Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

It is said that the African-American writer James Baldwin (Harlem, 1924 – Saint-Paul-de-Vence, 1987) was queer before queer existed. It is true that in his essays, disqualified in academic circles for being too political or obscenely personal, this term appears in the extensive list of insults he received throughout his life: from “the ugliest boy in the world” by his father, the ambivalent “strange” of his mother, plus the insults he received on the street, “nigger,” “queer,” “sissy,” “pussy,” and “faggot,” and the nickname his partners in protest gave him, “Martin Luther Queen.” Like many who came before and after him, he had to learn to live with all those names that tried, and often managed, to wound him, and, in so doing, revealed the wounds of those who uttered them:

[A]ll of the American categories of male and female, straight or not, black or white, were shattered, thank heaven, very early in my life. Not without anguish, certainly; but once you have discerned the meaning of a label, it may seem to define you for others, but it does not have the power to define you to yourself.[1] Baldwin, J. «Freaks and the American Ideal of Manhood» (1985), en Collected Essays. Editado por Toni Morrison, Nueva York: Library of America, 1998, p.819.

Freaks are called freaks and are treated as they are treated –in the main, abominably– because they are human beings who cause echo, deep within us, our most profound terrors and desires.[2]Ídem., p.828.

The freak is, at the same time, a body sufficiently dissonant to overwhelm the binary opposition of identity, but sufficiently similar, by comparison, to confirm that our body fits into these categories. This experience of inadequacy, no matter how insightful it may be, is rarely positive. It is here, we believe, where the needfor imagination enters: blow up certain oppressive fictions, yes, and then what? (Queer, then what?) Perhaps focus on the productive modes of “de-identification”[3]Muñoz, J.E. Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics. University of Minnesota Press, 1999. Although all his life Baldwin refused to define himself as a “black writer” or as a “black gay writer,” he always referred to a myth to give meaning to his experience and desires: the myth of the androgyne.

I. «FROG-EYES»

Baldwin discovered his “ugliness” in the cruel mirror of his father, who hated his enormous “frog-eyes.” He found the counter-mirror in a movie theater in the figure of a white woman with bulging eyes, Bette Davis. “Here, before me, after all, she was a movie star: and if she was whiteand a movie star, she was rich: and she was ugly.” And despite looking like a white woman, the myth of the androgyne is foretold: “when she moved, she moved just like a nigger[4]Baldwin, J. «The Devil Finds Work» (1976), en Collected Essays, Op.cit., p.482.”.

Bette Davis was, for Baldwin, the first figure of what would obsess him until the end of his days: female in male, male in female, black in white, white in black.

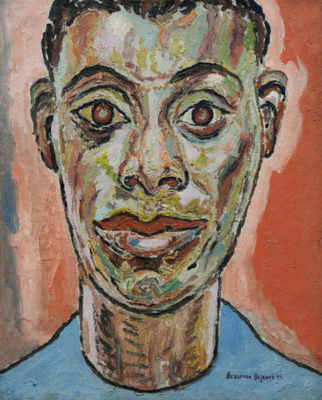

This first encounter with The Other within himself led him to the following conclusion: “I had discovered that my infirmity might not be my doom: my infirmity, of infirmities, might be forged into weapons.” Ugliness, weirdness, the obscene overflow of his body against the social distribution of the senses taught him his mission as a monstrous poet, that is, to make visible, through tangible metaphors, that which we all carry inside but which we violently repudiate. This was not a lesson that he learned alone. It was the painter Beauford Delaney, his great friend and mentor, who taught him a new grammar in which color, light and music worked in unison. Delaney, Baldwin acknowledged, taught him to “look ugliness in the face,” to confront the terrors and demons we silence within us. That gaze, and its vision of the “intangible,” was captured by the painter in his many vibrant portraits of the writer.

II. FREAKS ON FIRE

In his last essay, published in the magazine Playboy (Baldwin loved to put a mirror to the face of those who tried to ignore their own reflection), during the revival of the religious and reactionary right championed by Reagan, the writer summons all the freaks that the mob attacks:

I am speaking as the historical victim of the flames meant to exorcise the terrors of the mob, and I am also speaking as an actual potential victim.

