Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Remember, invoke, signal, celebrate. To revise historiography, reread our female authors and artists is a pressing need – the need to revise a partial account – and responds to an urgency to find references to women artists whose oeuvre is explicitly feminist in nature and who are essential for building a genealogy of our own and that can no longer be silenced.

To speak of feminism in Catalonia is to speak of Maria Aurèlia Capmany (Barcelona, 1918-1991). It’s now 2018, the hundredth anniversary of her birth, which we must celebrate by reading and recommending her work, and, why not, by situating it in relation to other artists in order to expand a constellation of connections that denies isolation, which is the first step towards oblivion. We invoke Maria Aurèlia Capmany, whose writings seem to strike up a dialogue with the work of another key feminist artist, Eulàlia Grau (Terrassa, 1946).

The Reflections

Franco’s dictatorship prevented the existence of women’s associative movements in Spain until the foundation of the Instituto de la Mujer in 1983. The lack of an associative fabric, however, didn’t imply the inexistence of referential figures or sporadic feminist expressions that were doubly paralysed, as pointed out by Carmen Navarrete, María Ruido and Fefa Vila, by the patriarchal system and by the dictatorship[1]. In this sense, as suggested by Assumpta Bassas, ‘Maria Aurèlia Capmany is a referent in the re-emergence of feminism in the sixties in Catalonia’[2].

In 1966 Capmany published La dona a Catalunya. Consciència i situació, a book in which she interpreted the history of women in Catalonia emphasising a range of aspects that intervene in the oppression of women. In the chapter ‘Això és una dona’, for instance, she described how women become aware of their condition thanks to a definition that didn’t apply to them directly: ‘man defines and woman exercises her existence by organising her activity to fulfil the definition imposed’[3]. She also spoke of maternity and virginity, and associates male frustration with the Greek mythological image of Athena and the biblical image of Eve. Capmany declared: ‘If a woman decided to be aware, brave, fair, loyal, active, etc., she was becoming masculine. On the other hand, if she wanted to assume the role of a woman, she was supposed to abide by the programme that man had arranged for her in the worldly order. To resist was to destroy that order. To maintain the order, woman had to express her specific qualities as mother, to continue the species, and virgin, to guarantee the male individual’s intervention in this continuity’[4].

Maternity as an ideal of femininity is conspicuous in the works of Eulàlia Grau. Tumor (Tumour) relates, somewhat crudely, the image of a tumour on a ruler that is measuring it with that of two pregnant women who appear face to face, and to the sentence ‘Appearance and size of the tumour the size of an orange that has just been surgically removed’. This crudeness forms a sharp contrast with Mare feliç (Happy Mother), an ironic celebration of maternity.

Eulàlia Grau, Tumor and Mare feliç –Etnografia–, 1972.

Are these works that consider maternity an obligation imposed by society on women in order to meet presumed requirements of femininity? Or is the artist using the image of the tumour to refer to the penalisation of abortion in Spain at the time, given that it was not legalised in the country until the mid-eighties?

To return to Capmany, the author examined in depth how feminism in Catalonia, which emerged in the nineteenth century, seemed to reach its peak when the rights of middle-class men were granted to middle-class women, preserving the family as the basic structure of society and allowing the rights of the working class to be violated. According to Capmany, bourgeois women didn’t see the point of action: ‘For a woman, belonging to this class is just being there, limited to herself, with no possibility of action. Nothing she does is of any value; she cannot produce anything, she cannot communicate anything. Her field of action is limited to herself …’[5].

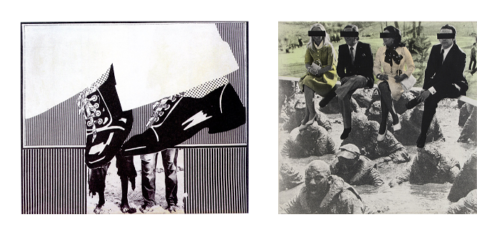

The connections between consumer society, capitalism and class difference on which Capmany insisted throughout her written oeuvre also run through the work of Eulàlia Grau. In Rics i famosos (Rich and Famous) we see two men and two women who, to judge by their clothing, appear to belong to a wealthy social class. Their eyes are covered with a black cloth and they are seated at a lower level where we see a number of people coated in mud, attempting to advance with difficulty. A similar message is conveyed by Misèria i opressió (Poverty and Oppression), featuring a pair of white trousers and two dark shiny shoes resting on the legs of two people dressed in ugly old clothes. In both cases we perceive the artist’s intention to communicate the obvious class difference and the middle classes’ lack of interest in the situation of the working classes.

Eulàlia Grau, Misèria i opressió and Rics i famosos –Etnografia–, 1972

The Encounter

Living in Barcelona, Capmany played an active part in the city’s cultural life and even wrote about some of the local exhibitions and artistic events involving Catalan female artists[6]. The aforementioned fragments and images are from years in which Capmany and Grau hadn’t yet met. It was in the late seventies when Eulàlia Grau asked Maria Aurèlia Capmany to write an introductory text for her work Discriminació de la dona (Female Discrimination, 1977) at the exhibition of the same title organised by Marisa Díez de la Fuente at her gallery, Galería Ciento, in 1980. Capmany agreed and wrote the text entitled ‘Safari fotogràfic o simplement gràfic per la selva de les imatges’.

‘A stimulus repeated and developed to excess weakens the senses, and we become deaf and blind, and lose the sense of touch and the sense of proportion and distance, and our own balance; ultimately, we lose our capacity for surprise at injustice, and therefore for protesting against injustice. EULÀLIA has opened up a path for the jungle of images and has known how to look and to choose. She knew what she was looking for whenever she has gone out in search of images; she knew that images are more than just marks distributed more or less felicitously; she knew that images aren’t innocuous and, precisely because she knew that, she was able to describe them in the jungle of newspapers and magazines.’

Safari fotogràfic o simplement gràfic per la selva de les imatges,

Maria Aurèlia Capmany[7]

[1] NAVARRETE, CARMEN; RUIDO, MARIA; VILA, FEFA, “Trastornos para devenir: entre artes y políticas feministas y queer en el Estado español” in Desacuerdos. Sobre arte, políticas y esfera pública en el Estado español. núm. 2. Barcelona: Arteleku-Diputación Foral de Guipúzcoa, Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona and UNIA arteypensamiento, 2005, p. 159.

[2] BASSAS, ASSUMPTA: “Feminismo y arte en Cataluña en las décadas de los sesenta y setenta. Escenas abiertas y esferas de reflexión” in ALIAGA, JUAN VICENTE. and MAYAYO, PATRICIA: Genealogías feministas en el arte español: 1960-2010. Madrid: This Side Up, 2013, p. 215.

[3] CAPMANY, MARIA AURÈLIA: La dona a Catalunya. Consciència i situació. Barcelona: edicions 62, 1979 (1966), p. 21.

[4] Íbid., pp. 24-25.

[5] Íbid., p. 62.

[6] BASSAS, ASSUMPTA: “Feminismo y arte en Cataluña…”, in ALIAGA, J. V. and MAYAYO, P., op. cit., p. 218.

[7] CAPMANY, MARIA AURÈLIA: “Safari fotogràfic o simplement gràfic per la selva de les imatges” in Discriminació de la dona, Pinturas ’77. Barcelona: Galería Ciento, 1980.

Marta Sesé researches and writes abour contemporary art. She lives in Madrid and works in arts publishing. She also co-manages the project Higo Mental: www.higomental.com

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)