Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

It had been a while since I last walked through the immense, rambling campus of the Universidad Complutense of Madrid. The path I chose on the 18 February of this year was particularly eventful, and I reached the entrance of the Fine Art faculty almost an hour after the designated time to attend a mysterious encounter… and they were still waiting for me! They’d even called to see where we were, but unaccustomed to receiving so much attentionmy mobile had been left with no signal. A few days before I had heard talk of an intimate event being prepared in the faculty library. I’d not seen it on any social network, nor through any of the newsletters to which I’m subscribed, so much as I’d been told about it by Javier Curz, who was one of those invited to participate.

It was to do with Contadas obras, a project by Christian Fernández Mirón, organised along with Selina Blasco and Javier Pérez Iglesias that consisted fundamentally in the explaining of pieces. The narrations were quite disparate: the guests took it in turns to recount personal experiences from very distinct positions, that included art works, literary pieces, everyday accounts…in a cosy, storybook atmosphere that suggested a small voyage in time.

The conditions, in which this idea materialised, that I’d heard about a while before and of which I had consequently construed a mental image, surpassed my expectations, even though they were high. One of the rules of behaviour that the experiment required was the avoidance of any photographic or audio-visual record, thereby eliminating its possible automatic or subsequent broadcast. I’m very interested in the many communications linked to the Internet and mobile devices, but I’m not keen on live retransmission on social networks. I don’t seek the consecration of actions or events, but I can’t avoid the fact that mobile phones raised in the air to take photographs are a turn off. To return to Contadas obras, this condition, granted for me (and I imagine for the rest of the internet-dependents) a therapeutic character to the matter. In “Art Workers: Between Utopian and the Archive”, Boris Groys deals with some of the current conditions of artistic work derived from the use of the Internet. He indicates that “the process of art production insofar as it involves the use of the Internet is always already exposed – from its beginning to its end”: an exposure that leads to the constant documentation of the processes of production, expectation and participation in many projects. If the obsession to archive every activity, every event, generates a sort of “universal spectator” and a constant surveillance of the work and its results that we offer voluntarily, Groys calls for “the dynschronization of the time of work from the time of exposure of its results”, understanding that it is here where the creative work takes place. Creativity is a very broad concept and takes places in many distinct contexts; however, I do think it is interesting to extrapolate this idea of the processes of participation and expectation of an art piece, particularly when dealing with the performative. This desynchronization between the experience and the record favours the experience and generates more complex and powerful narratives than the immediate images and texts that populate the profiles of Facebook, Twitter and many websites.

In the first pages of Molloy, between digressions and promises that the plot is about to begin, Samuel Beckett writes, “What I need now is stories. It took me a long time to know that”. When I entered into the exhibition dedicated this spring to Jeremy Deller at the CA2M, I felt the same as Molloy. The piece that opened the exhibition, at least in the route that I took, was Beyond The White Walls, a series of slides commented by Deller that brought together images of performance and/or ephemeral pieces realised between 1997 and 2012. A narrative that opens up the doors to his work, to the pieces that don’t fit in to the exhibition format but also to the processes that don’t enter into, nor need to, the results of those that are exhibited. It’s taken me a while to know it, but this orality that drives the narrative dimensions of artistic projects has its place and is the most attractive thing I can find in an exhibition proposal.

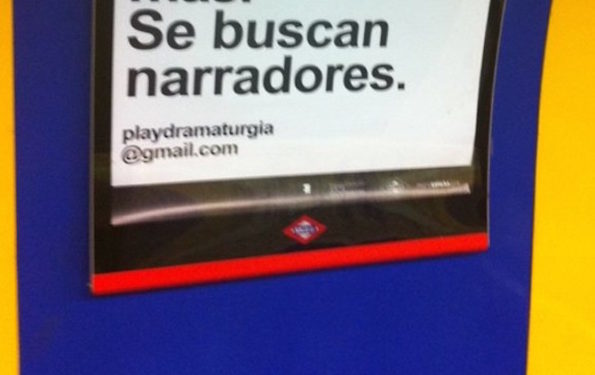

I’ll tell you something more. At the beginning of this summer some posters appeared in advertising slots in the metro of Madrid, with a simple design that explained: “This poster betrays the project, we’re not going to print one more text. Narrators sought” and alongside the email of the collective Play Dramaturgia. They were the first indicators of DIXIT, a project framed within the programme PHEstudios: Imatge no disponible, curated by Emilia García-Romeu and Selina Blasco for PHotoEspaña15.

In this edition of the photography festival, the Play worked around experience and narration in La Venencia, a vintage bar in the centre of the city where it’s not permitted to take photographs. It is a classic scenario for the experiences that form the collection of stories of the bar’s regulars, but also a place par excellence for everyday and extraordinary narratives. After that first brief open call, on 18 June on the collective’s Facebook profile, a mobile phone number appearedin large blue letters on a yellow background explaining: “Yesterday was the first action of DIXIT. If you want to know what happened, call this number on Friday morning from 13.00 to 15.00”. I noted it down. On the following day at 3pm I called, at the last minute, thinking that maybe the line would already be disconnected. My interlocutor was not very strict and began to recount a crazy evening that began with a talk by Jaime Conde-Salazar in the Museo Reina Sofía and ended in a rowdy part in a 24 hour church, in the calle Hortaleza, which he recommended I visit. I thanked him, we bid our farewells, and I hung up. In the following hours I had to reconstruct the story a couple of times to several people who had not managed to call and each time it sounded stranger and more ludicrous, as it didn’t seem to establish any relation between what appeared to be a cat curled up on a stool and the forebear of the person who entered into a church on horseback.

I listened to this story once again a couple of days later in La Venencia, convened for a couple of glasses of wine within the itinerary of the programme. There I discovered that the image I had constructed of the narrator with whom I had talked was not real. It wasn’t a direct testimony, so much as in this first transmission they were working on the figure of the interpreter of the narrative. In the following phases of the project other chroniclers, taxi drivers, hairdressers and masseurs also appeared. The chain of narrators amplified exponentially, retracing the forms of orality in an uncontrollable space-time. It’s great to imagine that 17 years from now someone might hail a taxi and on getting in ask what happened in La Venencia on that afternoon in June 2015. In this way, Play Dramaturgia fights against the bad luck that Walter Benjamin identifies in “The Storyteller”, about the falling value of experience and narrative after the Second World War, seeking the distance and the suitable viewpoint from where to generate narratives out of the creation and exchange of experiences.

Contades obres and DIXIT stem from the awareness of the relevance of the present and experience. They are exercises in the possibilities of narration in relation to the context of the production and transmission of artistic creations. They investigate structures and methods of contact and communication in the performative, beyond the assimilation of the usual parameters of mainstream media and those generalised and limited by the corporate services that operate in the Internet. This vindication of narration is perhaps a liberating impulse for the conditions of production and reception for art works, at least for those of a profile of the precarious-self-employed-male/female-orchestra, widely extended in these parts. They are exercises that propose scenarios in which to make more flexible and extend the forms of reception and participation in artistic processes overly influenced by contemporary systems of communication. Faced with the recording and direct diffusion of creative processes, these projects wager for conscious, careful, and experimental construction of polyphonic narratives. In the face of the spectacle of unlimited virtual armchairs, they create intimate scenarios, closer to a bar than a window display.

Dedicates her time to curating, teaching and empirical investigation, moving from project to project, without ever being very clear about the frontiers that divide them. A precarious existence, that stresses her out, but every now and again she allows herself the luxury of a mid-week siesta.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)