Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

The Philippe Parreno exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris constitutes a great opportunity to enter into the world of this French artist, key to understanding contemporary art of the nineties. Anywhere, Anywhere Out of the World is the title of a show that reactivates the idea of the exhibition as a medium in itself. To the rhythm of Petrushka by Stravinski, the spectator has to wander through an orchestrated path thinking at the same time as much about the particular pieces as the whole disposition.

On the outside, the Palais de Tokyo begins with one of his famous marquees, or canopies of lights that announce the entrance, indicating to the spectator that it is situated underneath. The spectator is, from that point on, a self-conscious being that interacts with the experience that is offered to him. Once inside, another room contains all the marquees that the artist has made throughout his career. These switch on and off in a sonorous, robotic dance while the piano melody tinkles on in the background.

From the new, redesigned hall, the route through the exhibition offers all the different facets of this artist’s career; games, fiction and narration, the world of infancy, music, diverse collaborations and, for a short while now, also choreography and dance. All with the inestimable help of technology and a touch of the sci-fi. There exists here a certain weirdness, a blurring, at the same time as a contained and very subtle magnificence. 56 luminous signs (one for each movement of Petrushka) have been installed, indicating the way through. Suddenly, the signs flicker and the whole exhibition is immersed in this flickering. The usual labels indicating the works are small screens that also flicker on an off, transmitting messages in small flashes of text.

It’s not that easy, however, to understand the logic that governs this whole device. Only at the end of the visit does the visitor find the command room, the place where the central “computer” is housed, a room full of cables and machines. In front of this, a pianola, on to which ash falls, that automatically tinkles away (a piece by Liam Gillick) that introduces us to the ins and outs of this device as if it was a time machine. A gigantic metronome. Parreno thus remembers John Cage, who along with Merce Cunningham has a place reserved in this exhibition.

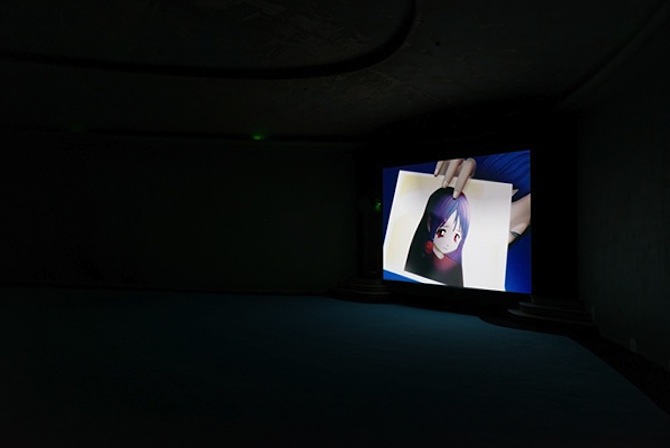

What is particularly remarkable is the spectral presence that reappears (like any good ghost) over and over again. The sounds of the troupe of Merce Cunningham on an empty dais; the spirit of Marilyn Monroe shut up in a hotel in New York; or the physical reincarnation of the Manga personality Annlee, the rights of which Parreno and Pierre Huyghe bought in 1999, and which here appears in flesh and blood, thanks to an adolescent in a work of the never indifferent Tino Sehgal. This constitutes one of the strangest and most magical moments that I have ever seen in an art exhibition. Occupying the entire space, Philippe Parreno executes a grand piece of “expanded choreography”, dance, architecture and also cinematography. This is the art of our time.

This and the simultaneous retrospective of Pierre Huyghe at the Centre Pompidou serve to feel the pulse of the by no means limited innovations within art institutions since the decade of the nineties. The sensation that one is left with after seeing them is of an absolute coincidence between the two artistic proposals with respect to their institutional frameworks. Today museums camouflage their ideological frameworks with art produced according to demand. Now any experience is possible, within the museum.

Michel Foucault defined the device as a network of relations that can be established between distinct heterogeneous elements that comprehends: discourses, institutions, architectural installations, administrative measures, scientific formulations, philosophical propositions, morals, etc. Though Foucault was talking about disciplinary devices, these have now mutated into the reproduction of a fiction of freedom and consumerism of liberalism. In 1995, Parreno, Huyghe and Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster founded L’Association des Temps Liberés with the conviction that it is more important to occupy times zones and reactivate so-called leisure time to do something productive, than the Situationists’ previous obsession with occupying physical spaces or spaces of resistance. Has time proved them right?

Peio Aguirre writes about art, film, music, theory, architecture and politics, amongst other subjects. The genres he works in are the essay and meta-commentary, a hybrid space that fuses disciplines on a higher level of interpretation. He also (occasionally) curates and performs other tasks. He writes on the blog “Crítica y metacomentario” (Criticism and metacommentary).

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)