Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

A conversation with Sabine Langen-Crasemann, Sandra von Halem, and Karla Zerressen about two decades of collection work at the Langen Foundation in Neuss (Germany), Ascona (Switzerland), and their ideological connections to Japan.

The collection of Viktor and Marianne Langen includes around 350 works of Japanese art from the 12th to the 20th century, including religious art, Jomon ceramics, masterpieces of the Kano school, and 19th-century genre painting. The Langens acquired their pieces directly from Japan, reflecting their appreciation for aesthetic and cultural authenticity. Today, the collection is continued by their daughter and granddaughters. On the occasion of its 20th anniversary, the exhibition Three Generations – One Passion was held, focusing on the intergenerational dialogue of the family in relation to art. In conversation with Sabine Langen-Crasemann, Sandra von Halem, and Karla Zerressen, Arts of the Working Class aims not only to shed light on the family values that shape the collection but also to raise the question of art’s role as a tool for contemplation and societal reflection in today’s world. We want to understand how the spirit of today’s art world influences the collection and what it means to continue a collection across generations, especially in a time characterized by global upheavals and profound ethical questions.

Sabine Langen-Crasemann, Sandra von Halem & Karla Zerressen. Photo: Susanne Diesner

Marianne Langen emphasized the importance of beauty over market value. How does this attitude shape your collection work today? Do you see similar approaches in the contemporary art scene?

Karla Zerressen: Especially with the Japanese works, my grandparents didn’t just collect for beauty, but also for completeness. My grandfather was deeply engaged with Japanese art and culture.

Sabine Langen-Crasemann: Beauty alone is not decisive. For example, my father placed great value on color compositions, which often led to disagreements with my mother, but the quality was as important to him as the historical and social value these works held. He developed a keen eye for art through many museum visits, but also through his work with people in Japan.

Sandra von Halem: When they started collecting Japanese art, these works didn’t have much market value. Japanese dealers were willing to sell a lot back then. This has changed today, as there is a greater awareness of provenance.

How important is this ethical aspect to you compared to commercial acquisition methods today?

KZ: In the 1950s and 60s, there was no international art market for Japanese art, yet my grandparents collected with great respect for Japanese culture.

SL-C: A few decades later, experts from Japan assessed our collection and were impressed by the quality. My parents knew how to recognize what was artistically and socially relevant.

Were there conversations in your family about art or specific works?

SL-C: Art historical discussions were rare, but respect for the works was always present. It wasn’t until experts visited that we fully realized the extent of the collection. For example, a 23-meter-long hanging scroll was only partially unrolled because of its size. Such pieces were often shown in the museum in Ascona.

TAWARAYA SÔTATSU STUDIO, “Folding screen with painted fans”. Edo period, 17th century

And how has the collection influenced your work today?

SL-C: My father was still heavily involved in the company when he began collecting Japanese art. Later, after selling the company, classical modernism became the focus. Japanese works were less present for a time, until the museum in Ascona opened. The building where the Japanese collection is shown became the central location for these works.

SvH: The contemporary art we collect today follows different premises.

What are they?

KZ: There has always been a societal and ethical awareness. The Langen Foundation also reflects the trade relations between Japan and Germany, as well as the family’s role in North Rhine-Westphalia.

With whom did you share this awareness?

SvH: In the past, societal conversations took place in small circles. Topics like economic change, labor struggles, the Düsseldorf Art Academy, the student movement, the environmental movement, and political crises were important, but it wasn’t until the opening of the Langen Foundation 20 years ago that the collection became public and our societal responsibility became tangible. Even though we don’t have comprehensive expertise in Japanese art, we were always aware that we had brought something special into this context. One of the oldest paper scrolls we own is kept in a small wooden container and was transported from village to village back then.

SL-C: My mother wanted to present Japanese art in Germany because it was rarely shown here. She was particularly focused on the appreciation for craftsmanship and minimal drawings. At the same time, my father wanted to gift the collection to Monte Verità in Ascona. He also drew parallels between Japanese and European spirituality in the art and wrote a book about 1000 years of Japanese art.

“Many arrive stressed, but when they enter the house, they find peace.”

YAMAGATA SÔSHIN (1818-1862), “Procession of insects as feudal lords”. Edo period, first half of 17th century

Monte Verità was also meant to be a place where the collection should reside, which highlights the connection between architecture, art, and spirituality. Do you see parallels between the minimalist aesthetic visible in Tadao Ando’s architecture and the works in your collection over the decades?

