Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Yuderkys Espinosa, one of the prominent academic and activist voices of decolonial thought, especially decolonial feminisms, spoke to us about the issue of “reparation and restitution” from her perspective.

Yuderkys Espinosa Miñoso: I recently returned from the Afrodescendant Summit in Puerto Rico, which has been ongoing for three years now, coordinated by the great poet and writer Mayra Santos Febres. This 2024 summit was dedicated to the issue of Haiti, and there was much discussion about the topic of “reparation.”

Regarding the agenda of reparation, from what I’ve been able to trace without being directly involved, I can identify at least two positions. To illustrate this, I recall the slogan of the Ayllu[1]A collective of anticolonial actions and sexual and gender dissidence. We carry out artistic research. Madrid/Barcelona. group “Return the Gold,”[2]Relational Ontology arises in the so-called ontological turn of the social sciences with thinkers such as the Colombian Arturo Escobar, who states: “…they are those in which the biophysical, … Continue reading which can be interpreted in two ways. The first pertains to gold as its monetary value within the context of capital. Thus, reparation would be monetary, which some decolonial intellectuals and comrades, like Agustin Laó Montes and Ochy Curiel, refer to as the Liberal agenda of reparations. This position, I understand, is leading the discussion at the United Nations level under the influence of the U.S., Canada, and European countries, but it seems to be endorsed by figures such as Epsy Campbell, former First Vice President of the Republic of Costa Rica and former Chair of the United Nations Permanent Forum on People of African Descent. The proposal is to create a monetary fund dedicated to people and communities of African descent. I’m speaking from the Afrodescendant agenda, and I’m not sure what the debates and positions within the movement are on this point.

On the other hand, there are more radical positions, often from those identified with decolonial struggles, if one could call them that. From this perspective, when we talk about “Return the Gold,” we are appealing to a metaphor where gold does not relate to money and monetary value. What was taken, what has been exploited, what was stolen from our territories is much broader and deeper. Not everything taken was gold. What was taken were ways of life, of doing; our freedom was taken, our territories were seized, and models of life that existed there were either stolen or destroyed. Thus, reparation would include considering culture, epistemologies, lives turned into commodities from populations taken from Africa through the slave trade. In slavery, there is no surplus value as such, the enslaved person is not recognized as human, thus there is no pay as such, merely the provision of conditions to barely keep you alive to continue working and/or to keep producing new slaves. Thus, the historical debt is not payable through monetary sums. How can a price be put on destroyed worlds, on human and non-human populations exploited, destroyed, disappeared?

Reparation here becomes something else, not the easiest solution in terms of money. Money that is already bloodstained, right? Because that money is the consequence of systematic exploitation, not only of human beings but also of non-human beings. The issue of reparation would have to do with how to stop the advance of an extractivist model, the model of death as many territorial movements in Abya Yala call it. Stopping this modern world system that does not stop in its expansion and is leading us to the destruction of everything existing. It is leading us to the possibility of the planet’s disappearance. This idea of reparation resonates with certain efforts that have emerged in Europe in recent years against climate change, ecological movements caring for the planet. Because much of what was destroyed and needs to be repaired are models of life, of existence based on principles of complementarity and mutual care. Ultimately, it would be about seeing the reparations agenda as an opportunity to halt the potential disappearance of the planet.

Similarly, one of the issues discussed at the Afro 2024 Summit was that we cannot think about and debate reparation without putting Haiti at the center. Because we talk a lot about Palestine but little about Haiti, and this is at least suspicious. No one talks about the genocide in Congo, in Sudan, and other peoples devastated by the advance of coloniality. This is urgent. Haiti in particular is painful for its feat of being the first people to rise against slavery and the colonial enterprise. Precisely for this struggle, Haiti was historically condemned to a dead end. Today, it is one of the most impoverished countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. The poverty and socio-political crisis that Haiti has been experiencing for decades is related to being forced to pay a massive debt to France as compensation for the income it lost by abolishing slavery. Paradoxically, Haiti was subjected to the first reparation, and it was reparation for the colony.

Press conference for the exhibition “Anti-Futurismo Cimarrón”, held at Arts Santa Mònica and Centre de Image La Virreina (Barcelona, 2023). Courtesy Yuderkis Espinosa Miñoso and Katia Sepulveda

Nancy Garín: And in terms of what we might call culture and the art field?

Y.E.M.: If we talk in cultural terms, about creative productions and art, there is also a historical debt with our peoples as Europe appropriated and stole many artifacts and artistic pieces produced by our societies. This is an issue inscribed in the critical agenda of the art field and decoloniality. In a text I wrote recently, I question whether the reparation agenda is about entering the Museum or blowing it up.

