Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Artist’s books arise as a movement that questions the limits (discursive and expositional) of art. Something Brogowski already indicated by situating them as an alternative ideology to the notion that any form of subversive art is neutralised by institutions, cultural policies or the art market [[Leszek Brogowsi “I am an interested party in the case of artists’ books”, talk presented in the presentation at Editions Incertain Sense in the Contemporary Art Centre — Ujazdowski Castle en Varsovia.]]. Nevertheless, it was artist’s publications (that originated simultaneously with a shared genealogy) and their capacity for serialisation and immediacy that led this idea into radical action.

From their beginnings, artist’s publications or magazines arose as an artistic and political movement, as a vindication of unofficial culture. They made material the defiance of a cultural system marked by elitism and the hierarchies typical of an incipient free-market for art, at the same time they served as a strategy for communication and diffusion of political and aesthetic ideas on the margins of traditional circuits. In England, for example, feminist magazines like Arena Three (1964 – 1971) instigated and edited by Esmé Langley, or Mukti (1983-1987) were crucial pieces in the protest and resistance movement of the lesbian and immigrant women communities respectively.

These publications, made within a conceptual scene, of postal art and concrete poetry, transcended the typical dematerialization of formalist questions, establishing themselves as a means for collective encounters, their critical capacity able to adapt to present culture contexts. Today we are witnessing a growing development of printed culture, in which fanzines, artist’s books, independent magazines circulate amidst ever more prominent specialised encounters like fairs, bookshops, conferences or workshops.

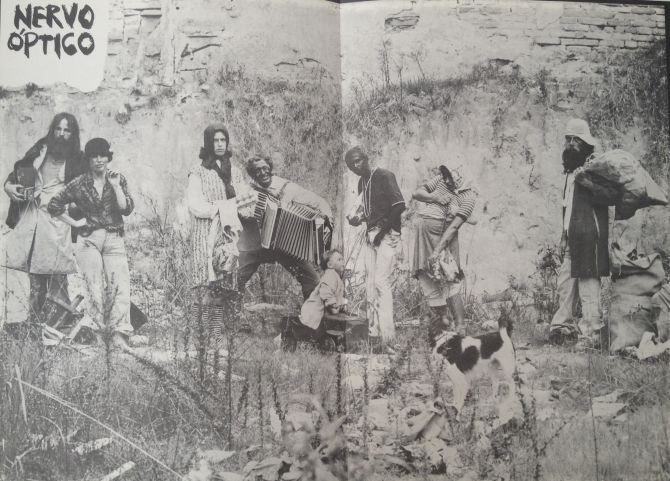

In its origins in Latin America (between the seventies and eighties) an important network for the creation and distribution of artist’s publications was generated, generally associated with conceptualism, works of experimental poetry and postal art. The critical capacity of publications like Diagonal Cero in Argentina, Los huevos del Plata in Uruguay or Nervo Optico in Brazil, in periods of military dictatorships and political persecution, were central points in the Latin-American movement. The Argentine Edgardo Antonio Vigo, in the editorial of the second issue of his pioneering magazine WC (1958-1969), indicated the importance of the multiple as democratic and direct art, reinforcing his premise to reach a social sphere through an individual (art) work. The publications guided by other Latin-American artists both within and beyond the continent, such as those of Clemente Padín, Raúl Marroquín, Martha Ellion, Felipe Ehrenberg, Ulises Carrión or Guillermo Deisler were based on this idea.

In Europe and the United States, these magazines were characterised by their proposals to break with formalism seeking a redefinition of the materiality of the work, as well as the dynamics of work-artist-spectator. Such was the case of the pioneering magazine Semina (1955 – 1964), a hand-made edition published by Wallace Berman in California. On their part, the publications edited by Seth Siegelaub between 1968 and 1972 in New York and the Art & Project Bulletins, regularly published in Amsterdam between 1968 and 1989, also fulfilled a critical function by replacing the gallery or institutional space for one that was at once autonomous, personal and public. Robert Barry made this proposal in the Bulletin nº17, in which he wrote only the text During the exhibition the gallery will be closed[[December, 1969]].

