Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

This is not a poem, this is not an article, this is not a story. What you have in your hands is a poetic artifact in the form of a glossary, a lexicon, but also in the form of an epistolary exchange between Ale Oseguera, a Mexican poet based in Barcelona, and Laura Casielles, an Asturian poet living in Madrid. A round trip through seven concepts about migration and displacement. A necessary conversation between two voices that live between here and there, between roots and remains, and a bundle of mixed feelings that has given them a specific identity: that of displaced people. We read you.

“The foreigner is a dreamer who makes love with absence.”

Julia Kristeva

This year I won’t go home.

And yet, I am home.

We spend our lives looking for our own home, the architectural manifestation of the Self.

How to do it on diffuse terrain? How to do it on foreign soil?

Foreignness is measured in the time it takes you to arrive:

. to the records

. to the understandings

. to the distributions

. to the potato (which was yours)

. and to the air (not anymore).

And you always arrive late.

The foreign home is built with the residue of the trip:

. photographs of your parents

. the smell of boiled corn and roasted chile

. the tattooed warmth of the last hug before boarding the plane.

Home is always dressed in ultimacies, the ultimate intimacies. It is based on survival strategies. It is built with a lot of sweat and tears. Everything always changing, unstable, unpredictable, liquid. Every morning, a new, unknown roof. The foundation of the house is underground. The foundation of the home, under the skin. Home is a concept, not matter. Every year they ask you if you’re going home, even though you’re already there. Your house, even when it is purchased or rented, is never yours on foreign soil.

Friendships are like plants: you have to water them, fertilize them, prune them, protect them from pests and predators, and take them with you if you move.

But what if you can’t take them?

One morning a month, Miguel has breakfast with me, though I’m not there with him. He takes his coffee with a good dose of patience, the same patience with which he has listened to me since we were fifteen years old. He lets me talk, to tell him the details of my last fight, love affair, triumph, disappointment, joy, drama. Miguel finishes my WhatsApp podcast (two or three voice messages, 8 to 10 minutes each) and goes to work. It will take days or weeks before I receive his response, also in WhatsApp podcast format.

Skype and Whatsapp, especially, have done a lot for social relationships, but no technology has been able to deal with the problem of time zones. Eight hours difference is a lot of time. When you can chat, they are working. When they can chat, you’re already sleep. It is not easy to maintain long-distance friendships, you have to put a lot of will, effort, empathy and, above all, love into them. Positive attitude and storytelling skills also help.

Friendships mutate over the years, they grow, wither, expand, die. There are some, the most special ones, that take root forever, regardless of the soil or the country in which they are planted. They adapt to the severity of the sun or the lack of it. They survive drought, floods, distance. They bloom while you sleep. There are friendships that are like devil’s ivy or peace lilies. Such is my friendship with Miguel.

Laura says that it always seemed to her that in her small town in Asturias she would never meet anyone with the same interests. That’s why she dreamed of leaving.

I grew up in a city that, in the 1990s, had a population of about five million inhabitants. I was also convinced that I would never meet anyone with my same interests which, among many other reasons, was why I always wanted to leave. To feel like a foreigner, I preferred a place where I really was.

In Mexico, the saying goes: “Small town, big hell.”

Nightmares are not always measured in numbers. When one feels like a stranger, size is the least important thing. One’s origin, too. One dreams of destinations, of freeing oneself from labels, of realizing one’s full potential, of finding someone who can understand us even just a little bit. To paraphrase Cortázar (forgive me for being corny), we leave to find ourselves.

To conjugate verbs with vosotros is complicated. It requires an ear, practice and a lot of pretentiousness. In comparison, substitutions of slang terms are easy as pie, but also the most radical. No one just “picks up” vosotros as easy as an accent. It is always used intentionally. Camouflage is never perfect, but it helps ensure that there are no bumps or distractions on the road, so that you and your messages land where and when they should.

I started conjugating vosotros when I worked in political journalism. In politics, the difference between vosotros and usted is abysmal. Politicians always look down on you, especially if you’re an immigrant. Why is an “outsider” asking about what goes on “here”? In journalism, if there are bumps on the road, they fire you. In politics, if you don’t camouflage yourself, they will eat you alive. In Spain, not speaking their Spanish is to be ten steps behind on the road.

It’s hard to take off the mask. It gets embedded in you. One day you visit “your” country and you speak to your family and friends with vosotros. That earns you a scarlet letter on your forehead: traitor, sellout, fraud. Clara Obligado writes: “exclusion can also be found in the country of origin, where the linguistic variations of the exiled are perceived as infidelity.” Language is an extension of the homeland but also fertile ground for foreignness, wherever you are from, wherever you are.

