Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Talent knows no age. Its essence has nothing to do with the wild bird of youth, nor does it come in autumn colors. It is true that in the history of culture one can highlight exceptionally prodigious, precocious creators with an early-morning drive: Mary Shelley, Rimbaud, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Mozart, and Artemisia Gentileschi. The sun had not yet risen when their sensitivity, their instinct, their audacious creativity were already taking flight. In reality, however, talent lacks a precise date for blossoming and is, rather, a heartbeat that slowly and steadily unfolds its rhythm, sometimes in the spirit of an unexpected volcano erupting. This has happened with many other artists, such as Gauguin, Defoe, Lucy Schwob, Camille Claude, Vivian Maier, and José Saramago, framed by sudden and deserved attention on the maturity of an unknown body of work, rooted in the passage from the past to the present.

One never knows from which train success will descend or to which station it will arrive. In that journey, however, women tend to be overlooked by the light of triumph, even though their work merits it. Sometimes, less frequently, this is due to their own choice to live in the shadows as a refuge as a rebellion against the marketplace, or because of an avant-garde vocation beyond their own time. The Swedish painter Hilma af Klint is a symbolic example. A pioneer of abstract art before the movement even existed, at least a hundred works attest to her artistic discourse five years before the publication of Kandinsky’s Concerning the Spiritual in Art and before Malevich added his equally brilliant mark to the scene.

Hilma af Klint, La Paloma series, Nr. 8, 1915

Hilma af Klint’s reasons for this absence are unknown. There is no record that sheds any light on the matter, just an intuition that her decision comes her desire to avoid being subjected to scrutiny or fame and for her voluntary hibernation from the public’s eye while she secretly maintained a prolific output. Few artists controlled the reins of their destiny like she did, subjecting their creativity to the idea that the world was not ready to understand the avant-garde nature of their art. Before her death, she left written instructions that her enigmatic paintings, with their powerful, constructive chromatism and esoteric spirit, should not be exhibited until twenty years after her passing, a further period of time for her talent to mature. Her sublime, mature work would go on lead to an artistic explosion in the mid-60s. I didn’t discover her in her entirety, beyond a few references, until 2013, at her splendid Málaga Picasso Museum exhibition, where I was struck by the modern balance of her geometric compositions and the monumental scale of some of her paintings. Her innovative language shone, garnering widespread acclaim beyond the specialized art world.

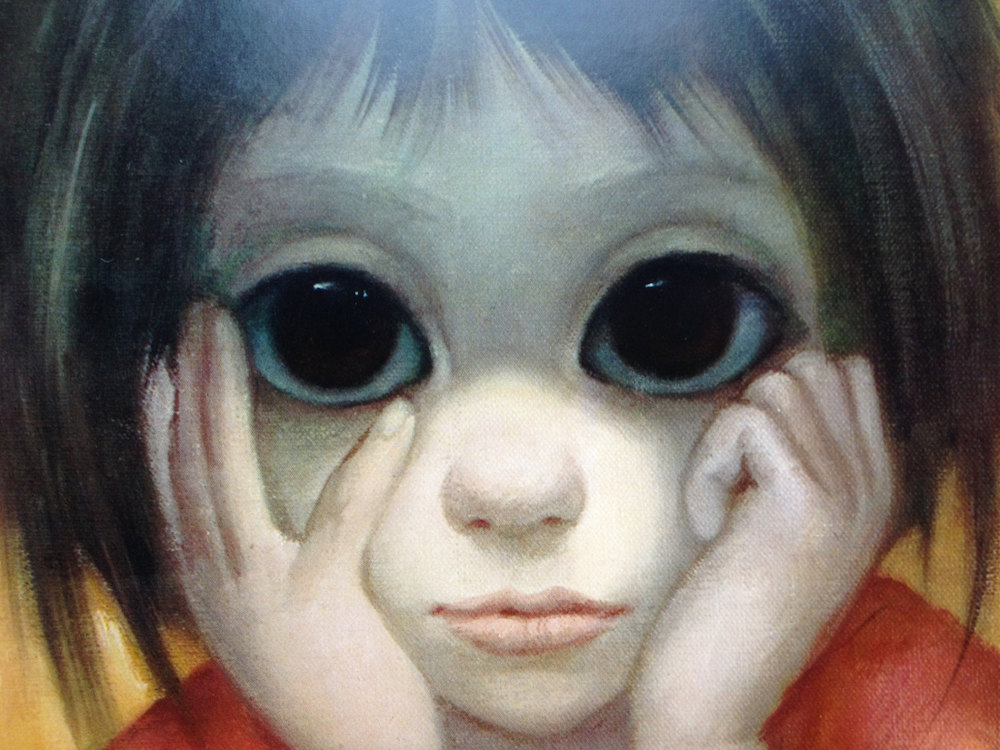

At other times, praise for an artist’s work is delayed because, despite talent, social circumstances and emotional alliances facilitate a kind of identity theft, a confinement disguised as paternalism in the face of others’ insecurity, and, of course, manipulation. The periods of forced obscurity of Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette are well known. Her series Claudine at School, Claudine in Paris, and Claudine Goes to the City were signed by her first husband, Willy (Henry Gauthier-Villars). In the 1960s, the American artist Margaret Keane painted portraits of children, women, and animals with enormous, introspective eyes, imbued with dark melancholy and in a kitsch style. These portraits were signed by her husband, Walter Keane, celebrated for his talent and who enjoyed great success among Hollywood art collectors such as Natalie Wood, Joan Crawford, and Kim Novak. Only after their divorce did Margaret Keane reveal her authorship. In 1986, she won a lawsuit in which the court ordered them both to paint on the spot, before the eyes of the law, delivering poetic justice and the verification by the public and art experts of the vulnerable gaze of her subjects with sad eyes. Her story of being rendered invisible was captured by Tim Burton in the film Big Eyes.

