Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

That’s what Lucretius said. There was a time when the human voice wove invisible ties with animals, fine threads of voice and melody. It was a time when they were not only raised but also spoken to in an ancient language full of harmonies, whispers and prayers.

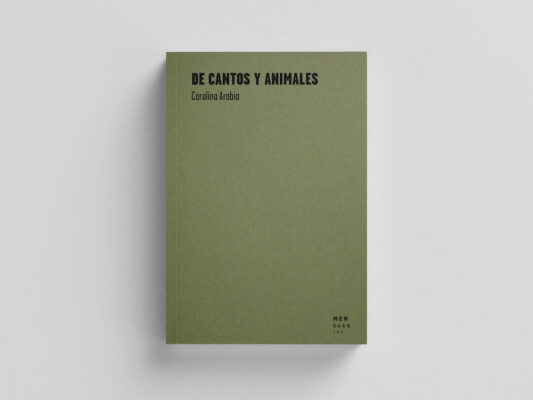

This is all, now, something like a forgotten echo, echoes of other ways of doing things. Of those echoes little remains, almost nothing, only the memory of the elderly and the stubborn search of those who refuse to let the sound of those ties die. Carolina Arabia (Buenos Aires) is one of them. For eight years, she traveled the world in search of songs that were once both tool and company, prayer and order, consolation and custom. From her travels through Colombia, Morocco, Spain and Bhutan, De cantos y animales (Of Songs and Animals) was born, a book that, like a river, carries fragments of stories and voices. Published by Ediciones Menguantes, its genius lies not only in its words but in the songs it contains. QR codes dot its pages like doors that open to other times which seem distant but are not, allowing us to hear the songs and sounds that Arabia rescued from the possibility of oblivion.

The Song of the Plains: When the Voice Calms the Cows

Reading Of Songs and Animals, I wonder when the story began, when Arabia became interested in these sung stories, in these oft whispered histories that are changing the way we do things with and how we relate to animals. In Orinoquía, the Orinoco basin between Colombia and Venezuela, Arabia heard about cowboys who sing of their horses and of women who sing while milking cows. This is an inherited art, not something learned on a whim, a technique that calms the animals and facilitates the milking. These work songs from the plains are part of a knowledge that humans and animals share in a delicate balance of trust.

In the llanero plains culture, traditional music and practices maintain a connection with the land and its inhabitants. Singing to livestock is not simply a form of entertainment, but also a way to build trust and to calm animals. This practice, known as ‘milking songs’ and ‘candle songs’, plays a role in herding livestock, especially at night. The calming melodies, a means of communication between the singer and the animal, resonate across the plains, creating an atmosphere that helps livestock management. The importance of these traditions goes beyond entertainment, they are elements of the llanero identity and heritage. Carolina Arabia, enchanted by the cadence of that history, crossed continents to encounter other traditions where humans sang to animals. That’s when curiosity sprouted in her and the question became clear: Where else do humans sing to animals?

The Geography that Influences the Song

While crisscrossing our geography, cows are herded through valleys (the Real Cañada Segoviana) to the Sierra de Gredos, to the Asturian valleys, passing through Granada, Alpujarra, and Linares.

In the south, where the light writes its own tales of landscapes, as Carolina says, it is unsure whether the story narrated comes from flamenco singing or the verses of Lorca, or if everything appears as the eye filters it. The flamenco that not only exists to entertain was also a reinforcement and support for many trades, such as street vending, iron smithing and agricultural work, and that’s where the country songs of plowing and threshing were born. Songs sung during exhausting days of work that provided stillness for both men and animals. One of the peasants once told her: “We sing to relieve the loneliness, to break the monotony of the furrow, which has to be traversed again and again from dawn to dusk, but also to calm the mules for them to work better.”

The wind from the Asturian valleys carries carries fragments of old songs with it. In Asturias, people sing both while milking the cow and when the cow is about to give birth. Arabia believes that bonds of respect and reverence are created. In some corners, the tradition of muñir songs still persists, songs that women dedicate to their cows, calling them by name.

Each word, each syllable, is a thread in the tapestry of memory, melodies transmitted by the shelter of the fire or while working the land. Thanks to Carolina Arabia, each sound is anticipated with interest for she documents the acoustic heritage, preserving sounds that are at risk of disappearing.

It was not only livestock that was once the recipient of these songs. Arabia discovered that in Asturias there are songs to guide bees to new hives. She was surprised to discover these songs sung when splitting hives. When a hive divides and the swarm follows a new queen, beekeepers spray water mixed with lemon verbena or bee sap onto the bees or place a sheet spread on the ground to lift them up to the hive. On other occasions, they hit two stones or cans with a stick to guide them, while whispering an ancient melody to them:

“Fías, a la casa nueva; fías, a la casa nueva”. (“Daughters, go to the new house; daughters, to the new house.”)

Bees are considered part of the livestock. There are areas where they are herded along with cows, so that they can come in contact with other climates and flowers. This strengthens them.

In the mountains of Morocco

The snake hunters, the Issawa, part of a brotherhood descended from the prophet, are as part of Arab culture as the shepherds. They can be found all over Morocco, everyone respects them and from a very young age they live with snakes to learn everything about them.

There was a time when the goat herds in the High Atlas of Morocco heard melodies that floated upon the air like the dust on roads, but modernity has silenced many of those songs. Arabia traveled through villages, asking for those who still played the flute to their animals, and one day, after much searching and insisting, she found a shepherd who played a flute made of cane and PVC. It might not be the most refined of instruments but the sound was the same. He played to calm the goats, to make them eat more grass, which translates into better milk and better meat. The flute, moreover, is his interlocutor in the midst of so much loneliness.

Bhutan: The Oxen that Forgot Music

In another corner of the world, between rice fields and mist-covered mountains, elderly people in Bhutan still sing to their oxen as they plow the land. They do so in a low, steady tone, a whisper to accompany the slow pace of the animals. Arabia discovered that these songs are not being sung as much. The modernization of the countryside has replaced voices with the noise of machines, and the oxen, once guided by songs, now advance in silence.

Singing endures, despite being a work tool that disappears along with certain trades. Just like the fires that the shepherds lit to fight the cold, the songs recovered by the author still persist, small and fragile but present.

As if they were a spell or talisman, the songs that have not been devoured by mechanization are installed as part of a time that continues to materialize. The sound that precedes the sound. The song that precedes the song.

Luci Romero lives in Valencia, where she has been a bookseller for as long as she can remember. She is also a cultural manager and writer. She studied Art History, but there are days when she thinks she should have studied biology or environmental sciences. It is never too late.

As a poet, she is the author of: Autovía del Este (Ayuntamiento de Cabra, 2008); El Diluvio (Amargord Ediciones, 2012); Western (Editorial Delirio, 2014); Sais. Dieciséis poetas desde La Bella Varsovia, antología (La Bella Varsovia); El tiempo de la quema (Ejemplar único, 2018); No sabe la semilla de que mano ha caído (Eolas, 2024). In 2010 she won the La Voz+joven prize from La Casa Encendida. In 2024 she published El arte de contar la naturaleza. Un acercamiento a la nature writing (Barlin Libros). She has participated in festivals such as Letras Verdes, Siberiana, Cosmopoética and Vociferio. In 2023 she was awarded the I Residence for Literature and Environment of CENEAM and the FIL Guadalajara 2024.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)