Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

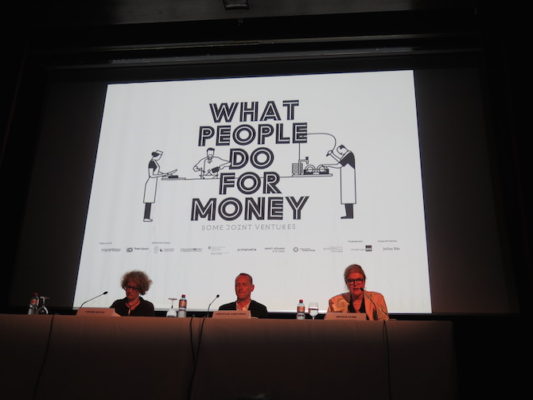

One day after the Manifesta opening Christian Jankowski was sitting on a little bench at the en-trance of the coffeehouse schwarzescafé in the Löwenbräukunst – which is one of the spaces for the Historical Exhibition of Manifesta 11. He gave one interview after the other. It was quite impressive how attentive he remained in every conversation – always committed, witty and appar-ently not at all distracted by the surrounding gastronomic hubbub. Jankowski, born in 1968, is a true performer and socialite, who in 25 years of artistic practice has become more and more in-volved in involving others, initiating, playing and switching roles. He lives and works in Berlin, teaching as a professor at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Stuttgart. Jankowski, therefore, seems to be quite a good choice for the 11th edition of Manifesta about “What people do for money”.

Are you satisfied with Manifesta 11 or do you have any form of hangover, as is often the case after organising such a big project?

All artists say in the end: this or that still has to be added or improved. In fact, I am very happy about what Manifesta 11 has now become. Although there are still some pieces I wasn’t able to include: for example, a 4000 year-old hairdresser made from clay from Egypt or casts from the Lascaux Caves. But I think that all of the thirty projects have turned out very well. And this is much more important to me. With regard to the number of participating artists, I imagine I could have invited three times as many. It would’ve been a fuller exhibition in an even fuller city—a spectacle, an incredible experience of parallelism.

So Manifesta 11 was intended to become a spectacle?

The term “spectacle” has a very superficial connotation initially, but it needn’t be superficial. I wanted to go for a different biennial format for a change. It was all about ways of presenting an event differently, about its visual appearance—that’s what a special effect does. Some call it a special effect others call it a miracle. In the case of this Manifesta, we are dealing with a multiple appearance artwork: thirty joint ventures, the collaborations between artists and professional representatives in three respective manifestations at three different sites. First, the collaborative piece shown at the hosts’ place of work, such as the fire station or police station, then at one of the Zurich institutions, such as Löwenbräukunst and Helmhaus—entering into a dialogue with artworks by artists from the fifties in the context of the “Historical Exhibition: Sites Under Construction” there. And finally in the so-called “Pavilion of Reflections” floating on Lake Zurich, in the form of films. These ART DOCS, as we call them, present all the joint ventures and can be viewed in the Pavilion’s open-air cinema at all times. Visitors, who have missed one or the other artwork at the above mentioned sites, will be able to catch the collaboration between artist and professionals in these ART DOCS.

What were the selection criteria for the participating artists?

