Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

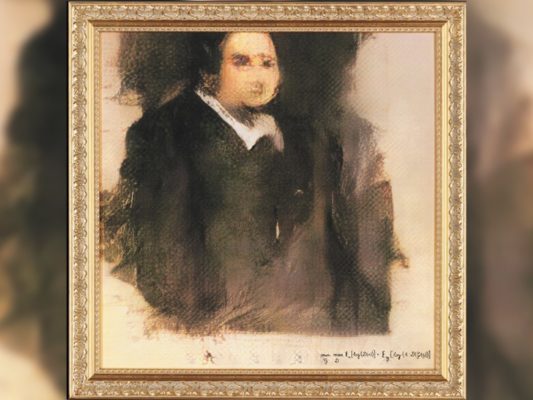

The Belamy family has no biography; all it has is a dozen ungainly portraits produced by a machine. Their history began to be well known when the Portrait of Edmond de Bellamy was sold by Christie’s for € 383,000, after having started out at € 7,000. The oil painting of Edmond – that on the day of the auction shared space with works by Warhol and Lichtenstein – is the last work in the Belamy saga, a series created through a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) algorithm by the French collective Obvious. The algorithm feeds on and learns from a database of over fifteen thousand canonical portraits produced between the fourteenth and twentieth centuries. Its programmers tried it out with landscapes but decided that ‘for the time being, portraiture is what best enables us to imitate creativity’.[1] The result is an oil painting printed on canvas and its corresponding golden frame to ‘produce a better impact on the collective imaginary’, signed in the lower right-hand corner with a part of the algorithmic code.

This is one of those news items that are perfect for drawing the attention of panellists who speak openly: those who snootily ask whether this is art; those who deliver sensationalist headlines like ‘Artificial Intelligence Reinvents Painting’; those who know-it-all and mention other artists as forerunners in the same field; those who are well-meaning and spend their time judging the qualities of the work; and even those who predict a low-cost future for art created entirely by machines. Apocalyptical and integrated authors who either see the future of artistic creation in machines or else see a simulacrum, a single pretence. Many of them, of course, don’t let the price the work fetched at auction go unheeded and are therefore condescending and show admiration, as if the mere whim of purchasers eager to have the latest and most brilliant novelty, even if it be a value judgement and a seal of approval. The market passing sentence, there you have it.

Beyond all these opinions on Edmond de Belamy (this is a case that can revive a languishing after-dinner conversation, just give it a try), the interest can presumably also be related to the vague fear and fascination produced by the binomial ‘artificial intelligence’ and, above all, to the parameters under which it has been created: how it has been ‘taught’ and what was the intention of the mad scientist who created the modern Frankenstein with an artistic sensitivity. We must continue to ask, because we’ve become increasingly less naïve (or so we think) regarding the wonders of the tools of artificial intelligence and the controversial problem of data mining that also enable us to control, trade, influence and spy. However, if we go by what is said in the Manifesto posted on the website of the Obvious collective, its objective is quite humble. Taking as an example an imaginary metaphor according to which a child, under the teachings of the right master, can end up creating Picassos, they arrive at the technical explanation that the algorithm is trained to discriminate any intention to move away from previous human models.

What could have become a thrilling story about the creation of a characteristic aesthetic identity starting from collective memory becomes a bureaucratic addition of components to reach the tedious common sense of merely statistic sums. No margin for error, improvisation or creativity. The deception doesn’t lie in whether it was able to replace human ability, or even whether it has questioned the art market, but rather in the fact that it is a mediocre impostor unable to move beyond standardised parameters. In short, a mere imitator plugged into electricity.

Human beings are still more entertaining when it comes to making up stories. At a very different level we have the example of an artist (a nearby, local case I have followed, on and off, with interest) who made a slightly late entrance in the art world but then went on to forge a career at a surprising speed. His stance is far removed from the romantic image of the artist locked away in his studio in search of his own voice, who suffers when he compares himself to his idols, leads a disorganised life and believes that his oeuvre speaks for itself. His is quite the opposite, as we find ourselves before someone who works fervently to make his existence known, to accumulate headlines and construct an attractive c.v. And the way of achieving it is centrifugating a five-minute YouTube tutorial and an abridged art history guide. While we come across great artists in theoretical movements delimited by historiography, he invents an ism of which he is the sole representative: figurative Mediterranean Surrealism (two meaningful adjectives). Given the importance of having works in the collections of key museums, nothing could be easier than to leave a CD with images of his works at the media centre of the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA), and voilà — we can say he is represented in the permanent collection! If we run out of ideas we can always resort to the infallible method of supportive causes; there are so many we could defend … Finally, once the press has grown accustomed to our artistic status, a journey can be used to send a communiqué – with a photograph taken in an art gallery, for instance – stating ‘The well-known representative of figurative Mediterranean Surrealism is currently in New York preparing his upcoming exhibition’. His list of newsworthy milestones is long and, to a certain degree, operative.

It’s a direct procedure (cheeky or astute, naïve or rude, according to whoever happens to be looking) that calls nothing into question and only takes advantage of familiar shortcuts, even if the strategy followed is distorted and built on four undigested concepts. Without underestimating its metaphorical capacity – indirectly, it ends up drawing attention to the weaknesses of today’s art ecosystem – it lacks some of the ingredients inherent in a good parody. All things considered, however, it’s an exemplary story in a sense that its leading player is probably unable to guess. It could be a case study or the object of an exhibition without the physical production of artworks — only the artist’s c.v. displayed in the gallery, documented with the string of news clippings, photographs and other forms of ‘recognition’. It would be the last step required to make it more interesting.

And while machines and human beings still appear just as they are, imposture in the art world still has really bad press. Suffice it to include these two concepts in the web’s search engine to discover a whole range of entries with opinion articles that strive to expose lies but, above all, intend to establish the limits of true art. If you do so – though I strongly advise against the idea – you’ll reach the common denominator of three or four experts who rouse the spirit of Marcel Duchamp, whom they consider the origin of all the catastrophes of today’s art, and a little further down you’ll come across the Mexican priestess of aesthetic correction (we won’t give her name, in order to avoid a flare-up). When all is said and done, simulacrum or imposture – with their ironic and playful overtones – could be a wonderful area for shaking up the academic inertia of pre-established identities. In the meantime, the Belamys have been unable to fabricate their c.v. and at best are the pale reflection of earlier biographical accounts.

[1] All declarations of intentions are taken from their website: www.obvious-art.com/

David Santaeulària is a cultural manager and a freelance curator, though the day before yesterday he was the director of an art centre (Espai ZER01) and, not long before then, of the Regional Museum of La Garrotxa. Living in Olot and developing all sorts of projects in the fields of cultural heritage and the visual arts have ended up giving him the vision of a peripheral observer who explores different environments and makes few foes. One last detail: he finds it hard to get on with people who don’t have a sense of humour.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)