Those ladders to fire –the burning of the witch, the heretic, the Jew, the nigger, the faggot– have always failed to redeem or even to change in any way whatever, the mob. They merely epiphanize and force their connection on the only plain on which the mob can meet: the charred bones connect its members and give them a reason to speak to one another, for the charred bones are the sum total of their individual self-hatred, externalized[5]Baldwin, J. «To Crush a Serpent» (1987) en The cross of redemption. Uncollected writings, p.204..

Beauford Delaney, Can Fire in the Park, 1946, oil on canvas, Washington D.C., Smithsonian American Art Museum

This characteristic violence of identity requires the abjection of the sexual, racial, political, religious others in order to reinforce the borders of the identity of the few. Baldwin goes even further: what the masses are really looking for is not identity, they are looking for a connection.

III. FREAK MEETS THE BLACK UNICORN

As queer as Baldwin’s imagination was, it had certain limitations, as displayed in the conversation titled Revolutionary Hope he had with the poet Audre Lorde. Baldwin speaks of blacks as “the monsters” of the American nightmare. Lorde replies:

Even worse than the nightmare is the blank. And black women are the blank. I don’t want to break all this down, then have to stop at the wall of male/female division…It’s vital that we deal constantly with racism and with white racism among black people…We must also examine the ways that we have absorbed sexism and heterosexism. These are the norms in this dragon we have been born into[6]Lorde, A., y Baldwin, J. «Revolutionary Hope: A Conversation Between James Baldwin and Audre Lorde», Essence Magazine, 1984.

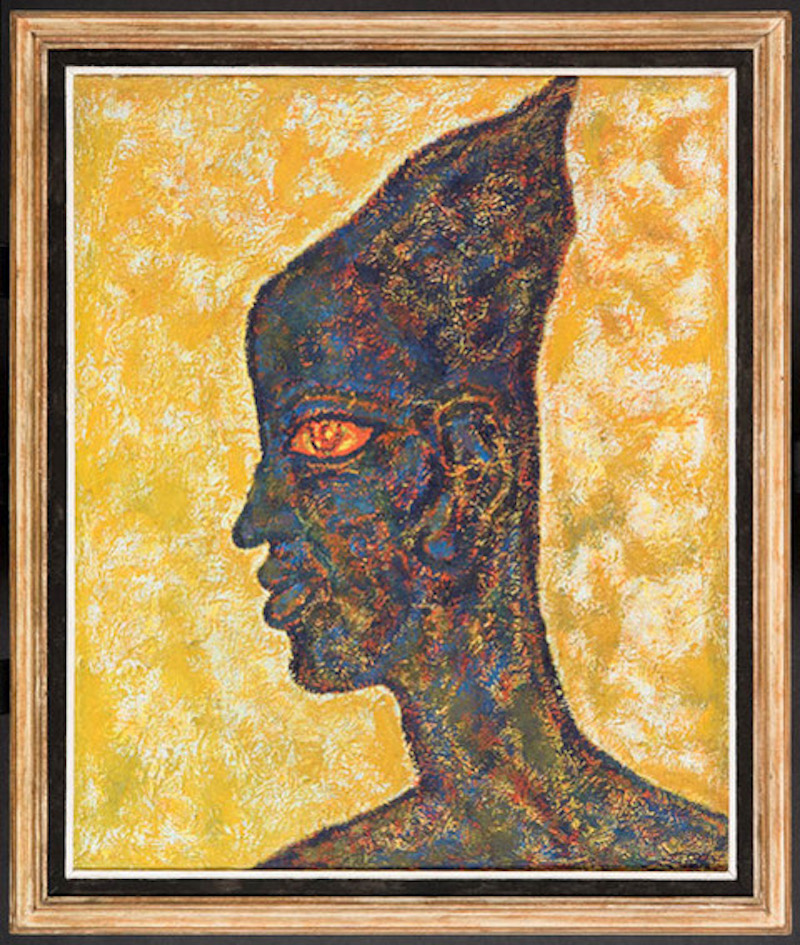

Beauford Delaney, The Eye, 1965, oil on canvas. © Estate of Beauford Delaney, con permiso de Derek L. Spratley, Esquire

There is something tangible about the dragon metaphor that drives Baldwin to change, a year later, the title of his essay Freaks and the American Ideal of Manhoodto Here Be Dragons:

Ancient maps of the world–when the world was flat–inform us concerning the void where America was waiting to be discovered, HERE BE DRAGONS. Dragons may not have been here, then, but they are certainly here now, breathing fire, belching smoke; or, to be less literary and Biblical about it, attempting to intimidate the mores, morals and morality of this particular and peculiar place.[7]Baldwin, J. «Freaks and the American Ideal of Manhood» (1985), Op.cit.,p. 816.

