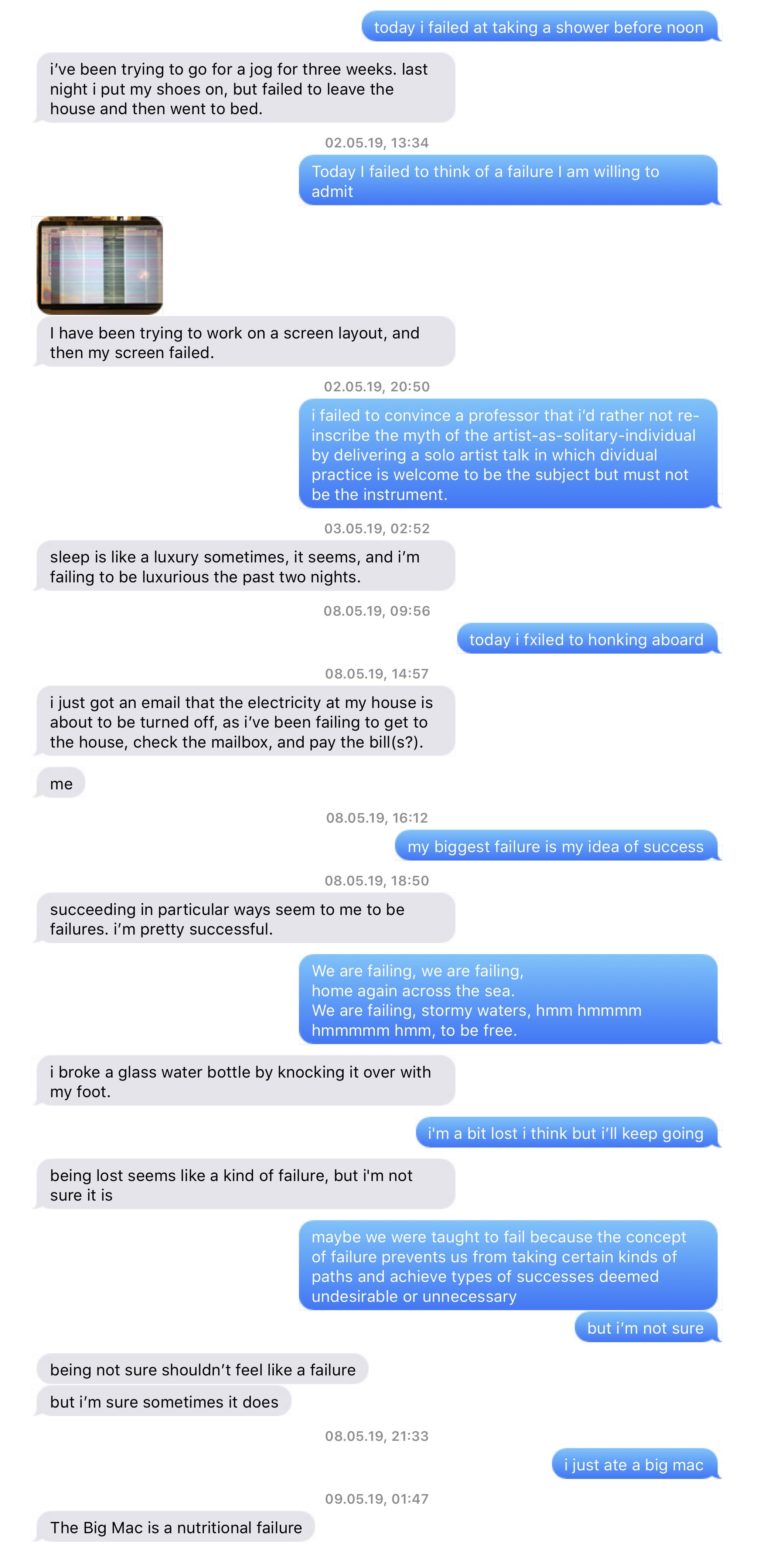

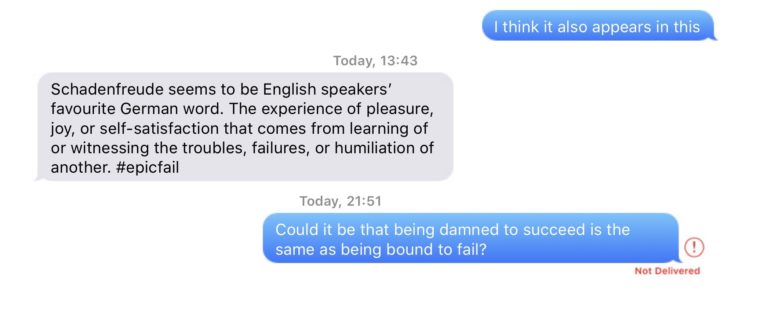

During some days in May 2019, we, Bernhard Garnicnig and Jamie Allen, attempted to get an Apple Message chat going in which we would report to one another our little, everyday failures. It seemed to us that life is just so full of little things that go wrong, so inundated by thwarted expectations, so broken by the fractured promises of people and things, that a diary of these vulnerabilities would overflow with admissions of personal disappointments in, and failures of, our selves and other(s). The exercise was a response to Vista Oral and A*Desk’s invitation and commission, which you are now reading, but it was also a response to our contemporary moment, that seems to demand continuous fault-acknowledgement, such “radical” “transparency”. With this comes the linked promise that responding to this demand will somehow alchemically improve relations and effectiveness, productivity and honour, integrity and resilience. And so, our casual, sincere little message chat listing began, and rather well.

The exercise turned out not to be quite as easy as we thought. Maybe these little failures are hard to admit. Maybe failure is created, constituted, by such admissions? We’re not sure. Our listing became a bit fraught and digressive, breaking down into youtube #fail references, as well as a few, cute, technical misfires. Communicating our failures, setup by the necessarily self-fulfilling framing of the exercise perhaps, was kind of a failure.

Maybe our co-confessional was interrupted by the smooth flows of our lives these days, which, while continuously co-creating failure in different and parallel “systems”, also seem to progress pretty fluidly. To be sure, we are both priveleged, living lives sheltered from truly fundamental failures — white, male, (over) educated, in Europe. How to fail? Where to fail? What is it to fail? Does everything fail? These questions were in our thoughts during these Spring every-days — the notion of failure becoming something of a tautology, particularly when it is difficult to figure out, as it often is, what it is that is at stake. What evolved was an evaluative perspective that is necessarily accepting, forgiving or generous, likely a survival strategy toward the hopeful co-creation of life itself, of living, in the always somewhat unconscious quotidian. Things just go, and most of the time, they seem to go, and rather well. To succeed, possibly, is to fail at imagining other outcomes, more elaborated or fulfilling experiments. To fail, then, is to succeed at creating differences that make a difference. Small miracles and little transcendences persist, in life as in technoculture — perhaps in the way that Langdon Winner described with that little conceptual chestnut “technological somnambulism”,[3] but they persist nonetheless.

