Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

For decades, Kosovar cinema —like much of world cinema— was largely shaped by the male gaze: men’s experiences, bodies, versions of history. Women existed in those films, but often as symbols, stereotypes or moral figures. The two filmmakers in this conversation came of age amid that absence—and chose to expand what cinema can hold. They sit together not to explain their work, but to think through it —its anger, tenderness, memory, and its quiet insistence on presence.

In Zana, Antoneta Kastrati follows a woman pressured to “heal” infertility while still carrying unprocessed wartime trauma —where absence takes the form of wounds the body remembers even when language fails. In Vera Dreams of the Sea, Kaltrina Krasniqi follows a woman who negotiates grief and a patriarchal logic —where absence reveals itself as the space imposed on women by law, family and memory. Both films emerge from Kosovo’s recent history, where war, transition, and patriarchal continuity shape how memory is carried in bodies, families, and public life.

Longtime friends, they speak here about anger and empathy, visibility and erasure, and about film as a place where grief, bodies, and intergenerational conversations can finally be witnessed, preserved and carried.

Filmstill from Zana (2019) de Antoneta Kastrati

Kaltrina Krasniqi: In my twenties I had a lot of anger. I felt women were erased historically. And it took time to understand that women were erased not only here. Globally, women filmmakers were rendered invisible for a long time.

When we think about cinema here, you really have to go back to the 1960s —the first time Kosovo Albanians saw themselves on screen. But those films weren’t written by Kosovar Albanians; they were created elsewhere in Yugoslavia, and Kosovar Albanians were mostly depicted as exotic, traditional, simplified —and always through a male gaze. Later, when Kosovars themselves started making films, it’s interesting to see what kinds of stories they were telling. Again, men were at the center. They were trying to speak about where they came from, but often through the repeated trope of the suffering man. Women existed in those films, but in highly stereotypical ways: either young and naïve, or old, traditional, defenders of a male moral code.

For a long time, I used to judge those films harshly. But when I look back now, that feeling has shifted. Film is a complex and expensive practice; it rarely exists independently. It depends on state funding, on political and social climates, and all of that conditions autonomy in storytelling. During those years in Yugoslavia, there was censorship —political and artistic. There was also self-censorship. People even went to prison for certain stories. So those films often hide themselves; that’s why we can’t always connect to them directly.

Today, I think we should be generous with them. We should see them as archival material. They answer many questions about the context in which they were created.

But in my twenties, I didn’t have the generosity to see all of that. I just felt we didn’t exist in those stories. Later I realized that women didn’t exist in cinematic storytelling almost anywhere. We only started seeing women as filmmakers and authors very late worldwide. Even in countries with long cinematic traditions, women who are now considered globally central worked from the margins and were recognized decades later.

Think about Chantal Akerman, the Belgian filmmaker. She has been there since the 1970s but we only started seeing her movies 15 years ago. She’s one of the most relevant filmmakers worldwide, and she doesn’t come from the margins, she’s Belgian, French. These women just basically created from the periphery. There were so many other women from various generations, creating all the time, parallel to all of these men. But there was no platform for that storytelling.

Basically, we globally needed a political shift in order to be able to see all of those films. Only in the last two decades has there really been a shift. Once you start seeing more women worldwide, you begin to understand how our experiences connect, how they’re not so different in essential ways. There has always been an incredibly rich women’s cinematic tradition, but it didn’t have a platform, because economies and systems weren’t built to recognize women as audiences or storytellers.

Filmstill from Vera Dreams of the Sea (2021) de Kaltrina Krasniqi

Antoneta Kastrati: I relate to what you are saying, both the anger and the erasure. For me it started early, as a teenager and even before that, watching my grandmother, my mom, my older sisters, and then my own experience. You grow up inside gender rules that are everywhere, and you feel watched. Your body needs permission: how you dress, how you walk, where you go, who you talk to. People monitor you before you even understand your own body. Meanwhile your brothers and cousins move through space without thinking about it. In the 1990s, Serbian state oppression and violence layered on top of all that, so women were carrying two layers at once. And then during the war, women and children were so often the targets. After 1999 there was a fast shift, the world “opened” fast, especially for women, but so much of women’s experience still felt absent.