The maxim of the newcomer is: “He who adapts, doesn’t dance.” A group of Mexicans and Colombians illustrated this to me the first time I went out drinking in Barcelona. Since I arrived, I hadn’t stopped doing mental calculations. It is well known that immigrant currency conversion always results in a loss. But not all is work and nostalgia! An immigrant also wants to have a beer, go to a concert, dance, buy a novel. The first few years, however, I didn’t buy any books. I had the entire library system in Barcelona at my disposal. I felt lucky, and wealthy.

I went to lots of concerts and plays, expensive passions that I indulged in by reviewing them in media that paid me only with a press pass. What I did give up was the movies. Cinema is extremely expensive, a luxury, just like new clothes, haircuts, fruit, rent, taxis, restaurants, coffee, tobacco and vacations. When I arrived in Barcelona in 2006, a Euro was equivalent to about 15 Mexican pesos. Today, wars have brought it to 18.60. Over seventeen years, I have seen it go up to 23.

One of those years of growth (or decline, depending on how you look at it), I returned to Mexico. Everything seemed so cheap that I got excited and told my friends: “Order whatever you want, I’ll pay. I’m making Euros.” We were at a taco stand at almost four in the morning after a night of partying.

Over the years I have stopped mentally converting my budget. The crises from the 2008 crash have given me other priorities. Although I still try to have fun. We all do. Since 2006, however, there is one thing that has not changed: I keep €1,200 in my bank account, just in case one day the (political and/or financial) crises force me to give up my European dream and I have to leave Barcelona. Returning is also a luxury.

1)

Since I moved to Barcelona, I constantly think about my own death. I always imagine dying alone. I wonder: If there is no one waiting for me, how long will it be before someone starts missing me and asks about me? What land does my corpse belong to?

2)

“To immigrate: to bury the family without being present.”

Quinny Martinez

Due to my “papers,” I spent four years without leaving Spain. During that time I missed births, birthdays, illnesses, graduations, weddings, funerals. I wondered if one day I would also experience the death of my parents from a distance.

In 2017, I had to fly to Mexico for an emergency.

I am a privileged immigrant: I was able to hug my father before his final departure.

I’ve spent every Christmas among “expatriates”: Latin Americans, Asians, some northern Europeans who, for one reason or another, stayed in Barcelona, and a group of Muslims who thought that the Christian holiday was a new experience and much more fun than a simple winter vacation in their own country. There was dinner, hugs, parties and exchange of gifts.

Consumerism aside, Christmas is the family celebration par excellence. Perhaps that is why our dinner became an exercise in patriotic nostalgia. Each one of us cooked something typical from their homeland for the occasion. It was a delicious international banquet and we ended up dancing until 5 or 6 in the morning.

Only once in seventeen years have I returned to Mexico for Christmas. Food, gifts, dancing, nostalgia and remembering those who are absent, hugging those who are present. Families are born, but they are also built based on food and unconditional love. And Christmas.

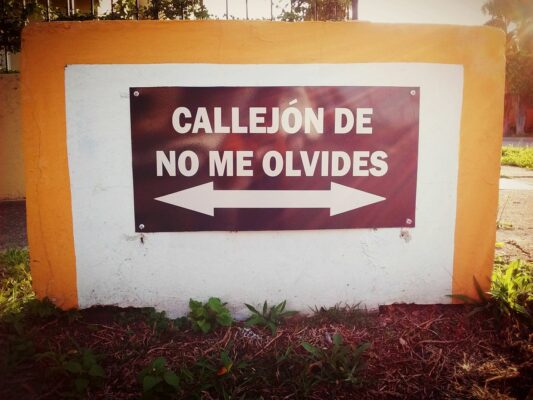

[Cover image: Streets of my neighborhood in Mexico_ Ale Oseguera].

Ale likes hybridity. In her novel, Realidad en Mono (2020), she mixes narrative fiction and audiovisual scripting. In her poetry, she combines theatrical elements with literature, creating pieces that transcend words and are also expressed through voice and body. Ale was born in Guadalajara, Mexico, and has lived and worked in Barcelona since 2006. She is the author of the collections of poems Tormenta de Tierra (2016), Un hotel de cinco estrellas sobre un cementerio (2019) and Mi rostro es un mapa de mi cuerpo (2023 ). She is also the co-founder of the collective Las Hermanas del Desorden, with whom she released the spokenword album La Musa Suicida (2019). She currently works in the field of literature as a press agent, literary critic and providing her voice in audiobooks. Since 2019 she has presented the poetry section of the program Todos Somos Suspechosos on Radio 3 (National Radio of Spain).

[Photography: Víctor Hondartzape]

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)