Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

A fourhanded epilogue [[those of Oscar Guayabero (OG) and Joan Minguet (JM)]]

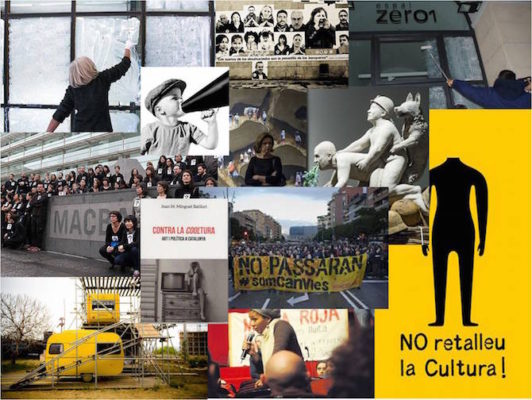

OG: Since the editorial Els Llums made reality, in the form of a book, a compilation of the articles, posts and interviews by Joan M. Minguet Batllori under the title “Contra la Cooltura“, the author hasn’t stopped appearing in the media. Obviously not during prime-time television nor in the traffic lights of La Vanguardia, but if we bear in mind the little repercussion that books have in the press, and even more so if we’re talking about art criticism, it could be said that Minguet Batllori has got lucky. The problem is that having read so many interviews I’ve lost interest in interviewing him myself. Whoever wants to read them has simply to look online or in his Facebook profile. So in order to respond to A*Desk we’ve decided to do something different, not just to be eccentric, something I’m already keen on, so much as to try and contribute a new gaze that we’ve maybe not had until now.

I begin the epilogue, proposing an exercise in self-criticism. Referring to a programme on TV3, in the book it says that it would be absurd to think that artists, curators, and art critics endeavour to make their creations, exhibition discourses, or texts hermetic pieces that are inaccessible to the public. I’d wager nothing on that. I’ve left many exhibitions or finished reading texts with the sensation that they had been created specifically so that I couldn’t comprehend them. The distance between endogamic discourses stuffed full of meta-texts and self-references and the public can’t just be by chance. If it were we’d have to talk about error. I believe that the cryptic spirit of many exhibitions forms part of a way of understanding art. I totally agree that the culture I’m interested in is one that demands a bit of effort, but you have to give clues, create links, generate non-didactic but yes comprehensible narratives. Now then, this is riskier, if the generic, not the faithful and supporting, public understands the proposals and it’s possible for them to have an opinion, it’s even possible they could criticise and place in doubt some aspects of what they see. Is it not then that this distance between the public and the discourse is a self-protecting defence mechanism? If we take this as our hypothesis the analysis of the art scene would change, the high-handedness would be nothing more than a symptom of weakness and stage fright.

JM: But how do you find the balance between “making yourself understood” and saying interesting things, which require some effort on the behalf of everybody? Because it’s a question of balance, of finding ways to make your work enter society, of being transparent or understandable, but without falling into the blockbuster and alienating entertainment. In reality, within what comprehends culture today there are some demagogic stances: an exhibition of contemporary art has to endeavour to be understood by a major part of the general public, agreed, but we can’t lose sight of the fact that the phenomenon of the “museum as spectacle”, of museums full of visitors, is new a product of the very society of spectacle diagnosed by Debord. How many of those visitors enter the museum to learn something, to really look and not just glance, how many are even minimally prepared to know what they might find? An exhibition, however understandable it may be, is a complex, intellectual artefact, constructed on the basis of a mechanism that is part visual part intellectual pathway. And all of this can’t be digested like a game of football. It calls for a certain predisposition, for some effort. Having made this effort it may be you come to the conclusion that what’s on offer is too impenetrable, made by a bunch of arrogant people, but from the outset we ought to know that there is a type of culture that isn’t made for all publics and this is an absolute entelechy.