KZ: I think my grandmother fell in love with Ando’s design for this reason. It’s not just the exterior of the building but also the idea behind it. Ando wanted the path to the building to be part of the experience, a kind of separation from the outside world. You leave your daily worries behind and enter the building with a clear mind. You can see this with the visitors as well. Many arrive stressed, but when they enter the house, they find peace. The space and environment practically demand this tranquility. It works very well – also with the Japanese art and contemporary works like Troika, a group of artists currently presenting a major exhibition at the Langen Foundation.

SvH: My grandfather would have liked the current Troika exhibition because it deals with new technologies and contemporary issues. There’s a post-capitalist critique that is felt in the exhibition. It has something dystopian, but also contemplative. Particularly the room downstairs with the water and minimalist staging. Not much happens, but the effect is incredible. It’s like in Shintoism, which is deeply connected to nature. How could a postmodern interpretation of the Shinto-inspired works in your collection contribute to the current societal debate?

SvH: The peace and reflection opportunity is something many visitors appreciate at the Langen Foundation. They see the Japanese collection and recognize the connection to contemporary works. It keeps drawing visitors back because they feel these connections.

KZ: There are many connections between Japanese and European art. The influence of Japanese painting on European artists is well documented. What fascinates me most about Japanese culture is that despite the early Chinese influence through Buddhism, Shintoism was never displaced. There was a transformation in spirituality, but Shintoism remained at the core of Japanese culture and is strongly connected to nature. This is also reflected in Ando’s work, even if his work is perhaps more influenced by ecological and architectural debates. This postmodern interpretation is also visible in our collection and the current exhibition.

Can you tell us more about your connection to ecological debates, which are very present in the Troika exhibition?

KZ: These are topics that were also the focus of the Julien Charrière exhibition and are now being revisited with Troika. It’s about how humanity destroys its habitat and nature, and thus itself. Both exhibitions address these issues in a subtle, aesthetically pleasing way. When you watch the video where the last tree on Earth is felled, the drama of this destruction becomes very clear – without being preachy. It’s about sharing an awareness of our time of crisis with visitors without making them feel guilty, but simply pointing out what is happening in the world. This place was particularly important for Ando because he valued closeness to nature. This appreciation comes from the Hombroich island, where art and nature are closely connected. My mother’s house, which my grandparents built, is also situated in a beautiful landscape. My connection to nature is deeply rooted, also through my children, who make me think about their future.

SL-C: You can’t close your eyes to these topics nowadays. In art, we often show these issues subtly. The images of storms by Troika are beautiful, romantic, but they point to the destruction of nature. It’s important to start these discussions, but without a raised finger. Art can raise awareness of problems without lecturing.

KZ: We don’t have great inhibitions, so visitors are confronted with topics that may not be pleasant, but they think about them. We are a private exhibition space, which means we make many decisions from the heart. This gives us freedoms that other institutions might not have.

SvH: For the exhibition on our 20th anniversary, we also showed what was happening in different cultures at the same time. Visitors could see how art from Japan, India, or Oceania developed alongside European art. We enjoy living with these windows to other ways of life.

How would you summarize the contribution of the collection to the reflection on social hierarchies and structures?

SL-C: Art is important for the well-being of people, especially in these difficult times. If our visitors feel this and leave with a sense of renewal, we have achieved our goal.

KZ: Everyone should feel welcome here, regardless of age, gender, or financial background. We want to be a place of diversity and reflection for all.

SvH: In a perfect world, we could probably do even more. But for what we’ve created here, I’m very grateful to my family.