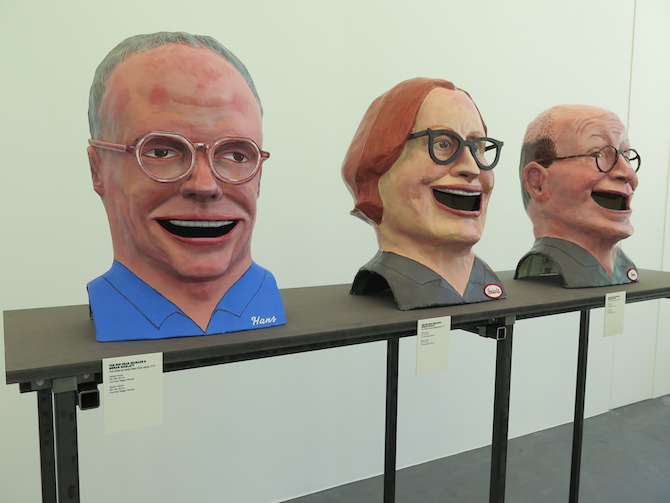

Mainly artists whom I found interesting during the twenty-five years I have been making art. Some are from my circle of close friends, such as John Arnold. I was immediately taken with his brilliant “Imbissy” idea with haute cuisine because “Imbissy” connotes “embassy” and of course takea-way/snack diner in German, which is a perfect match with a clean Switzerland as a country of po-litical and economic diplomacy. Through Arnold I met the Berlin Band “The/Das” who composed the Manifesta 11 song, or Big Brigade&Megan Marlatt, for example, who made those papier mâché heads depicting Hans Ulrich Obrist, Roberta Smith, and Jerry Satz. Another important selection criterion has been the inclusion of pioneers, such as Chris Burden, Guillaume Bijl, Susan Hiller, or Harun Farocki into the Historical Exhibitions, which I curated together with Francesca Gavin. Or my former professor, Franz Eherhard Walther, who was part of the joint ventures. If I had studied somewhere else it would have been somebody else and I never would have become curator of the Manifesta, for example. I cannot do anything but refer to my own life, my own standards of art and artists, which I find exciting. My attitude remains the same whether it says artist or curator on my forehead. Franz Ehrhard Walther plays a central role in my overall concept of art. I partially inherited the fun of playing with language and wit from Werner Büttner, who also taught in Hamburg at that time, when I was studying there with Stanley Brown, among others. In general, I was fascinated by the artists belonging to the Städel Circle, such as Martin Kippenberger, as well as by their predilection for irony and provocative images.

And then there are the discoveries—amongst whom are many of the younger generation who I didn’t even know about or only vaguely before the Manifesta. Fundamentally, the Manifesta was a fabulous opportunity to ask my artist and curator friends which studios in which cities I should visit. So I travelled a lot in 2015—together with my curatorial coordinator, Maria Isserlis.

Finally, there was the corrective action of my curatorial advisor, John Beewson, who was in charge of the lists and who discovered that “for a European Biennial, there are too many Germans, Amer-icans, and Mexicans!” This is because I`ve had a lot of shows in these countries. Suddenly, I real-ized that we needed more artists from Eastern Europe—bearing the motto “always maintain a balance!” One of the best trips for me was to Prague where I saw more than one brilliant exhibi-tion and met lots of really talented artists, many of whom are represented at Manifesta. But sometimes these parameters go a bit haywire, because shows like this aren’t worked out on a cal-culator. Whatever you do is going to be wrong and I freely admit: I haven’t invited as many wom-en as men, because it wasn’t the most important criterion for me.

The ART DOCS are based on a dogma approved of by Jean Luc Godard.

The dogma of the ART DOCS regulates the structure of the films, and the roles ascribed to the Art Detectives as guides and commentators of the joint ventures. It is about deconstructing the doc-umentation of art. I loved it when Jan Hoet presented documenta in his legendary marathon talks.

How important is the Cabaret Voltaire—the birthplace of the Dada movement – as one of Manifes-ta 11’s sites?

All the sites are equally important. The composition made up of the three manifestations of the joint ventures is of central significance for Manifesta 11. The spaces in the Historical Exhibition and the thematically-structured dialogues taking place there, form one pole so to speak, whereas the performances at the Cabaret Voltaire form the other—in the Here and Now and under the same conditions as the joint-venture artworks. This implies—in the Cabaret Voltaire—that everybody is a producer and then becomes a consumer of performances. No one can see a performance without having performed his own—together with a representative of a profession. Throughout the exhibition’s runtime, the Cabaret has been transformed into an artists’ guild, where creativity is the currency and not money. The role of the guild master is played by the Swiss artist Manuel Scheiwiller, who decides which performance will be staged. The attitude of “I am a consumer, I can buy whatever I want where I want” doesn’t cut it here in the artists’ guildhall. You have to participate in order to experience the Here and Now. The documentation is open to everybody: i.e., the drawings used to apply for a performance as well as the Polaroids taken of respective per-formances.