Our little exercise predisposed us to the ways messaging and other communications technologies increasingly migrate into lifeworlds that are outside of logical, reasoned or technical judgement, outside of expectations and assumptions of what works and what doesn’t, external to that which succeeds, and that which fails… moving smoothly, and into every day life. The mere, unstoppable passage of time exiles our supposed failures to such a realm, one that is beyond evaluation and where everything is perfect.[4]

[1]“There is a crack, a crack in everything / That’s how the light gets in”, is a lyric from the Leonard Cohen song “Anthem”. On November 7th Leonard Cohen died, and on November 8th Donald Trump was elected president of the United State of America. Cohen’s Anthem lyric was widely circulated across the internet through social networks during this time, as a message of light and hope in apparent darkness.

[2]Kintsugi is the Japanese art of repairing broken ceramics with precious metal lacquers, a handcraft-cum-philosophy that looks at breaks and cracks, material failures and fissures as part of the history of an object, to be highlighted, cherished and treasured.

[3]Winner’s somnambulistic view of technology was his critique of the way that, in modern Western culture, our relationships to technology are seen as too obvious to merit serious reflection, i.e., constituted only as ‘making’ (only of interest to engineers and technicians) and ‘use’ (occasional, unnoticed, unnocuous, nonstructured, limited and nonproblematic interactions and occurences). Winner thought that this dream-like orientation to technologies denied how fundamental technology is to the structure and/of meaning in human life.

[4]“The mere passage of time makes us all exiles.” — Joyce Carol Oates

Bernhard Garnicnig is a research artist with a background in media design based in Basel and Bregenz. His current work focuses on the digital occupation of institutionality as artistic practice, conceptual narrations of emancipatory institutional and corporate surfaces for structures of aesthetic collaboration and earnest attempts at making paradoxical things work to see what happens.

Jamie Allen is an artist, researcher and scholar, occupied with the ways that systemic and technical infrastructures teach us about who we are. He tries foreground the importance of generosity, friendship, passion and love in knowledge practices, like art and research. Allen is Senior Researcher at the Critical Media Lab in Basel, Switzerland and Canada Research Chair in Infrastructure, Media & Communications at NSCAD in Halifax.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)