Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

This was the slogan used by George Eastman in 1888 to announce a new camera system that was agile and cheap, designed by his factory — Kodak. Twelve years later he launched the Brownie camera, thanks to which anyone could take their own snapshot for a dollar. The production of images thus became accessible to all. But the real business was the control of the materials needed for developing and printing and, for at least the first half of the twentieth century, Kodak held the global monopoly on the making and printing of photographs.

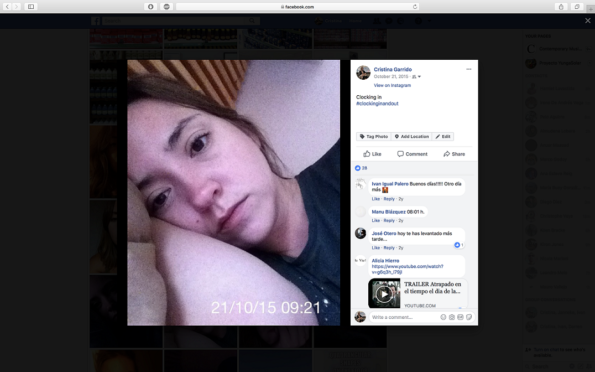

Over a century later, in October 2015, two scenes took place. First of all, Cristina seemed unable to stop playing with her mobile phone. She looked at it and let herself be looked at by it. One day she began to repeatedly take photos of herself, every morning and every evening during a whole week, methodically publishing her selfie on her social profiles.

At another moment, Ana began to follow Dalila on the networks, a young Argentinean girl who photographs herself in her home and at events. She had just published the first picture on her Tumblr.com website. 85% of the photos on her web page were of herself posing, exhibiting herself, and she has 1273 followers on Instagram and 82 subscribers to her YouTube channel.

From the first Kodak photograph to the digital profile on a network platform we have gone from having the ability of extensively multiplying pictures and their prints to constant repetition — not of images, but of the gesture of making them. The arrival of photography accessible to the masses – just as the arrival of motor cars, or of any other object that could be serially produced at low cost – was interpreted as a liberating and democratising action. The ability to create images would be emancipated, their religious and political auras would be lost, thus opening up an opportunity for revolutionary production, a collaboration between the maker and the consumer of the image, as we learnt from Walter Benjamin[1].

Benjamin quoted ‘Commune [magazine] organized a questionnaire: For whom do you write?[2]. Now the question could be, for whom do we photograph?

The two previous scenes could be mere anecdotes, and yet they have a well-defined context. Cristina is Cristina Garrido, and she was making the work entitled Clocking In and Out (2015) in which she monitored her working week. Ana is Ana Esteve Reig, and this was how she began her research for the main character in her video entitled El documental de Dalila (2016), a young girl who creates a double life for herself through a virtual profile, like a pseudo celebrity. Both suggest a reflection on this repetitive flux of images produced and distributed at one click. In 1985, Vilén Flusser imagined a society focused on our fingers and their (digital) actions, chiefly pressing buttons, and on the circulation of images (digital images too): ‘Technical images are not mirrors but projectors. They draw up plans on deceptive surfaces, and these plans are meant to become life plans for their recipients. People are supposed to arrange their lives in accordance with these designs … people no longer group themselves according to problems but rather according to technical images”.[3]

So, what meanings are created in these images and their flux? What common space is defined in their form and contents?

The repetitive display of one’s self, according to Boris Groys[4], implies servitude to a system of continuous exhibition. The body of the author is transmitted as a constructed image. The producer himself becomes the image, radically subject to the gaze of the other, to the gaze of the media. The image object would cease to exist in this contemporary operation, as the product is one’s self-design and its distribution in a complex game of displacements and replacements, deterritorialisations and reterritorialisations, de-authentications and re-authorisations. In a totally aestheticised social fabric, the production of oneself through the repetition of trivialised strategies creates a network of images destined for superficiality.