Was the list—presented to the artists beforehand, containing the names of about 300 Zurich resi-dents representing all kinds of professions prepared to enter into a joint venture with an artist—designed to be some form of cartographic survey of the Zurich working environment? Or was it more a matter of coincidence which professions were involved in the artistic process?

One doesn’t exclude the other. The artists chose the professions. One basic principle of all Mani-festa presentations thus far has been that the artists’ inspiration leads the way. And the relation between inspiration and coincidence is a complex one that isn’t governed by statistics. I also un-derstand “What the people do for money” on a different level to Jan Hoet’s Chambre D’amis exhi-bition format in Ghent. Private citizens offered their homes to the artists and their work in that context, whereas in Zurich, professionals offer their workplaces, their professional networks, and their know-how. You have to involve yourself in the joint venture. Of course, there were a few artists who were unable to enter into such a joint venture or collaborate with the Manifesta due to a different time constraints or even their wounded vanity. It’s a bit like participating in a Land Art show and then ultimately demanding a white wall or an air-conditioned space. For me, there wasn’t a specific psychological concept, which the artworks would effectively illustrate, because the ideology was intended to develop from one individual to the next within the process of crea-tion. So the personalities of the people involved in a joint venture was extremely decisive in all this.

Did you start off with a certain working concept—say, Karl Marx’s “Economy in its influential role” or Max Weber’s concept of “correlations/mechanisms of power, culture, and economy”?

My intention is not to illustrate any existing theory. I don’t want to dictate anything to the artists. They are free to make their own choices with regard to which joint venture they prefer. All possibilities are encoded in the encounters. This is much more complex and intelligent than a banner slogan, such as: “I will now open up a new perspective on ways of working in tomorrow’s world.”

Throughout the official opening at the University of Zurich, someone was distributing a leaflet in which Manifesta was criticized for its lack of art about work, such as “unpaid Care and Reproduction.” Another criticism was that Manifesta 11 used unpaid trainees rather than students as gallery attendants, depriving the latter of an opportunity to earn income.

As I already mentioned before: I am interested in art and not a sociogram of professions. That people have been exploited by the Manifesta is a very simplistic statement. We do not want people to lose their jobs. But such structures, like the support from trainees, are basic structures at all huge art events such as the documenta and the Venice Biennale. It is something like a Gesamtkun-stwerk or universal work of art, through which the gods of art are venerated. Those who have participated in such events are very proud when they can say later on that their work was part of the documenta and such like. And I would have loved to have talked to the author of the flyer, who goes by the pseudonym of Regina Pfister. She certainly achieved quite a lot. And actually it is a good thing as well that I managed to cause a few shockwaves in certain areas with Manifesta 11.

In the Süddeutsche Zeitung, Jörg Heiser asked whether the curators’ era has now finally come to an end. The US-artist collective DIS has curated this year’s edition of the Berlin Bienniale. Elmgreen&Dragset have been invited to curate the next Instanbul Bienniale. Are artists taking the curators’ jobs?

I don’t think so! How long has the word curator been in use? What was the professional term for the one who drew the first hunters and animals on the walls of Lascaux. Was he the curator? Did he paint or did he commission someone else to do the job? How many artists have already been curating up until now? When artists began organizing salons for their Berlin and Paris exhibitions, nobody was shouting: “The artists are taking the curators’ jobs!” I don’t believe in one or the other. I only believe in the coexistence of both. Of course, every artist can have another string to his bow and work as a curator. The same applies to curators. At any rate, in order to be successful as a curator you need a lot of courage, luck, and personality.

Uta M. Reindl, * 1951 in Cologne. Free-lance critic, curator, translator based in Cologne. Regular publications in magazines/dailies, mainly for Kunstforum International; catalogues; edition of two books – focussing also on contemporary art in Spain; curating joint-ventures of artists with students (1996 – 2010), art in public spaces (2001), in galleries (1999/2012); organizing the regional critic platform „Kritisches Rheinland“ since 1996.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)