That which has not yet been pinned down by the (heterosexist and white supremacist) norm, that which remains “unidentified,” Baldwin names by using a metaphor, again, the monster. However, it is no longer (only) the black monster that terrifies the white man, but the lesbian dragon that Lorde taught him to see.

IV. THE MYTH OF THE ANDROGYNE

In his last work, Baldwin described a character, Terry (one of the few genderlessnames), in this way: “Terry is male or female, Black or White.” This definition echoes his own definition of the androgynous condition of all human beings:

[W]e are all androgynous, not only because we are all born of a woman impregnated by the seed of a man but because each of us, helplessly and forever, contains the other –male in female, female in male, white in black, and black in white. We are a part of each other.[8]Ídem, p.828.

Beauford Delaney, Yellow, Red and Black Circles for James Baldwin (Istambul), 1966, Gouache on braided paper. Tennessee, Knoxville Museum of Art Collection

Etymologically, androgyny refers to the One that contains Two and, more particularly, the man (andro) who contains the woman (gyne). Although this is the meaning the term is usually limited to, it can be extended to all pairs of fatally-attracted opposites: masculine/feminine, black/white. If Plato’s version of myth can be interpreted as the melancholy of separation (a body separated into two halves that embrace each other without being able to become ONE), suffering, for Baldwin, arises from the insistence on a categorical and insurmountable separation.

Spiritual and intangible androgyny is precisely what makes love (the connection) possible between human beings. It is only because we have at our disposal “the spiritual resources of both sexes” that we can love each other beyond the categories that identify and rank us. To love is, for Baldwin, to learn to see the other in oneself, not to absorb them but to welcome them in an embrace that will no longer be a fusion. “To encounter oneself is to encounter the other: and this is love. If I know that my soul trembles, I know that yours does too: and, if I can respect this, both of us can live.”

However, isn’t Baldwin’s drive towards androgyny the totalizing desire to reduce multiplicity into ONE, a desire for closure opposed to the queer movement towards deviance? Not if we assume androgyny as a myth, with ethical consequences to our ways of relating with ourselves and with others.

[Front picture: Beauford Delaney, Portrait of James Baldwin, 1945, oil on canvas. © Estate of Beauford Delaney with permission by Derek L. Spratley, Esquire.]

| ↑1 | Baldwin, J. «Freaks and the American Ideal of Manhood» (1985), en Collected Essays. Editado por Toni Morrison, Nueva York: Library of America, 1998, p.819. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Ídem., p.828. |

| ↑3 | Muñoz, J.E. Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics. University of Minnesota Press, 1999 |

| ↑4 | Baldwin, J. «The Devil Finds Work» (1976), en Collected Essays, Op.cit., p.482. |

| ↑5 | Baldwin, J. «To Crush a Serpent» (1987) en The cross of redemption. Uncollected writings, p.204. |

| ↑6 | Lorde, A., y Baldwin, J. «Revolutionary Hope: A Conversation Between James Baldwin and Audre Lorde», Essence Magazine, 1984. |

| ↑7 | Baldwin, J. «Freaks and the American Ideal of Manhood» (1985), Op.cit.,p. 816. |

| ↑8 | Ídem, p.828. |

| ↑9 | Zaborowska, M. James Baldwin’s Turkish Decade. Duke University Press, 2009,p.251. |

Júlia Ripoll has a degree in Philosophy, Politics and Economics (UC3M-UAM-UPF) and a master’s degree in Comparative Studies in Literature and Thought (UPF). She currently works as a project coordinator at the Center for Contemporary Culture in Barcelona while pursuing her PhD in Humanities at Pompeu Fabra University. Her research focuses on the critique of the foundational categories of identity (race, gender and sexuality) in the works of African-American writer James Baldwin and philosopher Judith Butler. Her fields of interest are political and social philosophy, postcolonial theory and gender studies.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)