Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Among the finest reasonings of the neo-liberal and fascistoid extreme right we find pearls of wisdom that promote a vision of the world as a passive accumulation ready to be exploited. A voice that thunders in sewers and caverns with phrases like ‘they dress them like sluts’ or ‘I killed her because she was mine’, phrases that catch on in society and are sedimented in individuals, making them as hard as stones. This can be seen in the sexism and ignorance celebrated in reality shows, where disguised as young tattooed hipsters we come across the same old monsters of all times. Discourses designed to intoxicate, that resort to quotes by García Márquez or verses of the Qur’an to reaffirm, yet again, the alliance between men and power. A generalised opinion that sanctions harassing women, ridiculing creativity, imprisoning rappers, dynamiting Palmira, mistreating animals, contaminating food, running over strolling crowds, hitting old ladies, shooting schoolchildren and, of course, gang raping. A world of machos who must be constantly proving their manhood, a brawny competitiveness that at the gym, at home and at work is exerted with a pragmatic professionalism that shows signs of Anglo-American capitalism. Success recognised in the creation of traditional masculinities, the ambition of a shark on land, contempt for foreign truths and arrogance towards everyone. Moreover, all forms of success are based on the demonstration of this domination, physical or conceptual, that is revealed in urban segregation, interior design, interpersonal gesticulation, the use of language and, in some advanced countries, sponsorship of art and culture. These are the limits that define a potent class and a way of disciplining the aspirational classes who hope that one day they too will share the circles of power.

This ongoing feeling of unease that characterises our delayed contemporaneity is partially due to the intricate nature of today’s crises in which colonialist patriarchy, that steers our minds and customs, that knows it is invincible and exerts the power of fear, plays a decisive role. This mentality, which has shaped the world and controlled its resources, is a new geological epoch and is present in the cabinets of global governance. Over and above the Temers, Erdogans, Putins, Trumps, Dutertes, Modis, Xis, Zumas, Orbáns and Netanyahus, this is a globalisation that takes advantage of the anxiety it creates to organise an authoritarian reaction that traps and isolates citizens in unemployment, poverty, immigration and social failure. In this sense, Spain is a laboratory. Our macho alpha teaches democratic lessons without having been voted, corruption is accepted as an operative model, pensions vanish, the victims of male chauvinism are caricatured, and freedom of expression is trampled on while the official left obeys the will of the powers that be. A triggering of sensitivities or an alter-globalist goodness are insufficient to challenge these facts, for thy do not create programmes for the global society and are therefore insufficient for a change of paradigm.

Three recent examples trace new perspectives on feminism:

From the intersection with accelerationism emerged xenofeminism, which tries to take advantage of alienation as a revulsive space, emphasising the trans as an intermediate stage that avoids becoming enclosed in identities and looks for a global mobilisation. Among its proposals we find abolishing gender, as a ‘way of outlining the ambition of building a society where the traits that are currently grouped into the category of gender no longer form a network for the asymmetrical operation of power’. XF extends intersectionality to include technology and focuses on new forms of reproduction as a way of challenging natural determinism, along the lines of Haraway and Preciado. This spring shall see the publication of Helen Hester’s book, so we shall have more material on the subject. The legacy of cyberfeminism is included in the accelerationism of the left, highlighting the importance of the revolt of domination apparatuses and the recognition of a horizontal organisation, capable of being effective without a hierarchy.

In its turn, object-oriented feminism is a criticism of the distinguished group of men who have developed a theory based on objects as robust and indifferent bodies. In her contribution to the book edited by Katherine Behar (2016), Elizabeth A. Povinelli surveys Harman and Meillassoux in her effort to isolate objects from their entanglements and thus deflect social and political conditions. The veil that covered the reactionary nature of speculative realism drops and shows how a philosophy that prioritises objects did not contemplate those who have traditionally been considered objects and subjects of male power. An oblique example could be that of the Afro-American dominatrix who obliges her customers to read black feminism treatises in order to understand what it’s like to be an object dominated not by another person, but by a whole system.

The third instance is the new book by Jack Halberstam (2018) that examines the disharmony between trans activism and feminism and explores the possibility of a coalition to curb the male chauvinism that is re-emerging in the United States. Focusing on transitional ways of life, Halberstam opens the door to a future relational space. The body like a Lego architecture that doesn’t define identities; on the contrary, it carries out a continuous experimentation with life, development and contact with others. Instead of architecture that isolates, we need a flow between organisms that can create groupings and coalitions, a queer architecture capable of inspiring and generating lives in transformation.

