Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

The act of eating and food, in general, are central elements of our existence, and as such, are traversed by a multitude of cultural, sociological, economic, and political vectors, which are frequently contradictory. Probably due to this centrality that food has in life, food has always been very present in art, a terrain where its material, symbolic, and relational potential has been revealed. There are, in fact, certain similarities between the very act of cooking and that of making art; as the North American artist, Joan Jonas observed, in both practices elements are mixed together in a form of alchemy [[Linda Montano, Performance artists talking in the eighties: sex, food, money, fame, ritual, death, Berkeley, London, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2000.]].

If we revise historically the intense relations between art and food, broadly speaking and synthesising substantially we can identify three major lines of work. The most common and extensive would be that in which the act of eating and foodstuffs are taken as the objects to be represented. The most paradigmatic example would be perhaps the genre of still life, cultivated extensively in Holland in the 17th century, and revised in multiple ways by an infinite number of contemporary artists. Warhol with his Campbell soups, Claes Oldenburg with his gigantic sculptures of food, Sam Taylor-Wood with her video Still Life (2001) and the photographs of Martin Parr in his latest book, Real Food (2015), are just a few examples. Another line would be where foodstuffs, or some of their components, are used as art materials in themselves, materials with which to sculpt, draw, or paint. Within these we’d find amongst others, the works made by Dieter Roth with chocolate, the bed of Antony Gormley constructed out of over 8.600 slices of bread (1980-1981) or Subtlety or the Marvelous Sugar Baby (2014) the large sphinx covered in white sugar, which Kara Walker realised as a public sculpture in the Domino’s factory in Brooklyn. The third line of work, which is the one this article wants to focus on, is where the simple act of consuming food or drink, the feast or banquet in itself, as well as also on occasions the prior process of preparing food and serving it, is what constitutes the actual art piece.

This is, undoubtedly, a reductionist classification, for many works in which food is an essential element resist a clear pigeon holing within one single line of work of the three identified. Is the video, The Onion (1996), in which we see, in close-up, Marina Abramovic eating in bites an onion, a representation of someone eating or performance with food? Are the sweets that make up the piece by Félix González-Torres Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) (1991) sculptural materials or something edible served by the artist that the spectator can eat? And the performance Hot dog (1974) by Paul McCarthy, in which the artist filled his mouth with hot dogs and spread ketchup over his bottom and penis, is it a piece that these sauces and frankfurters are used as art materials, or an action in which the artists ingests them wildly? Despite the limited nature of this taxonomy, the three lines of work mentioned can nevertheless at least help us to understand what have been the most representative attitudes that have accompanied the artists who have introduced food and/or the act of eating in one way or another into their practice.

In relation to the third line of work, where food and the act of eating become the work itself, which, as mentioned, is the focus of this article, its origins go back to the avant-garde of the beginning of the 20th century, more specifically the 28 December in 1930. On that day Marinetti published the Manifesto of Futurist Cooking, which in tune with the spirit of rupture of Futurism and the avant-garde movements in general, proposed to slam the door on traditional cooking and even to cast off the emblematic food of the country where he grew up, pasta. Which according to the artist was stupefying, uglifying, and rendered whoever ate it slow and pessimistic. The manifesto was so radical that it makes whatever appeared revolutionary in the Nouvelle cuisine half a century later pale into insignificance. It promoted, amongst other things, the introduction of chemistry, scientific instruments and ultraviolet light into the kitchen; the invention of collections of original forms and colours in plastic that would stimulate fantasies before taste: the abolition of the knife and fork; the integration of music and poetry as well as the use of perfumes in the act of eating; and also the granting of imaginative and original names to plates, such as the “Alaska Salmon in the sun’s rays with Mars sauce”. The Futurists channelled the setting in motion of this revolutionary culinary spirit through a cookbook, the activities carried out in the Taverna del Santopalo and the elaboration of theatrical banquets in which all aesthetic and culinary norms were questioned. Given that the form in which we relate to food and the way we prepare and serve it are the reflection of social and cultural conventions, the Futurists approach to the act of eating was undoubtedly led by the desire to criticise the existent social order and to formulate new ways of being and thinking.

It is nevertheless during the decades of the 60s and 70s when the act of serving and consuming food explodes as an artistic form. A period when artists tested ways to make alternative art to that established by the institutional system and the market, where the process, dematerialisation, collaboration, and the ephemeral come into power. The act of cooking, serving and eating food is introduced with force in the performative practice of many creators. Many of these works integrate the revulsive and dissident component that the artistic cooking of the Futurists had, but what above all characterises these practices is the desire to transform certain social behaviours by promoting forms of positive socialisation, strengthening the sense of community and introducing the every day and domestic into art. These practices, like many of the works and artistic attitudes prevalent at that time, pursue the ultimate aim of eliminating the frontiers between life and art.