Because part of the movement of artists from the global south has advocated for reparation in terms of inclusion, that is, demanding space within the museum for Indigenous and Afrodescendant artists, and claiming the value of their works in the art market. It can be stated without fear of being wrong that the decolonial critique of the art field has resulted in the opening and production of small niches and spaces of inclusion and appreciation of works by artists from worlds discarded by modernity and seen as incapable of creating beauty. That is important, of course, and for our artists, it offers hope to improve their lives in such harsh conditions.

However, we know that this is barely a superficial wound to the system. The harsh conditions continue as often entering the museum means entering with a low budget, as if they were doing a favor by letting them in. In concrete terms, there is no change in the valuation standards of the works, neither monetarily nor in terms of art criticism, which remains regulated by standards produced by the West, where collective productions and those from non-European peoples are still seen as crafts or lesser art.

In recent years, initiatives like the Museo Reina Sofía have acquired pieces for their permanent collection from racialized artists or those from the global south, but in most cases, these are donations. Thus, many of these reparation initiatives remain limited to allowing entry into their spaces but under unequal conditions. The museum as a colonial institution allows some to enter, assuming that merely allowing entry is already sufficient.

We remain trapped in a kind of liberal solution to the issue of reparation. Because getting to the heart of the matter would imply revisiting the foundations of the art field. What is considered beautiful, what ontologically has the quality and power to be considered art in Europe, what counts in art history. The criteria for determining what is beautiful, what is art, this is a topic that should be part of the reparation debate.

On the other hand, we should also consider that many of the great artistic movements that have occurred in Europe and have value in art history often began with theft, an extractivism of cultural productions from the peoples of Africa, Latin America, and other regions.

N.G.: Regarding this issue of returning objects extracted during colonization and held in Western museums as a gesture of “decolonization” or reparation, now being posed by European institutions, under their rules, of course. Do you think it can be a gesture of “reparation and restitution”?

Y.E.M.: I recall a reflection by Gloria Anzaldúa, where she says that the difference between modern art and artistic works in ancestral worlds is that for us, what they call artistic objects are actually part of the continuum of community life. It’s about seeing these productions as part of the reproduction of collective, everyday, or transcendental life. For Anzaldúa, as for Maya art, art or creative production has a community, spiritual, and world-producing function. Quite the opposite of what the art field does within European modernity, which separates the product from life and turns it into an object for contemplation. Thus, the product becomes an item with exchange value, exhibited in spaces outside of everyday life; it is hung on a wall.

The problem formulated from the metropolises by curators and museum administrators about how to care for “objects” returned in a way that guarantees their preservation, presented as an obstacle to the effective return of the “stolen pieces,” is a problem clearly formulated from a Western treatment. In our traditions, this would not be the substantive question. Object preservation is a Western concern, but we know there are other ways of constructing memory that are integrated into doing and living. Furthermore, our peoples have had ancient technologies for preserving what is necessary. We are talking about two very different languages. Each people will have their way of how to safeguard and protect the memory and materiality of those memories. It probably won’t be the way the West considers it should be done, and it will be the way our peoples decide.

On the other hand, you can be sure that in this race, the West will end up defining and imposing the conditions of preservation. Because the museum, curators, galleries, etc., continue to impose their preservation model. Communities will have to fight to maintain their autonomy over how to safeguard what is returned, if it is indeed returned, so that it becomes part of their memory. But this definitely cannot end there. If the agenda of returns and reparations within art remains limited to returns, it is a small part of what needs to be done.

A reparation agenda should aim, first and foremost, for art institutions defined by Europe and the U.S. to admit that they do not have, as they have claimed, the authority to define what has value and beauty in the world and what is or is not art. And this is a discussion we see little of. A group of intellectuals discussing art and decoloniality did so in the first decade of this century. Walter Mignolo, Adolfo Alban Achinte, Alanna Lockward, among others, began a movement reflecting on these issues. Although the movement has somewhat impacted the art field, in terms of questioning the foundations of what defines what is or is not art, it was reduced to a small group of intellectuals and artists from the “third world.”

With Katia Sepúlveda, we have been working for a few years on a research and exhibition project we call “Anti-futurism Cimarrón,” and we found in Arts Santa Mònica and La Virreina[3]Various authors. Colectivo Ayllu compilation. “Devuélvannos el oro. Cosmovisiones perversas y acciones anticoloniales” (Give us Back the Gold. Perverse Worldviews and Anticolonial Actions). … Continue reading a space to bring other conceptions and work differently, starting with the question of what the world would be like if Europe never existed and applying it to the art field to challenge the foundations that sustain modern art. The proposal envisions curation and the work of racialized artists as a means of healing the colonial wound, reclaiming the idea of the artist as a bridge between materiality and the spiritual-community. We’ll have to see what impact this has on these European institutions we work with. I’m skeptical, but I hope to have left a mark there.

