Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

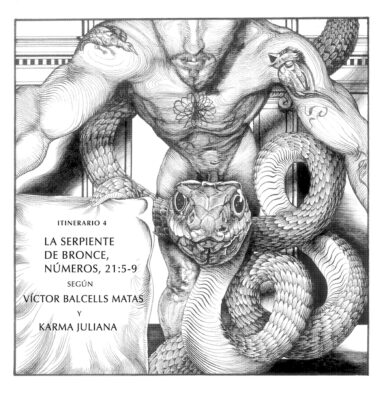

Marcel Rubio Juliana Dibuix anunciador 4

Marcel Rubio Juliana Dibuix anunciador 4We end in the same place where we began, with the gaze, although now it will be a different gaze, the deified or embodied gaze within the symbol of the serpent. Different painters have seen it and shown in it a valid proof of their art: a concept made for the occasion shows a polyphonic level of interpretation, which I will explain shortly. Sacha Esteban Buquet (@shura_xyx) guides us on this itinerary and as a spirit appears in the drawing in front of the temple that serves as a stage with a serpent wound around him, an attempt to shake up our gaze.

In this passage, I immediately thought of Víctor Balcells Matas, the only Spanish writer who could carry out an exegesis:

In one of her lectures, the Jungian psychoanalyst Marie-Louise Von Franz spoke of her experience with a famous German palm reader named Spier, author of several books on the subject. When reading hands he did not look directly at the palm but instead covered it with soot and then made an impression on paper. What he studied was the impression. Ella von Franz allowed Spier to give her a reading on the condition that he only look into her past, since she did not want to be conditioned in reference to the future. After reading her palm, Spier described very precise details of Von Franz’s life, such as the date and conditions of an important surgery. After the reading they chatted for a while and Spier explained that most of his power of divination came from his intuition as a medium. When someone came into his office he immediately knew many things about that person. The impression of the lines helped him to specify and determine things he already knew. Somehow, Von Franz explains, Spier was able to project his unconscious knowledge onto those lines and then pass the information to his client. This concept is related to the Jungian psychoanalytic principle according to which the unconscious has “absolute knowledge.” We have hints of this absolute knowledge through our dreams.

“The unconscious knows things; it knows the past and the future, it knows things about other people. All of us have dreams sometimes in which we are informed of the status of other people.” For Von Franz, a medium is a person who has a close relationship with that absolute knowledge of the unconscious. Generally, this knowledge is obtained when we are in states of reduced consciousness. We can follow this image of the medium in the figure of artists and in their creation.

We understand in the image of the snake that there are two forms or levels of vision (they are in fact a continuum, but to make ourselves understood we speak of two forms): one form is related to the accidents and avatars of existence, while the other rises above them in order to see the essence, and is thus saved. This way of looking is one of the keys for every potential artist, a skill that can be acquired and that is necessary to train given our natural disposition for consciousness and rationality.

If we look at traditional divination techniques, prior to the use of numbers, we observe that they are based on some kind of chaotic pattern from which the reading is performed. For example, reading coffee grounds, or in some African societies reading the bones of a chicken cast onto the ground. In the West, this same logic works in the Rorschach psychological test: one attends to a chaotic pattern and then a fantasy-image emerges from it. The complete disorder of the pattern confuses and weakens consciousness and allows deep meanings to emerge.

Both the artist and the medium, at certain times, need to reduce the mental level (which can be accessed in a trance) to be able to extract this essential knowledge that then imbues the work with timelessness (like the unconscious itself).

How does it happen? Von Franz says: “Absolute knowledge of the unconscious is like a candle. If we place the electric light of our conscious ego in the center, it is impossible to see the candle or distinguish its light.” The observation of chaotic patterns, then, helps to destabilize the center of consciousness and allows access to underlying knowledge. Primitive societies carry out this operation in different ways in their respective traditions. In China, for example, people read broken turtle shells. In the African Uri tribe, they read a bowl of water and its reflections. In Western psychoanalysis, people in analysis are asked to make (random) abstract drawings/paintings. Normally, the patient begins by drawing a point and from there makes a drawing driven by the unconscious. This pictorial operation is somewhat similar to inducing a partial dream state within the waking state. “It is possible that we are dreaming all the time while we are awake, but due to the brightness of our waking consciousness we are not able to see it,” says Von Franz.