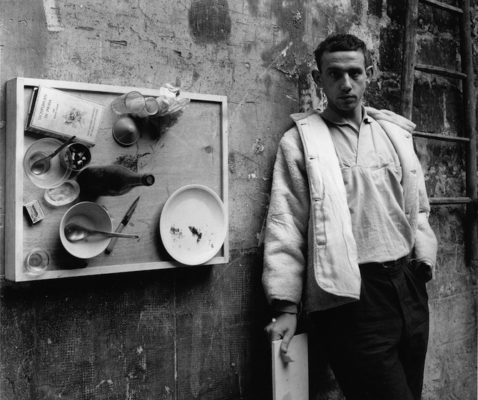

It is in this context in which some artists create restaurants that are in themselves conceptual works of art, where the food and its consumption are also artistic works. In 1968, Daniel Spoerri, the artist who coined the term “Eat Art” and defined it through his multidisciplinary artistic practice around food, opened, in Dusseldorf his restaurant-gallery. Where as well as tasting unconventional dishes, one could also buy the very table in which one had eaten, converting it into a ready-made still life in which the plates and cutlery used, and the remains of the food tasted, coexisted with personal objects of the diners, such as glasses, a lighter or a photograph carried in a wallet. These tables, in which the limits between food and remains, between process and result are blurred, also constitute a celebratory image of the culture of the after-dinner conversation, and as such, of eating as a tool for socialising. A year later, Allen Ruppersberg’s “Al’s Café” opened its doors in LA. Set up with furniture and objects that the artists had brought from all over, where as well as exhibiting their sculptures, the artists challenged conventions by serving very strange and highly indigestible plates, with outrageous names such as “simulated burned pine needles a la Johnny Cash, served with a live fern”.

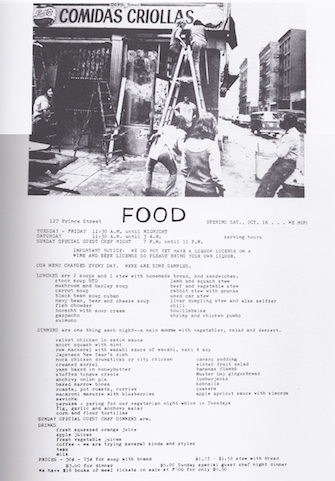

Another famous restaurant was “Food” situated on the corner of Prince Street with Wooster Street in Soho New York. Even though the history of art usually associates it principally with the figure of Gordon Matta-Clark, “Food” was undoubtedly a cooperative endeavour made possible by him as much as by another four women of the art community of Lower Manhattan: Suzanne Harris, Tina Girouard, Rachel Lew and Caroline Gooden, the latter being also the one who financed the project with money she had received as an inheritance. “Food” was a conceptual work of art but also a meeting place for the artistic community of Lower Manhattan. Founded in part with the intention of economically sustaining the members of this community and, as such, twinned with two other already iconic projects that arose in these surroundings; the space “112 Greene Street” and the magazine Avalanche. “Food” was a space of conviviality, in which legend has it Robert Rauschenberg could serve you a ‘chile’ that he himself had cooked for hours, or where you could consume amongst your colleagues one of the most emblematic snacks of the menu, the by no means easy “Matta-Bones”, a plate designed by Matta-Clark made from oxtail, roasted marrow bones, and frogs legs. “Food” was a place in which hospitality was understood and exercised as an artistic practice, but also as a platform in which food was a catalyst to activate disruptive actions and forms of thinking.

Already in the 80s, Antoni Miralda, who since the beginning of the 60s had been making dinners, banquets, ceremonies, and later street parades, in which food was an element of cohesion and social empowerment as well as a vehicle for sensory experiences and symbolic meanings, had opened in Manhattan along with the chef Montse Guillén what would become one of the most imaginative and revolutionary artistic projects of the 20th century: the International Tapas Bar and Restaurant. This iconic restaurant, in which dozens of waiters worked, through which passed figures like Andy Warhol, Pina Bausch, Umberto Eco and David Lynch, was made up of numerous bars and themed salons, each one of which could be an art installation on its own. The meals served and consumed in its salons, and the many ceremonies and performances carried out in them were a hymn to subversion, a celebration of miscegenation and unabashed fusion. Although Miralda and Guillén were the alma maters of the project, it could be said the International was also a collective work of art, generated and renewed each day as much by those worked in the restaurant as by its clientele.

Although at the front of these restaurants there were, or seemed to be, men, during this same period it was above all women artists who turned food and eating into an act of vindication and artistic creation. Traditionally, many demands tied to nutrition and the preparing of food, have been fundamentally directed at women. Only the female human body, and specifically that of the mother, can produce its own foodstuff that nourishes another human being (mother’s milk). On the other hand, the acts of cooking and serving, at least in the private sphere, have typically been far more associated with the figure of the female rather than the male. In a period of transformation, not just of art forms but also of social structures, many creators used food and the act of serving and consuming it to test new paradigms with which to rethink the feminine and the domestic, and/or to develop through these works an activism of a feminist nature.

