Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

“Abolition is not absence, it is presence. What the world will become already exists in fragments and pieces, experiments and possibilities. So those who feel in their gut deep anxiety that abolition means knock it all down, scorch the earth and start something new, let that go. Abolition is building the future from the present, in all of the ways we can.” Ruth Wilson Gilmore

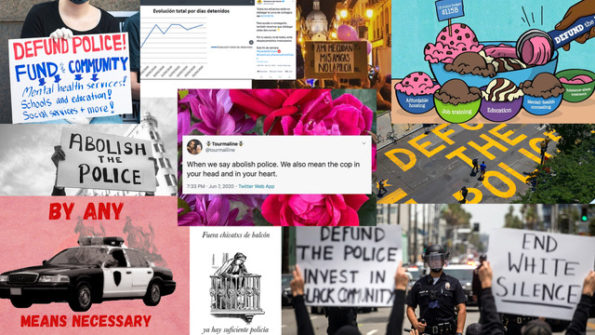

During the wave of protests against police violence and institutional racism that swept across the United States in the summer of 2020, a change of message could be seen. Protesters no longer carried signs with just Black Lives Matter or other anti-racist slogans, but also “Defund the Police” and “Abolish the Police.” What does this change in the grammar of protest imply? Is it a strategic change in the fight against racial capitalism, a shift towards an already operational horizon? I would like to take the time to look at this complex image in order to analyze its profound, almost seismic implications.

What these slogans point to is «one of the best-kept secrects in modern life. Experts know it, the police know it, but the public doesn’t know it».Namely, that the police are not here to guarantee citizen safety. Various experiments and studies (for example, one carried out in Kansas City in 1973) have repeatedly shown that police presence does not reduce criminal activity nor the perception of risk by citizens. Its sole purpose is to maintain social order by containing (not resolving) resistance to that order. It has had no other role since its origins, which are, by the way, colonial and industrial. These origins are to be found in the Irish Guard established by the British Crown to control the island, the London Metropolitan Police that were created to suppress the Luddite revolts, or the vigilante forces created to prevent slaves from escaping from plantations in the United States. In short: police emerged as part of the State’s reason to manage and exploit inequality in the 19th century, moving from repressive, expensive and cruel military techniques to new techniques of stable and legitimate social control. This is not the place and I am not the right person to explain in detail the causes and reasons for all this. There are dozens of recent articles and publications that have dealt with this issue, and they all agree that there is no reason to believe that a reform of the police force will bring about any substantial change beyond a little public facelift.

Which is why we can sum up by saying that the police are an obsolete and violent institution whose time should come to an end. What, exactly, does the abolition or dissolution of the police mean? The proposal is to redistribute of the funding destined to law enforcement agencies between social and community services, such as, for example, housing, education, employment and public health, all of which have a direct impact on criminality. More and better social facilities translate into safer communities and lower crime rates.

On the other hand, what these studies also show is that the police are much more than a group of uniformed men. They are, above all, a control mechanism that has been reinforced in the recent decades of neoliberal government, and which has normalized the culture of (in)security, surveillance and fear as a complement to social fragmentation. The result of this is the current reformist climate, focused on promoting a renewed image of the police in terms of diversity (both gender and ethnic), professionalization (with extensive training programs and regulatory bodies), proximity (with the creation of community police) and prevention (rather than repression). In other words, a (successful) effort has been made “to socialize the police and police the social.” As Sergio García García and Débora Ávila Cantos so masterfully explain (complete with large doses of terror), this has taken place in the Spanish State through the abandonment of social policies, replaced in part by emergency management programs and corporate civil liability projects. This gap has been exploited to allow for the infiltration of the police into the field of social intervention and, with it, the internalization of surveillance both at a personal and neighborhood level. Thus, in recent times, we have seen and experienced firsthand how the police assume the functions of social workers (mediation of neighborhood conflicts, presence in schools through talks, revitalization of citizen resources, etc.), and, at the same time, we have seen how all of us have, little by little, become the police. From Left to Right, there has been a rise in semiotic police and “criminationalists“, the punishment mentality of “pissed off” neighborhood associations and, more recently, balcony vigilantes. We are living in a new era defined by policing in which the culture of police force and the maintenance of order has been installed in other -previously unimaginable- social, professional and existential spheres.