These thoughts evaluate feminism, not only as a discourse sensitive to inequalities, but as a practice that connects struggles and fields of action. From the ecological crisis to vital precariousness, the male capital threatens and conditions the collective future. As we learn from Sadie Plant, ‘patriarchy is the precondition of all other forms of ownership and control, the model of every exercise of power, and the basis of all subjection’. We are fully aware that all emancipation processes involve a total change in power relations, between human beings, species and machines. The radicalness of the proposals is based on the conception of network and assemblage that reinforces a community space which is transversal and open to constant total change.

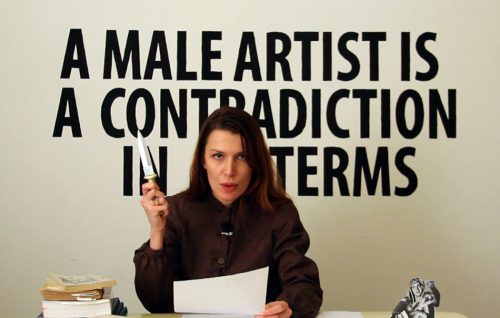

There are examples in contemporary art that aspire to interfere with the mechanisms of power. In their practice, artists mobilise, formulate, explore and investigate ways of subverting, nourishing, conditioning, experimenting, exercising a space of possibility, change, difference and transition that proposes, questions, incorporates, dialogues with audiences to make them think, project or activate specific experiential coordinates. Contemporary art constituted as a conceptual-aesthetic regime of praise of indeterminacy and social practice, but also much of the work based on the body, gender and a criticism of power structures. Suhail Malik, Armen Avanessian and Tirdad Zolghadr have called into question the effectiveness of this regime that was treated merely as content in the hands of the same powers it was supposed to disobey. Artists are objects, used and made profitable as creators of trends and horizons; this isn’t necessarily bad if that’s their intention although it does entail certain doubts when the creators try to undermine the mentality of domination.

Only in laboratories like Spain do we find people outraged by a statue of Franco placed in a fridge or the pictures of political prisoners on display at ARCO. Such a reaction only proves how claustrophobic the atmosphere is and reveals the lack of connection between art and society. Is there anyone unrelated to the art world that remembers the Spanish pavilion created by Santiago Sierra for the 2003 Venice Biennale? During Aznar’s rule, the pavilion was closed to all those who weren’t Spanish nationals. The commotion that would be caused today by such a proposal is unimaginable. This case shows us, much to our regret, the scarce repercussion of such proposals and how quickly people forget them despite having been the talk of the town for a few days — in other words, the role exerted by artists as social instigators. Artists in Spain (like all professionals in the sphere of culture, with the exception of civil servants) have a residual presence, childish and fragile, and are considered to be sensitive and feminine (yes, scornfully). This idea has taken shape over the years thanks to the culture of grants that reserves a submissive role for the arts and is deferential towards power and the phrases that remind us of the same line of argument: ‘This? My five-year-old daughter could do this’ (yes, daughter, scornfully).

Artists are invisible labourers, the precarious workers on the corner, those who are unable to work in international circles due to the lack of a coherent foreign cultural policy exterior, those who depend on grants and earn their living elsewhere. It is a situation is designed to pauperise creators, remove them from the list of professionals that count, and turn them into objects, tokens on the board of a game played by politicians and subordinates who, in turn, make themselves out to be genuine great artists. This translates into the lurid scenes of Pujol telling the history of Catalan art in the documentary on MACBA, and Fraga designing the City of Culture in Santiago, and into so many other cases of overspending in the name of art and culture that in essence were really monuments to the megalomania of a handful of machos.

As against all this, we can’t go on thinking that the same old trendy practices will reposition artists as agents of transformation. Although not all artists find themselves in this quandary, those who do want to exert an influence and challenge the schemes of power face the necessary questions of how to be effectively dissident and what to do.

Xavier Acarín is fascinated with experience as the driving force of contemporary culture. He has worked in art centres and cultural organizations both in Barcelona and New York, focussing in particular on performance and installation.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)