The Waitresses were a group of women artists who carried out performances in galleries, as well as in restaurants and public spaces. Who considered that the figure of the waitress, as a woman who serves and attends the needs of diners could easily become an object of masculine sexual desire, symbolically represented the status of women in society. In their actions, The Waitresses took on the role of waitresses as an act of empowerment and social transformation. In 1979, inspired by the ceremonial installation of Judy Chicago, Suzanne Lacy, and Linda Pruess, they asked organisations of women in all parts of the world to celebrate a dinner paying homage to any woman who had been important in their culture. The result was The International Dinner Party, a collective action of successive suppers that were celebrated across the planet the length of one whole day.

Eating is in many aspects something cultural, an act tied to questions of taste, aesthetic criteria, manners, and social class. But in essence, it is something atavistic, strictly linked to survival. In Public Lunch (1971), the artist Bonnie Ora Sherk elegantly ingested a meal in an empty cage of the San Francisco Zoo while in the cage alongside a tiger shredded and devoured a large lump of meat. With this, Sherk compared and assimilated the action of consuming food as at once a civilised act with something instinctive and wild. On her part, Ana Mendieta reminded us in Death of a Chicken (1972) of the relation between food and animal sacrifice. The artist, totally nude, decapitated a chicken and holding it up in front of her let the blood drip between her legs at the height of her pubis, thereby establishing a ritualised and symbolic link between the body of the dead animal and her own.

The relation between food, body, and violence is also very present in the famous performance Ablutions (1972), carried out by Judy Chicago, Suzanne Lacy, Sandra Orgel and Aviva Rahmani. In which the artists bathed successively in large, metal tubs, one filled with egg yolk, another with blood, and another with clay. Around them there were hundreds of eggshells, ropes, and animal organs, with which they interacted in different ways, while via a loudspeaker one heard the testimonies of various women who explained bluntly and explicitly how they had been raped.

From the decade of the nineties onwards, and under the banner of relational aesthetics, artistic projects based on the act of preparing and serving food have proliferated, while at the same time they have been integrated comfortably into the artistic system. One of the maximum exponents of this line of work is undoubtedly Rirkrit Tiravanija, who promotes through food various forms of exchange and socialising. A similar project but activated through a contrary mechanism is that of Lee Mingwei, who within the framework of her project The Dinner Project, activated since the end of the 90s, invited strangers to share with him a mean that he himself prepared. His work aims to generate relations of care and positive interaction through food. But also makes manifest the tensions that run through the act of eating as something that pertains simultaneously to the private and the public sphere, as well as the tensions and protocols established between the one who offers or serves and the one who receives.

Currently, there are many initiatives, platforms, and artistic spaces that in different parts of the world and through different approaches use food as a mediating element to promote multiple forms of socialization and to stimulate at the same time lines of critical thinking around cultural, economic, ecological and ethical questions associated with eating. It is essential in this sense to highlight, without going any further, the extraordinary work that is being carried out in Barcelona, Adriana Rodríguez and Iñaki Álvarez at Espai nyam-nyam. In Pittsburgh, Jon Rubin and Dawn Weleski run Conflict Kitchen, a restaurant that periodically transforms to serve, each time, the food of a different country with which the United States is in conflict. Its culinary work is accompanied by a varied programme of activities with which it seeks to make known to the diners and public at large cultural, social, political and economic aspects of these countries, about which often only information very much tinged with governmental rhetoric arrives.

The noteworthy presence of food in current artistic practices makes evident on the one hand that the act of eating is tied to a complex framework of factors, cultural, economic and social meanings, of which it is relevant to think critically, be it through art or other spaces of reflection. However, it is important to mention the fact that the geographic coordinates through which such practices most typically emerge are those of societies in which overabundance and consumer excess lead one to forget that food is above all a basic necessity, an element essential for our subsistence distributed in a very unequal manner across the planet. In such circumstances, the emphasis of artistic practices on the relational aspect of food can also be understood as a cultural symptom or an intellectual whim of privileged social groups. Whose preoccupations revolve more around what foodstuffs to choose, from amongst the immensely varied selection on offer or how to restrict our consumption of some of them, be it for ethical, aesthetic, or health motives. Art people, who don’t have the habit or need to think of food as something we could lack.

Alexandra Laudo is an independent curator. In her projects she has explored, among others, issues related to narrative, text and the spaces of insertion between the visual arts and literature; the cultural history of the gaze; practices of resistance to the image in response to hypervisuality and oculocentrism developed from the visual arts and curatorship; and the 24/7 paradigm in relation to sleep, new technologies and the consumption of esimulants. Laudo has explored the possibility of introducing orality, peformativity and narration in the curatorial practice itself, through hybrid curatorial projects, such as performative lectures or curatorial proposals located between literary essay, criticism and curatorship.

Photo: Foto: © Ernest Gual

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)