So for me, it wasn’t about “Oh, I want to tell the story of this woman, but it was about a way of seeing that was missing. For me that way of seeing is inseparable from the body. Mind and body aren’t separate. Experience is embodied, and violence doesn’t just happen and disappear. The body carries it. It comes back in sleep, in intimacy, in fear, in the smallest daily movements. That’s why in Zana it was important to confront what violence does to human bodies without sensationalizing it or turning it into spectacle. During and especially after the war, brutal images of violence were often exhibited and circulated without care, like proof, like content, without real respect for what they meant for the people inside them. I wanted to push against that. I wanted the viewer to feel the weight, not just understand it as information.

And with Zana, trauma isn’t only memory. It’s the body continuing the battlefield in private. Lume’s infertility and the night terrors aren’t symbolic add-ons. They’re literal. The war is still inside her. And what makes that even harder is the pressure around her. A society wants women to carry the future: children, continuity, normalcy. But it doesn’t want to fully name what the past did to them. So she’s expected to be fine, to be a wife, to be a mother, to restore order, while the real story is the unspoken brutality sitting under everyday life. And language often fails there. I say that also from personal experience, because I know what it means when language fails and the body carries what you can’t explain. Cinema can stay with it, and hold what words can’t.

Filmstill from de Zana (2019) de Antoneta Kastrati

Kaltrina: What’s unique in your approach —especially around motherhood—is that you expose how policed our imagination is. How much propaganda we’ve absorbed about what motherhood is “supposed” to feel like, and how we’re supposed to perform it publicly and privately.

And it also raises something we don’t discuss enough: loss from women’s perspectives. Wars happen, and the stories we center are rarely the women’s losses. That experience is not what we usually see.

And then it connects with Vera and her generation —how certain ideas about women’s lives and roles become completely internalized. This sense of: I sacrifice because I’m a mother, because I have children, because I have a brother —it’s what I do. The body is always there, but it’s a body that serves larger purposes: the family, the house, the continuity of things. What I found powerful is how this also sits inside a society going through radical transition, where people are constantly turned into collateral damage. And in these kinds of dramatic social shifts, it’s so often women who become the primary collateral bodies.

And what’s both moving and strange is how normalized that is—how sacrifice becomes a point of pride. I see that so clearly in my mother’s generation. It feels believable because it’s still there; it’s lived.

Filmstill from Vera Dreams of the Sea (2021) de Kaltrina Krasniqi

Antoneta: I wanted to ask you about that shift you described. You were talking earlier about being angry, In Vera you can feel the anger, but you don’t punish the older generation. You let anger and empathy sit in the same frame. There’s something really beautiful about that.

Filmstill from de Zana (2019) de Antoneta Kastrati

Kaltrina: While making Vera, I felt that cinema was a great place to preserve certain conversations. I felt we never had that opportunity before, to record our conversations. We don’t have to come up with resolutions, but we definitely need to record our intergenerational conversations—if not for each other, then for our daughters.

