Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Excited crowds smiling alongside dangling burnt feet. Huddled next to what singer Billie Holiday lamented to be strange fruit. About a century ago, lynching was a social jubilation. White inhabitants in small municipalities of the gallant American south anticipated and celebrated the matinee performance that is the suffocation of black necks. Twisted from thick tree branches, bodies and at times even their private parts were exhibited as public sculptures decomposing under the scorching heat. Lynching sequestered potential public unrest in impoverished cities and territories by exhibiting unrest to the public. Decomposed corpses make for strong social glue. Jesse Washington was one such case in point. While the First World War was ravaging Europe, a never ending and muted Civil War continued to devour the United States. Washington was charged with raping and murdering the wife of his boss, Lucy Fryer. Back then, just as much as right now, sentencing suspects to death was a central component of the Texas judicial system. Whites that received such a sentence were subject to private demise: taking a seat on electric chairs or receiving lethal injections in closed off and controlled environments. Black people were denied such secluded and dignified execution. Washington himself was to be made into an example. He was dragged out of the kangaroo court and chained around his neck. Paraded down the street, observers stabbed and mutilated him. Taking revenge on the pureness of the white race, locals pinned Washington down and castrated him. Before being made into a repulsive decoration for all to see, a bonfire grew momentum and Washington was then hurled to shriek inside its flames and burnt to an absolute crisp. By the time he was twisted in front of the Waco city hall, it was hard to discern what remained of him as human. Violence is that which turns someone into a something.

Turning black bodies charred was calibrated as much as it was carnal. Lynching others and parading them in public squares was seldom a spontaneous act. In fact, like all other communal celebrations, it was an organised and calculated matter composed of shrewd political intent –choreographed from start to finish. Prior to the presentation of Washington that drew at least ten thousand visitors, then Waco mayor John Dollins wanted to cut a political coupon on his torched behalf. The idea was simple. Mutilating Washington would act as his reelection campaign, and prove that Dollins is tough on crime. But doing so depended on visibility. Keen on making a moment of harm last forever, Dollins called upon local photographer Fred Gildersleeve to document the proceeding. While Dollins would gain political momentum from the upcoming evidence of harm, Gildersleeve would receive access to document all stages of the deranged mobbing from start to finish. Gildersleeve agreed, but still wanted to understand how he could turn a dime on behalf of the carcass. Understanding that the noosing of Washington would be a moment to remember, he decided to turn his negatives into postcards and present the corpse as a commodity. Gildersleeve acted upon an uncomfortable truth: within market societies, making something commercial renders it morally acceptable. Temporary exhibitions of assault were immortalised in his photographs. Backed by local stores and companies, participants in the lynching sent them to distant relatives and loved ones, sharing their wonderful spring afternoon gatherings. Just like Christmas cards, those images were bought and sold en masse as precious souvenirs. In one such postcard, a seared Washington appeared almost no different than the tree trunk next to him, and someone wrote to his mother that this was “the barbecue we had last night. My picture is to the left with a cross over it. Your son, Joe.” During a time period that most commoners could not afford to have their portraits taken due to high production costs, being documented next to the dead was proof of their existence. Lynchers elbowed each other in the hopes of being caught in the limelights. How close one was to the corpse signified their importance within the community. Making nobodies into celebrities, people relieved a sense of power and control; an ownership of whites over the African American other in their life and death. Thanks to mass produced photographs, state sanctioned murder became a means of communicating with the living.

Two elements are striking in those terrible photographic tableaux. For one, the basic principle of who is depicted as an uncontrollable barbarian is reversed. While the white mob covers the photographic scape as if those were a destructive swarm of hornets, the lynched individual is haloed and echoes medieval iconographies of a martyred saint. Second, that swarm is documented as excited and ecstatic. Delighted to take part in what one postcard described as a “token of a great day”. Due to their communal significance, this utter lack of shame stems from the fact that the postcards were never considered to be a threat, a potential source of persecution, or a possible foundation for litigation. Yet confident as the photographed were, their absolute sense of assurance was short-lived. Lynching, it should be noted, that horrendous act so easily attributed to former and darker historical periods, was made illegal in the United States just three years ago. But the publication of “obscene matter as well as its circulation in the mails” was a punishable offence since the late nineteenth century. And while most of polite society and the intelligentsia of that time snubbed the postcards as evidence of the backwardness endemic to the South, it was its victims that used the evidence of such crimes against their own culprits.