OG: It’s a complex question. When Guy Debord condemned the society of spectacle he did so with the intention, perhaps naïvely, of dragging culture from its natural, closed, opaque ambit into the rest of society. For him art was transgression and the power of this disruption (a word I know you like) needs to expand its actions beyond the Museum, beyond the “cultural environment”. This has nothing to do with trivialization by television. Could we talk of trivialization by way of a self-indulgent endogamy? That is to say, cultural projects that only reach complicit circles that satisfy the ego of those who make them and who at the same time will be a devoted public to the following project made by someone in their circle. I know the discourse is schemingly tendentious but in this way one could understand the disappearance of art criticism, beyond the frivolity of the cultural section of the newspapers in the format “culture and spectacle”. That is to say the “cool” could also define the “trends” of the sector itself. It seems to go in fits and starts, now it’s political art, now it’s the turn of the culture of the archive, now it’s the turn of social mediators, etc. But in many cases, I’m not saying in all, fortunately, they are just exercises in internal consumption with no capacity to shake up reality, as Debord wanted. For example in that insistence on exhibitions of the archive in the end you saw the exhibition display simply eat the content. There was no intention that anybody use this archive as a working tool to generate alternatives, it was simply a dramatization of the archive. When it’s about social mediators you often see, I repeat not always, the social conflict being dealt with ends up as an excuse, once again, to present “sensitive” material. It doesn’t penetrate into the reality; it just takes note and aestheticizes it, turning it into artistic material for the benefit of artists, curators and loyal critics.

JM: Let’s be clear: the cultural sector, the sector of visual arts as an integral part of culture, ought to find ways of permanently thinking and rethinking itself, I’ve alluded more than once to the need for self-criticism. There’s an urgent need for a thump on the table so that it’s not just a few who decide on everything for the sector, to eliminate this silence (silence is always an accomplice of the system) that the people of theatre, literature, the arts and thought have maintained during times of overwhelming social tension. And all things considered, I don’t think that the concept “cool” is what would dominate our field of work. It’s not us that wants to eliminate thought, dissidence or art criticism …Look, criticism is practiced more than ever, as James Elkins says, because it has reinvented itself after journalism took away its traditional platforms leaving its pages with intentionally neutral information. What I mean, in case I’ve not made myself clear, is that you are right that sometimes the contemporary art museum takes social reality, conflict and “limits itself” to verifying it, or as you say aestheticizing it. Nevertheless isn’t that its mission? Can art do anything other than make up discourses, stories and thoughts about society? The outcry against injustice and inequality of our society is developed in the street and there the artist, the curator, the thinker, and yes also the designer, can carry out actions. But when all this reaches the museum its left neutralised, as Adorno said. Not so long ago, there was that political action by Josephine Witt against Mario Draghi: to me it feels like a performance, an artistic action of extremely high ideological content, it’s a shout loud and clear. But I fear that it won’t be long before, legitimately and with a desire to transform things, some artist takes those images of the action, intervenes in them in some form (aestheticizes them as you put it) and presents them in a museum in such a way that the real outcry against the system is left neutralized; it will be nothing more and nothing less than representation. And what’s more, as Rancière says, when the spectators of the future see it, only a few spectators previously aware of the social inequalities will understand the reasons behind the piece. The rest will just see a pretty girl throwing confetti at a startled gentleman.

OG: This is why I believe the presence, of intellectuals, artists, and creators, is so important in the social networks. I’m surprised that apart from a few exceptions the majority of visual creators use the different social networks like any old user, a little bit of self-promotion, a few common places condemning the system, the odd gentle contretemps with someone in the field, a few personal traits and nothing more. Is there no research? Is there no desire to transgress the medium itself? In this sense your position to me seems interesting. You enter the web to “fish”. You catch high-speed readers of tweets and posts and redirect them to your blog where you propose texts that call for a more deliberated reading. This change of reading pace to me seems like a provocation. Your way of producing interference in the trend of superficial speed is to capture readers for posts that need reflection, pauses or silence. A good way of hacking the traditional media, the vertical and unidirectional structures (from top to bottom) that occupy the book to a great extent for their power to trivialize, would be to generate horizontal networks. These networks where the node of Jeff Koons is as important as mine, and a post by Noam Chomsky can generate as much debate as mine, could even out the balance in respect of the transmission of information, analysis and cultural discourse. Lamentably, I don’t see artists, curators and critics up for this task. It’s as if they still don’t believe in their potential and use it like teenagers, just to chat. It reminds me of the beginning of television, art turned its back on it, considering it low culture and left it in the hands of programmers and advertisers. And that’s the way things have gone.