The goal remains to see how we can insert ourselves into the heart of this so-called art system, which is part of the modern world system and coloniality. The problem is not only external but internal as well. What we have seen is that the obstacle does not only come from outside; the danger is when an entire cohort of cultural and art workers, even those claiming to be committed to decolonization, accept the European modes of production and evaluation of art, risking ventures that dare to experiment and transgress Eurocentric rationality and imposed norms, disqualifying them. We must also beware of these people as they operate in service of the status quo and the perpetuation of the coloniality of art.

Part of the exhibition “Anti-Futurismo Cimarrón” at Arts Santa Mònica (Barcelona, 2023). Courtesy Yuderkis Espinosa Miñoso and Katia Sepulveda

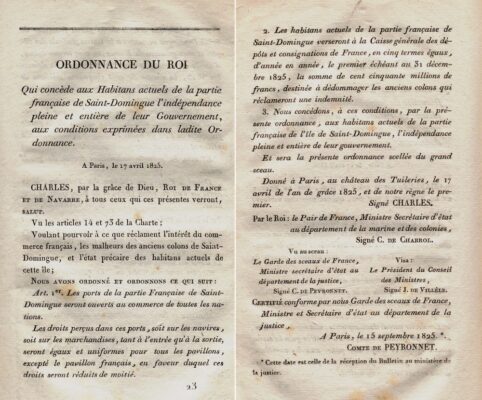

(Front image: Ordinance of 17 April 1825 granting Independence to Haiti under economic reparation to the French colonists who left the territory. Image copyright CC. Archive: Ordonnance du 17 avril 1825 qui concède l’indépendance aux Habitans actuels de la partie française de Saint-Domingue.png – Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre)

| ↑1 | A collective of anticolonial actions and sexual and gender dissidence. We carry out artistic research. Madrid/Barcelona. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Relational Ontology arises in the so-called ontological turn of the social sciences with thinkers such as the Colombian Arturo Escobar, who states: “…they are those in which the biophysical, human and supernatural worlds are not considered as separate entities, but instead establish links of continuity between them. That is, in many non-Western and non-modern societies, there is no division between nature and culture. Development (once again) is questioned: within certain ideas and, much less so between individual and community, there is no “individual” but just people in a continuous relationship with the entire human and non-human world, throughout the ages.” Escobar, A. (2014). Sentipensar con la tierra: nuevas lecturas sobre desarrollo, territorio y diferencia (Feelingthinking with the Land: New Ideas about Development, Territory and Difference), Medellín, UNAULA Editions. |

| ↑3 | Various authors. Colectivo Ayllu compilation. “Devuélvannos el oro. Cosmovisiones perversas y acciones anticoloniales” (Give us Back the Gold. Perverse Worldviews and Anticolonial Actions). Colectivo Ayllu, Matadero Art Residence Center, Madrid, 2018 |

Yuderkys Espinosa Miñoso is an Afro-Caribbean writer, researcher and teacher, a precursor of decolonial feminism and a critic of the “coloniality of feminist reason”. She is the director of the Caribbean Institute for Decolonial Thought and Research and a founding member of the Latin American Group for Feminist Studies, Training and Action (GLEFAS). She has received several awards, including CLACSO’s Berta Cáceres Research Award and the Käte Hamburger scholarship at the University of Heidelberg. Curator of the project “Antifuturismo cimarrón” with 16 racialised artists from Abya Yala. Author of essays and academic texts, and editor of key compilations of decolonial feminism such as “Tejiendo de Otro modo:Feminismo, epistemología y apuestas descoloniales”.

She has published numerous essays and books and has been translated into English, French, Italian, German and Portuguese. Her recent publications include “Decolonial Feminism in Latin America: An Essential Anthology,” “Decolonial Feminism in Abya Yala: Caribbean, Meso, and South American Contributions and Challenges,” or “De porqué es necesario un feminismo descolonial” and her collection of poems “Laquevuelve”.

NANCY GARÍN GUZMÁN (Valparaíso, 1972) is a journalist and art historian, works on projects related to critical thinking, new pedagogies, archives, memory and decolonialism. She studied the Independent Studies Program at MACBA (PEI). As a member of the Etcétera collective and the Errorist International. She has been part of research groups such as Peninsula: Colonial processes and artistic and curatorial practices (2012 -2018) and Contraimaginarios (Postpandémicos) (2022-2023). She is part of the research and production platforms Equipo re (2010 to present) with whom she has been developing the project Anarchivo sida and the group Espectros de lo Urbano (2017 to present) research around the urban as part of the colonial, capitalist and patriarchal machinery. During 2022-2023 she has been resident at ADKDW Cologne and is part of the research group Contraimaginarios at Arts Santa Monica/Barcelona . She has worked as a teacher and mentor/tutor in different spaces of critical and experimental pedagogies. She is currently teaching at PEI/MACBA (2023-2024).

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)