In visual artistic practices (but also in others such as writing or even video recording, which I practice) it makes perfect sense to access these procedures of the apparently irrational to obtain clear images and fundamental truths to transmit or capture in our work. To gaze at the world and at the same time to be able to project it beyond our waking state, or in partial states, is an ineffable driving force of creation and an indisputable mark of great artists. In this way, the image of the golden serpent accompanies us.

Víctor Balcells Matas

In the text of Numbers, the Jewish people, still on their way to the Promised Land, discouraged and fed up with eating only manna, curse Moses and renounce their God. The punishment is swift, coming in the form of “fiery, biting” serpents, replicas of the serpent that Athena had sent to Laocoön and the serpent that had seduced Adam and Eve in Paradise. Moses intercedes, once again, and divine mercy orders him to cast a bronze serpent and hoist it on a pole so that “anyone who was bitten and looks at it will live.” Although the second commandment of the Decalogue prohibits humans from making images, it seems that this passage serves as a justification when searching for convincing evidence in Scripture for “sacred images,” that is, those that refer to Him.

There is a tragic underlying sense of seeing in this passage, which Karma Juliana, by coloring the divine symbol, interprets below.

“Concept art is another artistic medium within visual productions through which a visual product is found for a script, story or idea.

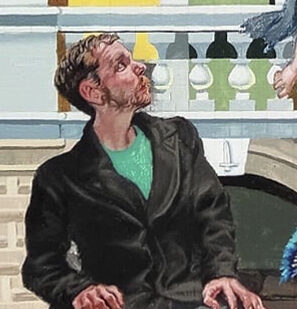

This demo shows a possible adaptation of the biblical episode of The Bronze Serpent within the scope of conceptual art. Where should we look? What do we want and what do we not want to affect us? How many of us are willing to let our spirit grow?

There are many ways to interpret these concepts but in the end the foundation remains the same. In my case, given the interest I have in the world of animation, video games and illustration, I have allowed myself to be carried away by a slightly more naïve vision, influenced by the dream worlds of Studio Ghibli and the simplicity of cartoons.

Faced with an idea and a blank page, a conceptual artist begins to search, soaks up influences and dives into them to try to find the best solution. When working in animation, one has to be aware of details and color contrasts. The more details the more difficult it is to animate by hand, and the less contrast the more difficult it is to interpret what is happening.

The demo consists of an investigation of the serpent itself, treating it as if it were an important object or element within a story for an animated short film. If we were to be technical, the correct name would be prop, which is an object with which the characters can interact and that may or may not have relevance within the story.

Although I have tried to get rid of the religious image a bit, I wanted to preserve the image of the serpent as a link because of its symbolism.

I have always thought of serpents as a kind of guide or “lighthouse,” which is why during the conceptual process I tend to drift towards objects that transmit this idea: a lamp, a candle, or a magical, glowing serpent.

Along with the tests for the serpent prop, there is a keyframe where we can see a fragment of what is happening: In an imaginary world full of ghosts that wander through the countryside, isolated but tied to everything that may happen, there are few who lift their heads and see the light. Something awakens within them.”

Karma Juliana

[Featured Image: Marcel Rubio Juliana. Dibuix anunciador 4]

Marcel Rubio Juliana (Badalona, April 27, 1991). He expresses himself mainly through painting. He is the author of the exhibitions Vastu Purusha (Racoon Projects, 2023), La resurrecció (Fundació Miró, 2022), Hieros Logos (2021) openstudio curated by Margot Cuevas, El retorn a Ripollet (Joan Prats, Art Nou 2020 award), Surfeit ( Arranz-Bravo Foundation, l’Hospitalet del Llobregat, 2018). In the literary field he created with Víctor Balcells Els músculs de Zaratustra (Passatge Studio, 2016), as well as his recent foray into the world of publishing.

Karma Juliana Rubio (Badalona May 22, 1999). Focusing her interest on the world of illustration and animation, in 2019 she began a degree in digital art and 2D/3D animation specializing in concept art and character design. She started working in animation studios helping in both production and pre-production (character design, props, and backgrounds) in Barcelona. She has recently joined the world of video games working on games for Zeptolab Barcelona as a 2D artist.

Víctor Balcells Matas (Barcelona, 1985). He is the author of the novels Discotecas por fuera (Anagrama, 2022) and Hijos Apócrifos (2014), as well as the short story books Yo mataré monstruos por ti (Delirio, 2010) and Aprenderé a rezar para lograrlo (Delirio, 2017). In the field of contemporary art, he is the author of the artist’s book 189 errors (Can Editions, 2017) and was a finalist for the Art Nou award in 2016.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)