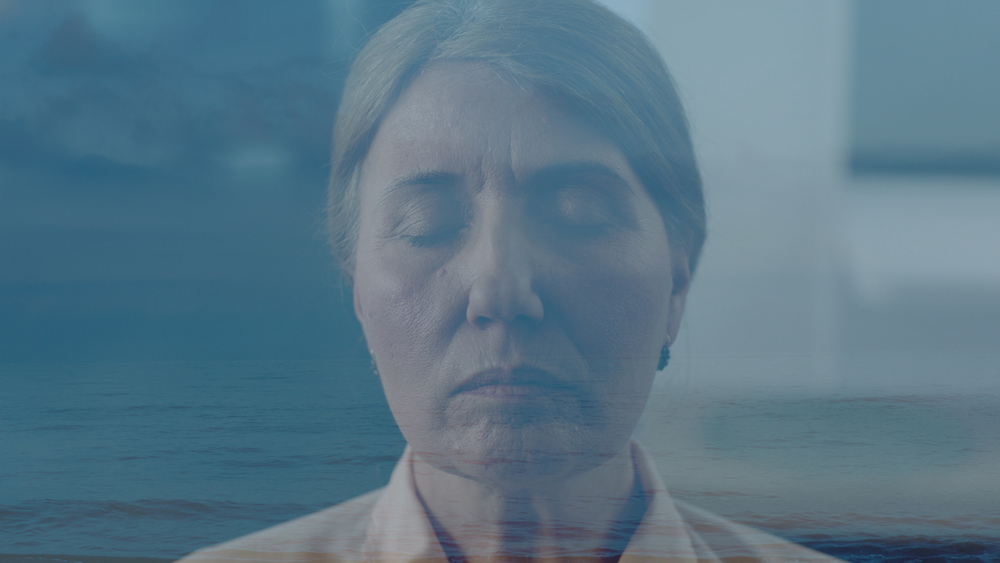

Filmstill from Vera Dreams of the Sea (2021) de Kaltrina Krasniqi

Antoneta: I relate to that so much. Making films takes time, and sometimes you need distance and time to clearly understand things.. I often think: I couldn’t have made the films I’m making now back in the 2000s. Now I’m older, I have a different lens, and in a way I’m in conversation with my past.

After the war there wasn’t space for real, honest conversation. There was one official narrative, nationalist, simplified, and even grief was hijacked. Our generation lived through the 1990s; we carry it in our bodies and memories. But the younger generation doesn’t really know that time. So for me, filmmaking also becomes a way of sharing those experiences with them, especially our daughters, something they can return to when they want to understand us and themselves, and the inheritance of trauma we didn’t choose.

And at the same time, I think our films also carry something from that period; a sense of solidarity, of dreaming big, of what we thought freedom meant. It’s not always explicit, but I feel it’s there, like a kind of glue that holds everything together. A certain wisdom.

Filmstill from de Zana (2019) de Antoneta Kastrati

Kaltrina: If you look at the films women have made here in the last 10–15 years, many begin from absence —because we didn’t have visible predecessors. Not only thematically, but in gaze: how you look at women, queer people, your country. How honest you are with that gaze.

Making films becomes a way of giving space to worlds people claim they don’t see, even though they’re present. It’s political, but also personal: you research, you write, and you end up having conversations you’ve never had before, even with your own collaborators.

Filmstill from Vera Dreams of the Sea (2021) de Kaltrina Krasniqi

Antoneta: For me, absence can also mean presence: we might not “show” something directly, but it’s there in sound, image, rhythm, time —held in the body. Triggers aren’t always external; sometimes the character carries them. Words can fail, so the film has to carry meaning differently.

Filmstill from Zana (2019) de Antoneta Kastrati

Kaltrina: And this work takes time. Sometimes your own country isn’t ready for your film when it comes out —and that can be okay. Your film enters the world immediately, but your society may need years to face and embrace it. And the beauty of film is that it can preserve a moment until people are ready to speak.

I also think of films as letters—documents for future generations. Some conversations won’t resolve in our lifetime. There’s too much to process, and our lives are limited, short. But the films can survive us, and maybe our children will connect to them differently than we can.

(Featured image: Filmstill from Vera Dreams of the Sea (2021) de Kaltrina Krasniqi)

Antoneta Kastrati is Kosovo-born writer/director and Producer. After surviving the war in the late 1990s, she began making documentary films togetherwith her sister Sevdije that addressed unexplored issues of post-war society. She was one of 8 female directors selected for the Directing Workshop for Women at the American Film Institute in Los Angeles. Her debut feature film, ZANA (2019), premiered at Toronto International Film Festival and was nominated as Kosovo’s entry for the 2020 Oscars. Antoneta was selected as Sydney Film Festival & EFP’s 2020 European women filmmakers to watch.

Kaltrina Krasniqi is an award winning Kosovo based film director and researcher working in film and digital humanities since the early 2000s. She is a founding member of the Kosovo Oral History Initiative, a digital archive dedicated to recording and preserving the personal histories of individuals from diverse walks of life. Her debut feature film Vera Dreams of the Sea premiered in the 78th Venice Film Festival and among many accolades was awarded Tokyo International Film Festival Grand Prix 2021 and Ingmar Bergman Award at Gothenburg Film Festival 2022. Currently she is in development of her second feature Bleach set to be released in 2027.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)