Looking at the postcards from the safer distance of New York, leading sociologist and founding member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, W. E. B. Du Bois was determined to flip the value of those postcards on their heads. Rather than conceal the images out of concern for public distress, Du Bois chose to publish them on different terms and reappropriate them. Two decades after the lynching of Jesse Washington, another black man by the name of Rubin Stacy was abused and hung. His defacing too was turned into a postcard. Yet another memento mori, one that included Stacy flung on a tree, surrounded by white children and their parents. Du Bois and other leading black figures then published a pamphlet with that exact postcard. Remaking trauma as evidence, Du Bois and others commanded readers to “not look at the Negro”, as his “earthly problems are ended”. Instead, those concerned with such distressing images should “look at the seven WHITE (sic) children who gaze at this gruesome spectacle”. For example, is it “horror or gloating on the face of the neatly dressed seven-year-old girl on the right?” And is the “tiny four-year-old on the left old enough, one wonders, to comprehend the barbarism her elders have perpetrated?” Not just the white children are to blame. “The Negro was powerless in the hands of the law, but the law was just as powerless to protect him.” Not long thereafter, the nationwide circulation of the images set the lynchers into a mode of panic. Photographers such as Gildersleeve began corrupting all evidence of the events in question.

Thanks to the entertaining presence of cameras, framing a violent event as a public performance makes its audience feel less responsible for it. What Du Bois teaches us is that back then as much as now, relocating the spectacle of violence from a moral discourse into a legal framework is a complex but crucial step. Today, organisations such as the Hind Rajab Foundation and the International Criminal Court follow the footsteps of Du Bois. In using images uploaded by Israeli soldiers within the bellows of the West Bank and Gaza as evidence of crime, visual activists and legal scholars are able to persecute the culprits using the little scraps that remain of international law. Like the hellhounds from Dixieland, certain Israeli soldiers who were chastated for their actions deleted their social media profiles with great haste. Pride transformed into shame. When documenters begin to be documented, the arc of the moral universe begins to bend ever so slightly.

(Featured image: Cropped image of the postcard of the lynching of Rubin Stacey, Fort Lauderdale Florida, July 19, 1935)

Over the month, Bodies of Evidence has unfolded through five chapters:

First: Ways of Unseeing

Second: Trading Cards With Lives

Third: Performative Rape

Fourth: Gaze Deprivation

Fifth (this one): Evidence of Bodies

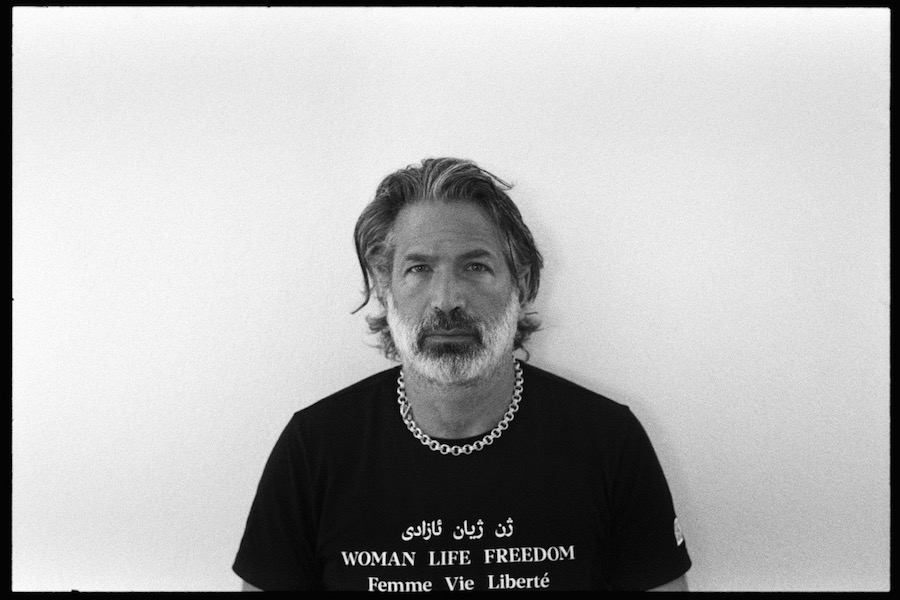

Adam Broomberg (b. 1970, Johannesburg) is an artist, activist and educator. He currently lives and works in Berlin. He is professor of Photography at Istituto Superiore per le Industrie Artistiche (ISIA) di Urbino and Practice supervisor on the MA in Photography & Society at The Royal Academy of Art (KABK), The Hague. His most recent work “Anchor in the Landscape” a large-format photographic survey of olive trees in Occupied Palestine was published by MACK books and exhibited at the 60th edition of La Biennale di Venezia.

Ido Nahari is a writer and researcher currently pursuing his doctorate in sociology. Previously an editor for the street newspaper Arts of the Working Class, his writing has appeared in numerous journals and magazines. He has lectured in various museums and academic institutions across the United States and Europe.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)