Margaret Kane, Little Thinker (detail), 1963

This vampirism did not take hold of the French artist Berthe Morisot, wife of Eugène Manet, an artist who did not achieve the success of her brother Édouard Manet. Due to jealousy Berthe was subjugated by her secondary, painterly husband. Her skill in capturing light, color, and the intimacy of everyday life got her invited to the Salon de Paris where, at the age of 24, she participated in the first Impressionist exhibition alongside Monet, Cézanne, Renoir, and Degas. Despite her mastery and critical acclaim, her peers and the critics’ inner circle, including her husband, relegated her to the boudoir of her studio, labeling her a “female artist” as a way to hinder her career. Nevertheless, ten years later, in 1874, Berthe Morisot became a key figure in the Impressionist movement, and is now a talent safely housed in the Marmottan Monet Museum in Paris where she reigns as one of the great ladies of painting.

Berthe Morisot, Reading, 1873 (Wikimedia commons)

When is the best time to receive recognition for one’s work? Is it preferable when the worm of a creative gift transforms into a hypnotic butterfly that surprises people with its wings? As an outstanding evaluation of a meritorious and established career? Can the flames of premature recognition destroy an artist’s inspiration? What good is it if it is achieved when the artist is no longer living and cannot enjoy it? We can answer these last questions with the aborted flight of the immeasurable Rimbaud, enfant terrible of poetry, and with the self-destructive passions of Modigliani and Van Gogh, victims of economic hardship and artistic incomprehension, before the noise and colors of their anguish and temperament were silenced. We can create diverse debates and conclude that what is important is that this recognition occurs, and that it serves as an impetus to progress, to creativity, to dissatisfaction, to search and the discovery.

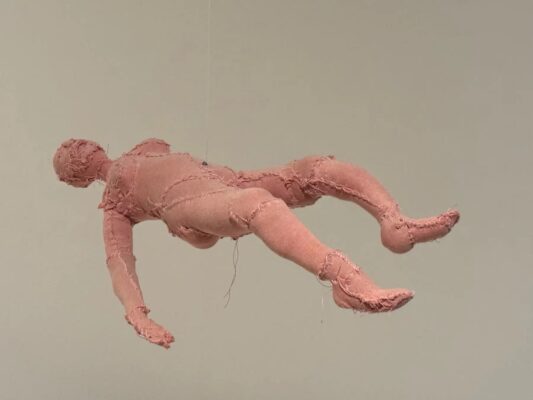

Sometimes this communion happens in the final stretch of life and artistic career. Buttons of iron, fabrics, and wood makes up the talented work of Louise Bourgeois, tireless since her youth. Her first sculpture exhibitions were held in 1945 and her first solo show, Seventeen Standing Figures in Wood, in 1949. Success gradually paved the way for her with a fragile hand, wrapped in the uncomfortable glove of the underground, providing her with steps to ascended with firm footing. This includes her 1978 exhibition Confrontation at the Hamilton Gallery of Contemporary Art in New York, and her performance A Banquet: A Fashion Show of Body, presented within the installation, where models paraded around in latex outfits. This was the moment when the spotlight found her. Bourgeois was 67 years old and had to wait four more years for the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York to dedicate its first retrospective to her, in 1982, the first the museum had ever given to a woman. A consecration. The rise to the top at 71 fueled her autobiographical catharsis, resolved through visual language and exploratory works of the human figure and its fragments, addressing themes such as betrayal, anxiety, and loneliness.

In 2011, a year after her death at 99, one of her works, the celebrated Spider, sold at Christie’s for $10.7 million, a record at the time for a work at auction and the highest price ever paid for a work by a woman. It is not known whether, upon the sale of her work, a blue butterfly hovered over the famous sculpture, scattering the golden dust that confers immortality upon art.

(Featured Image: Louise Bourgeois, Arch of Hysteria, 2000, under (cc) instagram by Galerie Karsten Greve)

Guillermo Busutil is a writer, journalist, and cultural manager, winner of the 2021 National Prize for Cultural Journalism. He is a member of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of Barcelona. He is responsible for La Ventana del Nautilus on RNE’s El Ojo Crítico Fin de Semana, and is an art critic for the culture supplement of La Vanguardia; literary critic for Zenda and Litoral, and participates in the political discussion program Hoy por Hoy on SER Málaga. He has curated photography and painting exhibitions such as Petricor; El perfume de la lluvia, El artista en su laboratorio, and Maximov, among others. He is also the author of exhibition catalogs for Manuel Rivera, Juan Béjar, Diego Santos, Rafael Alvarado, and José Seguiri.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)