Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

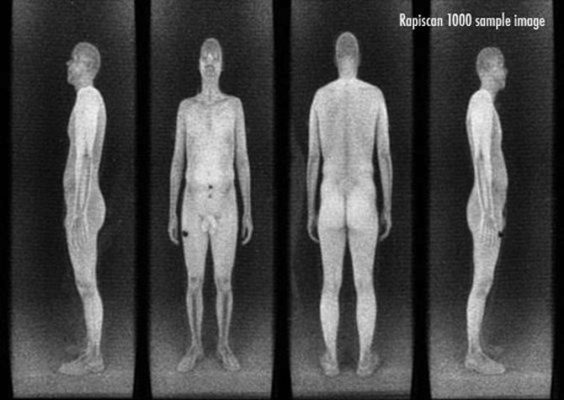

It’s not new. We live subject to a sort of technological Panopticism tecnológico. The generalisation of digital communication networks has brought with it a refinement of the strategies of control used over us. This has been possible, to a large extent, thanks to the data we provide about ourselves. The fact of living in a hyper-connected society has lead to information about our ideas, habits, and ways of life becoming increasingly exposed. By using different devices connected to the digital communication networks, we liberate, more or less consciously, data about the most varied aspects of our existence. But we don’t just reveal information when we express our opinions and tastes on social networks. We also do when we carry out supposedly trivial tasks such as, tracing a route on a map using applications like Google Maps; sharing a geo-referenced image with our mobile phone; localizing content through search engines or simply by making telephone calls or sending messages via WhatsApp. As has been warned on various occasions, the data we liberate helps to profile patterns that serve to describe our behaviour and even to predict our future conduct, data that can be used for commercial as much as for police or militaristic ends.

Without being conscious of it, we are increasingly exposed to advanced, tracking technologies. The central prison tower of Jeremy Bentham is being substituted for highly refined systems of surveillance, capable of recording with extreme precision anomalous activities in a broad range of areas. So, for example, the North American Persistent Surveillance Systems have designed surveillance systems, with cameras installed in airplanes, that make it possible to record the activities carried out by people and vehicles over various hours in an area equivalent of a small city. The ultimate aim consists in exposing us to the permanent gaze of the camera, with the dual intention of detecting any abnormal behaviour on our part and avoiding us falling into any temptation to behave untowardly.

But maybe where the new Panopticism offers its most disturbing face is in what we could define as the “collective surveillance”, where the control over us is no longer centralised, so much as is exercised in a granular fashion, by the masses connected to the Internet. Currently, our reputation is firmly conditioned by the vision offered by the rest of the individuals who coexist with us on social networks and in virtual communities; our prestige depends to a large extent on the comments and scores received for our creations on different platforms on the Internet. It is no longer the formal institutions that judge us; this task now falls on our fellow digital citizens.

On the other hand, the speed with which information circulates through the digital networks can provoke any piece of data offered by someone about us on the Internet becoming automatically exposed to the scrutiny of the masses. In the hyper-connected society, any individual with access to the Internet is a potential informant who can influence our reputation. In other words, digital technologies make us transparent and maintain us constantly exposed to the vigilant gaze of users of the networks.

As things stand, it seems evident that the majority of the population lives subject to a state of permanent control. Some subjects, however, escape the scrutinising gaze of the Panopticon, even if it is only for short intervals. Some individuals manage to occupy the dark zones, situated within the shelter of the electronic systems of surveillance. They are the people who, one way or another, situate themselves on the margins of our digitalised world: delinquents and terrorists, “undocumented” immigrants, and, to a certain extent, the unemployed. They form part of a group of individuals who hide themselves, even if it is only momentarily in the blind spots of the systems of electronic control.

Terrorists, delinquents, and “the undocumented” share in common the capacity of escaping police and judicial systems of control. They all occupy a space situated on the margins of the law. The unemployed on their part situate themselves beyond the ambit of control of the systems that govern the organisation of work and to a certain point of consumption. Their place lies beyond systems of planned production. Nevertheless, their existence is fundamental to legitimise the logic of surveillance and control of contemporary States. In accord with thinkers like Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, the exploitation of fear has become a fundamental strategy in the maintaining of order at the heart of hyper-connected societies. And, as we know the intimidation of people has repeatedly been used to impose policies of social and economic control in many nations.

In this way, the struggle against terrorism and international networks of crime have become the argument used to restrict rights and liberties and motivate laws the ultimate aim of which is to control dissent. Similarly numerous governments agitate the ghost of the unemployed to impose deregulating policies and dismantle labour rights. The fear of unemployment, or of losing work, is used strategically to undermine any act of opposition to the breaking up of the Welfare State in Europe and North America. As Hardt and Negri state: “The constant fear of poverty and anxiety about the future are the keys to creating a struggle amongst the poor for work and maintaining conflict among the imperial proletariat.”[[ Michael Hardt & Antonio Negri: Imperio, Barcelona, Paidós, 2002, p. 310.]]

It is not in vain that terror is one of the pillars upon which the control of society is based. Its existence is necessary to justify the persistence and constant refinement of the surveillance strategies that have been imposed in our time. We need to be kept constantly scared, of genuine or supposed dangers, to tolerate the constant scrutiny of our lives and the permanent monitoring of our existence. The fear of the other, be it in the form of the immigrant, the delinquent, the terrorist, the unemployed, or all four at once, is what makes us believe that control and surveillance are necessary, and which compels us to resign ourselves to its presence.

Eduardo Pérez Soler thinks that art –like Buda– is dead, though its shadow is still projected on the cave. However, this lamentable fact doesn´t impede him from continuing to reflect, discuss and write about the most diverse forms of creation.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)