JM: Not so long ago, leaving the presentation Vicenç Altaió and I had done of the book, you told me about this hypothesis of yours, that I was a fishing the net to carry people to a place where reflection could go at a slower pace. I’m not sure if it’s true, but thanks for the distinction: I’m the fisherman. Jokes aside, it’s true that I’ve found myself in the midst of controversies in twitter where I’ve found it impossible to continue. You can state your opinion in one hundred and forty characters, but you can’t defend it. In Facebook it’s different, I have read interesting debates there, but suddenly someone appears who makes a joke or puts something tangential and the discussion gets diverted. But blogs are also social networks and the interesting thing is playing with all of them, also with those that are just visual. Some devices serve for some things, others for others, but what’s interesting is that they are all connected and logically also to reality. It’s what the traditional media and the society they represent, the analogue society, haven’t understood or don’t know how to resolve. One example: those of us of a certain age, who come from this society of the ancien régime, often talk about the impact of a newspaper editorial, the stance of an entire medium in specific subjects (political, social, cultural…) but this is just a mirage. Young people will only know about those positions of power that reach the networks and if they get there it will be through the eyes of the citizen. Journalists like Josep Cuní or Pilar Rahola think they have a huge influence, the ancient, “analogue” politicians, pay attention to them but it’s all a lie, their influence on the population is today almost null and void. It’s fantastic! A Copernican twist that’s also occurring in the university: in the classrooms we now don’t have to impart information (it’s the death of positivism, and it was time!), we can dedicate ourselves directly to the transmission of knowledge, to promoting a critical spirit. But it’s logical that many residues of the analogue society still remain, this all happened yesterday, the technological supports and devices change at breakneck speed. Nevertheless perhaps you are right that the art world is taking too long to adapt to this new world. The thing is maybe it’s not that there is no investigation, as you ask, so much as research requires time that isn’t contemplated by this digital society. In the exhibition “Species of spaces” that Fede Montornés has presented in MACBA, there’s a really interesting piece by Serafín Alvárez who has made a sort of computer game, where the user moves by way of a mouse through an infinite series of corridors; what before in a painting would be the spaces of Escher, painted or drawn, now enters the museum in digital format. In short, could it not be that we ask for speed and immediate answers of a sector that works, we work, above all with time?

OG: So, what would be desirable is that after your criticism, undoubtedly necessary, sooner or later we could write a book that maps a new paradigm for the role of politics and the media towards art and culture. In which the artists use, parasite and subvert the digital media (a “Let’s occupy the surf” of the internet) without forgetting to occupy MACBA to call for a new mode of functioning, not just a new director, to whom incidentally I wish all the luck in the world. We are in a moment of change, we don’t know what will come but we do want to avoid it being a continuation of what we have, the professionals of culture, not cultural figures, have to involve themselves fully in the role of a public function and relation with culture. As you so rightly say in the book, CoNCA was a good tool, now dissipated and converted into an ornament. “Contra la Cooltura” offers a good photograph of the current scene, and it’s undoubtedly disheartening, but now it’s time to work to modify it.

JM: : I’ll sign up for your desiderata: not so many years ago Barcelona was, culturally, a raging nucleus. It’s now up to us to stir up the fire, the coals are still warm, but we need to give them a blast of air.

Oscar Guayabero (Oscar Martinez Puerta), was born in the Raval of Barcelona in 1968. He studies Art and Industrial Design at the Escola Massana in this city. His work develops between theory, criticism and analysis of design and architecture. He currently combines teaching in the area of sustainability and history of design and the image of various schools in Barcelona, with external advice on communication for Barcelona City Council and curatorial-exhibition projects.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)