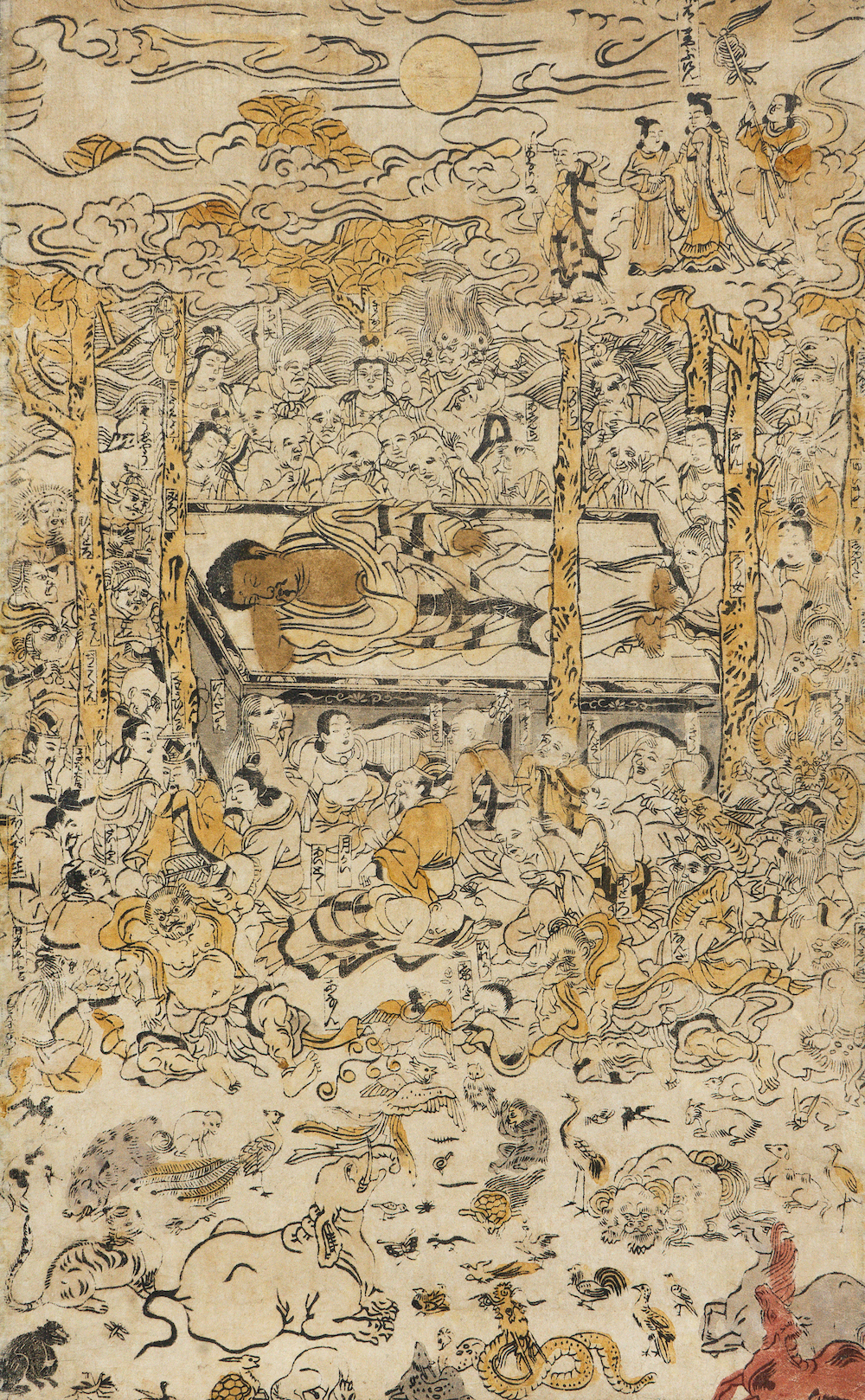

NISHIMURA SHIGENAGA (m. 1756), “Death of the historical Buddha (nehan-zu; sanskr. Parinirvâna)”. Edo, period 18th century

(Cover image: KÔ SÛKOKU (1730-1804), “Two acrobats and their rider.” Edo period, mid 18th century. All the images courtesy & ©: Sammlung Viktor & Marianne Langen)

María Inés Plaza Lazo is an editor, curator and strategist committed to dismantling capitalist hierarchies in art and communication. Born in Guayaquil, Ecuador, she operates between Berlin and the world, shaping frameworks for collective thinking and action. Trained as an art historian at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, she integrates critical theory and historical analysis into her practice. She co-founded Arts of the Working Class with Paul Sochacki, a street journal that confronts the intersections of poverty, wealth, art, and society. Edited with Amelie Jakubek, Dalia Maini, and a network of contributors, the journal amplifies voices across disciplines and languages while redistributing resources—vendors keep 100% of sales, making each issue a tool for survival and solidarity.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)