According to Hito Steyerl[5] this content would ‘present a snapshot of the affective condition of the crowd: its neurosis, paranoia, and fear, as well as its craving for desire for intensity, fun and distraction.’ Images multiplied and y replicated on all sorts of devices circulate at full speed on anonymous global networks. They are characterised by their lack of definition and quality compared with original images. To quote Steyerl again, ‘The poor image is no longer about the real thing — the originary original. Instead, it is about its own real conditions of existence: about swarm circulation, digital dispersion, fractured and flexible temporalities.’

The dematerialisation and deterritorialisation of the image refer back to a neo-liberal system. Starting from the democratisation of the possibilities afforded by the production and accessibility of images, these very characteristics of productivity generate an opposite effect in which what is eventually exploited is freedom.

My analysis has focused on content and circulation, but we could also speak of an impact on the possibility of emancipation from a formal perspective. Materially, the digital image is reduced to a series of impulses and abstract binary codes. As defined by Hansen[6], we find ourselves in a space from where the body is expelled to become a controlled hologram. This alienation would limit our ability to act according to an individual conscience from sensory perception.

Faced with this scenario, what has become of the political dimension of the image, understood as the ability to create critical thinking? How can we reconsider this repetitive productive gesture as a possibility of content rather than a print emptied of meaning? Let’s think of acting from the independent, decolonised circuits of capitalism. What is required is mobilisation, not defeatism. Duchamp proposed non-action, non-production almost as the only possible revolution for overcoming the system [7]. Yet he also used, albeit ambiguously, mass production as a form of boycott, a gesture that was extended by Beuys in his almost endless series. But does the redefinition of the print contain any other forms of critical action? The Chinese have the concept of shanzhai. As we are told by philosopher Byung-Chul Han[8], what is copied has the same value as what is original and, thanks to reflection and revision in new contexts, it becomes a place of construction, extending and improving the idea. A place for new possibilities rather than a space for cancellation or alienation. Overcoming Bartleby’s attitude of ‘I prefer not to’, there is a challenge to rethink the creation of images beyond the original, beyond the print emptied of meaning on account of its reiteration and degradation, to convert their details into a possibility of constructing new meanings starting from active collaboration rather than merely contemplative appropriation. From an enlightened critical conscience, as Marina Garcés reminds us[9], in order to ‘once again, string together the time of the liveable’.

[1] Walter Benjamin, ‘The Author as Producer’, New Left Review, 1/62, July-August 1970.

[2] Op. Cit.

[3] Vilén Flusser, Into the Universe of Technical Images, translated by Nancy Ann Roth, University of Minnesota Press, Minnesota, 2011.

[4] Boris Groys, Going Public, volume I of E-flux Journal Series, Sternberg Press, 2010.

[5] Hito Steyerl, The Wretched of the Screen, E-flux Journal, Sternberg Press, 2012, p. 41.

[6] Mark B. N. Hansen, “Les media du XXIe siècle. Sensibilité mondaine & bouclages projectifs”, Multitudes 68. Automne 2017, Paris, 2017.

[7] Maurizio Lazzarato, Marcel Duchamp and the Refusal of Work, translated by Joshua David Jordon, Semiotext(e), Los Angeles (California), 2014.

[8] Byung-Chul Han, Shanzhai. Deconstruction in Chinese, translated by Philippa Hurd, The MIT Press, Cambridge (Massachusetts), 2017.

[9] Marina Garcés, Nueva ilustración radical, Anagrama, Barcelona, 2017.

Marta Ramos-Yzquierdo is used to change and adaptation. That is why she has has worked in the most diverse fields within the art world and the cultural management. She has lived in Paris, Granada, Madrid, Santiago de Chile, a lot of years in Sao Paulo and now in Barcelona. She talks a lot with artists and other beings to seek for many questions, especially about power structures, perception and ways of acting, feeling and living.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)