Coming back to the present moment, I believe that, at this point, no one is unaware of how the crisis unleashed by the management of the pandemic has resulted in a notable increase in the police presence in the streets. Along with this, there is also a notable increase in the policing of the public sphere and an increase in bellicose language, sanctions, appeals for discipline and for individual-collective responsibility, as well as moral injunctions on the street and in social networks… all of which results in a breeding ground for authoritarianism and its abuses, contrary to all forms of community development. Another of the major consequences is that the Covid virus has exposed and drastically exacerbated existing social, economic, and political inequalities (seen quite clearly, for example, in the possibility of millions of children taking online classes or in the polarization of wealth). This has also revealed, in a dramatic way, how the mortality of the virus has been greater in places where social infrastructure had become scarce or practically non-existent after years of austerity, racism, budget cuts, and political wars. Police and policing are not only contrary to community development, they also exacerbate the inequalities and grassroots problems that they supposedly address. It is worth quoting here, in light of what has already been said, two very pertinent questions posed by José María López-Riba: “Was the policing of the management of a (let’s not forget) health crisis really necessary? […] After all, isn’t it better to protect ourselves against the virus (with strong public services and community support) than to go to war with it?”

The beauty of the abolitionist philosophy lies in its vital, operationalist force. As Ruth Wilson Gilmore points out, abolitionism is not about complaints and compassion, but about politics rooted in life and death. It is a long-term practice based on presence, on being present and building from the present, and of how we connect and multiply the networks that have the capacity to give rise to (not to lead) a broad movement in favor of social justice, in favor of a livable life. As my friend Victor Aguado Machuca reminded me, abolitionism is not a utopia; rather it is our present that behaves as an anachronism. Abolitionism allows us to think and act in a systemic way towards community life, recognizing shared vulnerabilities and solidarity. And from there, it enables to join forces in the fight, to design and organize ways of operating against these vulnerabilities in a communal way, and to promote “projects that affirm life,” such as those proposed by the promoters of defunding the police. Thinking with and through this intersectional horizon also leads us to abolish not just one but “ all violent institutions,” including prisons, the workplace, the university, the professor, the curator, or the artist, as Moten and Harney suggest. They propose, in addition to abolitionism and presence, to add the concept of exodus: the ability to withdraw ourselves from the violent institutions and relationships in which we participate, to abandon en masse, instead of remaining in an antagonistic position, and to activate forms of radical complicity “in favor of the radical realization of presence.” That is, to abandon the institution of the artist, the curator (A.C.A.B. both for cops as for curators) and “their deep, stagnant waters,” as my dear Raisa Maudit suggests, in favor of a shared aesthetic and intellectual presence.

Recently, in a class we taught together, my colleague Hypatia Voulourmis reminded us that the Greek etymology of “apocalyptic” refers not only to its capacity for destruction, but also for revelation. She thus invoked apocalyptic feminisms whose revelatory forces would eventually undo and destroy heteropatriarchal and racist worlds, called to disappear, creating in their place other livableworlds. We could say that the image of de-policing that has arisen over time, thanks to the enduring legacies of abolitionist black thought and activism, is precisely that: an apocalyptic image, a seismic image or horizon that already contains the fragments and pieces of a world to come.

Julia Morandeira Arrizabalaga researches, writes, teaches, organizes, talks (sometimes a lot, sometimes in public), gossips, reads, reads more, conspires, dances, runs, mothers, cares, lazes, dresses up, argues (a lot), laughs, sings (badly, but she loves it).

Photo credit: Galerna

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)