Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

We begin this itinerary, in which I intend to study painting not as a fine art but within the universe of the Symbol, as a praxis that leads to knowledge more than as a study of erudition. The topic I deal with is difficult, since painting, like any organism, moves, vibrates, and contracts. Painting, like cephalopods, have many nervous centers that fold in on themselves and escape any definition. An organism, whether in its individual or in its social form, cannot fit into a theory. I will search, instead, for a personal experience in the form of a “journey” that will take us to special places. Although today I will speak, carefully, using theory, throughout the itineraries I will try to speak from practice. The goal of the journey I undertake is to know, and above all, to know ourselves, for as it was said in an old saying, “we do not know anything that is not already in us,” thus alluding to the mnemonic nature of the search.

When speaking of the Symbol, I have nothing new to reveal. These are truths as old as the world, wonderfully described by the Ancients, but in a language that we do not understand and which, in most cases, we find embarrassing and annoying. However, Western thought is getting closer and closer to a conception of the Unity of the world, where the arts and artists, who advance what is to come, grasp by intuition. The spirit of progress still dominates this civilization, although at the moment nothing fills the void between the material form and its source of energy, between the spirit and the corporeal. This void, which is being filled by a culture of distraction, is what the Symbol brings to fulfillment and which I will explain shortly.

A symbol, whatever it may be, is the seal, the visible trace of an invisible reality. It hides as much as it reveals. Its function is to connect, like a bridge, two separate elements that were originally united. These two elements are the two realities in which human beings live, since they understand the profane world in its raw state and the sacred world in its subtlety. The point is that these two worlds coexist but are not united, which produces a rupture and a pendulum movement from one to the other.

What separates these two polarized worlds, an effect of the duality manifested in all that is apparent, is linked by symbolism through vision, which returns it to its unity. In this way, it shares with painting its eminently visual character (paintings enter through the eyes), but unlike painting it is not the result of a convention, despite the fact that its meaning is encrypted in images.

By expressing itself in the world of form, the Symbol has an external (exoteric) part and an internal (esoteric) part. The exoteric part is like the branches, trunk and bark of a tree, and the esoteric part is the sap that runs through the interior of the tree and gives it life. It is important to point out this distinction because most of us stay with the exoteric part without seeing the esoteric part, which is very much hidden. Since the esoteric meaning cannot be transcribed, the exoteric form must guide “the sight” and take it to the source of its origin.

In order to understand a symbol it is necessary to look for the qualities and functions of the thing represented, thereby implying a completely precise accuracy in the figuration. It represents what it is and cannot be anything other than what it is, thus excluding the possibility of any malformation. An example. A number multiplied, that is, repeated, by the number of units that compose it is a number squared. This is ineluctable, it cannot be any other way. It may seem strange to us that it is ineluctable, but it is the esoteric, immutable reality that is being expressed. Another example. The Fish was originally the symbol of Christ, as can still be seen drawn in some places in the catacombs of Saint Callixtus, 3rd century AD, in Rome. Here, the image of the fish replaces the Greek letters of the word, but the secret, “esoteric” meaning was always understood: the coming of Christianity coinciding with the entry of the vernal point, according to the precession of the equinoxes, in the constellation of Pisces.

It is a characteristic of the Symbol to present itself in this ambivalent way.

In the Latin idea of imago we find the same ambivalence, from everything to nothing, from being to non-being. The imago may be nothing more than a false object, a ghost, a fleeting appearance, a simulacrum, but it is also the faithful representation, the portrait, the plausible double offered by the image of the absent object, its dead ancestor, disappeared loved one, a distant instant in time.

Depending on its use, the gaze first passes rapidly over a simulacrum that parades itself before us, a rapid consumption, but then pauses over a form that knows a lot, or everything, of human experience.

Of these two modalities that the gaze offers, it is the second one that is of interest here. The pause in which our gaze rests on beings and things, which discovers what is near in what is far away, the energy of the heart, is what has always frightened tyrants, liars and beasts, which seem to be as numerous today as in the past despite the achievements of our technosphere and the supposed abolition of tyrannies.

The image created by the art of painting, in which each brushstroke is, so to speak, the golden thread that the painter has been able to extract from his or her experience, leads to an evocative magic, in which one of the states of this cruel feeling of emptiness or absence can be compensated. This idea, which could be described as technical positivism, is obviously not new, and was already explained by Seneca in the first century in his Letters to Lucilius, when he wrote: “Portraits of absent friends cause us joy, because they renew our memory and lighten our longing, although with an empty and false consolation.”

This idea can be answered by the Third Song of the Aeneid, in which Aeneas tells Dido how, fleeing from Troy, he landed on the island of Butrotus, where he found his exiled sister-in-law Andromache, widow of Hector. She had built a recreation of Troy on that foreign island, and under the walls of this model, she ordered the construction of a copy of Hector’s tomb. In this imitated landscape of Troy we can recognize a “picture,” an image. It does not trick Andromache enough to cure her of her grief, but it does comforts her. It is no longer an “empty and false” consolation as the arts come to her aid, making her “more relieved.” This is the seed that Baudelaire will make sprout in The Swan (Le Cygne), a mixture of flesh and spirit, doubly converted into art that fills this feeling of emptiness: “Andromache, I think of you!”

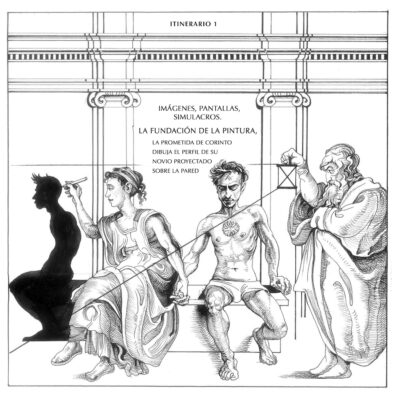

The article ends and I have not talked at all about the fiancée of Corinth, the maiden in love and desperate for the long journey that her fiancée has to undertake. Instead, I prefer that those who are interested should read this legend, told by Pliny the Elder in Latin, to which the first steps of painting are attributed, and let themselves be captivated by its story, so simple and so beautiful.

[Featured Image: Marcel Rubio Juliana, Dibuix anunciador 1]

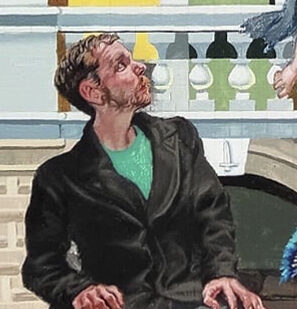

Marcel Rubio Juliana (Badalona, April 27, 1991). He expresses himself mainly through painting. He is the author of the exhibitions Vastu Purusha (Racoon Projects, 2023), La resurrecció (Fundació Miró, 2022), Hieros Logos (2021) openstudio curated by Margot Cuevas, El retorn a Ripollet (Joan Prats, Art Nou 2020 award), Surfeit ( Arranz-Bravo Foundation, l’Hospitalet del Llobregat, 2018). In the literary field he created with Víctor Balcells Els músculs de Zaratustra (Passatge Studio, 2016), as well as his recent foray into the world of publishing.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)