During this same time, the ex-Yugoslavian countries lived through the preamble to the wars of the nineties. The emergence of a strong nationalist discourse, the economic difficulties, and the complex political schema experienced in the socialist republics, that configured this territory (not aligned with the socialist bloc of Eastern Europe) gave rise to a context of artists that disassociated themselves from the homogeneity of the official discourses. Who initiated a provocative practice, activating collective spaces in their questioning of the social role of art and the artist as a mediator. The artistic generation that configured the so-called New Art Practice brought art to the street in the form of performances and interventions that sought a direct interaction with the people and the production and circulation of artist’s books and magazines became as much an artistic strategy as a form of documentation and diffusion.

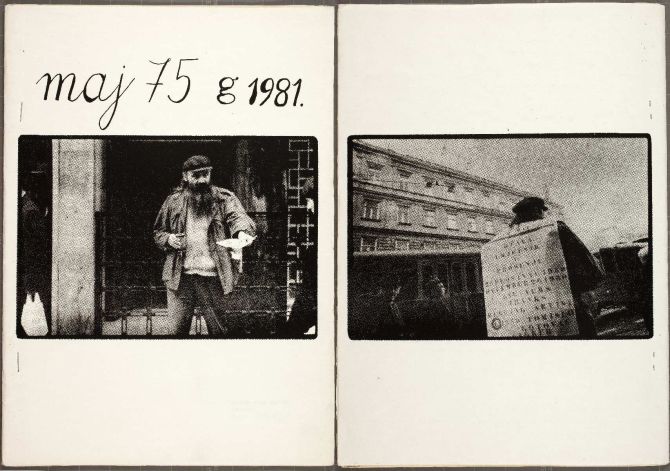

The Croatian magazine Maj 75 (Zagreb, 1978 – 1984) is an important example of the aesthetic and social concerns that mobilized this scene to experiment with the spaces, language and the processes of democratization of the work of art. Created by the collective of conceptual artists “The group of six artists” (Boris Demur, Željko Jerman, Vlado Martek, Mladen Stilinović, Sven Stilinović and Fedor Vucemilović), Maj 75 manifested itself as an alternative to the exclusivity of the artistic institutions. In the social scene in which this publication developed, the search for a zone of contact would become a central point for creation, and artistic exchange. Hence, one of the key preoccupations of this time was the question of the individual body against the social corpus. Equation in which questions arose pointing to private and public space (as a social space), or as the Polish artist, Ewa Partum proposed the “legality of space”. In this sense, Maj 75 functioned as a public space in which as they proposed in the first edition of the magazine, the information would become a work of art in itself, and the publication a space for group encounters.

Today, the creation of publications as much as the appropriation of mass press media and serials continue to be valid strategies with which to reach a social sphere. Remember the advertisement “Arresten a Kissinger” that Alfredo Jaar published in the German sensationalist newspaper taz. Berlin in 2012 once again as a space for public encounters at a specific time.

As a new editorial and artistic genre, these magazines redefined artistic production as much as its distribution, documentation, and circulation, proposing an alternative and critical space for the diffusion of ideas and works. They remodelled in a transversal way the projection and perception of the work of art and the exhibition in society. They placed on the table issues currently of interest: key questions surrounding the dynamics between the curator (editor), the artist (author) and the public (reader); about the exhibition as an aesthetic experience and the artistic medium as a tool for communication and social change.

Culture in print has not died. Contexts, urgencies, and with them aesthetic strategies have changed, but they continue to be a radical gesture, which in the context of the digital era, transforms into a space of resistance, seeking –still- in the printed page an experience at once collective, critical, and autonomous.

Daniela Hermosilla is an artist and art historian, depending on the moment one more than the other. She observes, writes, makes and investigates artist’s publications, from her doctoral thesis as well as within her work in the collective Greta Rusttt. She considers this permanent mobilization between theory and artistic practice essential and inseparable to establish her critical stance in a transversal way.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)