Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

The scenes of buffalo hunting in the caves of Lascaux and Altamira are not only considered the earliest artistic expressions of mankind; each scene could also be regarded, from the conception of ‘sympathetic’ magic by Sir James Frazer, as a sort of animistic portal that invoked, in a sort of prediction, the materialisation of a future action — the hunt. Governed by the principle that like produces like, exemplified by the Dayak witchdoctor simulating labour contractions in a room close to a woman giving birth, in Frazer’s classical study of compared anthropology entitled The Golden Bough the scenes of buffalo hunting nurture a fundamental relationship between man and the world that is not only one of survival, a link that artistic practice has channelled in different ways in different civilisations. Even in the periods in which man was once again the centre of the cosmos in the face of the divine, the mysterious access to the pineal gland, the famous Eye of God encrypted in the scene of the creation of man painted by Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel, and the portraits of conspirers depicted by Boticcelli in the Piazza della Signoria as a form of visual curse indicate that the Renaissance didn’t only imply the rebirth of classical art and thought but also that of the symbols in hermetic tradition, magic and esotericism. Overshadowed during the Enlightenment and Modernism, occultist traditions were revived by Romanticism and the following century by the creationist Adamic impulse of the avant-garde movements. They flourished again in the fifties, according to the thesis proposed by Black Light. Secret Traditions in Art since the 1950s, the present exhibition at the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona (CCCB).

An inspiration for Sufism, the esoteric current within the Shiite branch of Islam, black light represents the last stage of mystical ecstasy. The itinerary suggested by curator Enrique Juncosa isn’t limited to the esoteric traditions of official religions but covers the wide spectrum of mysticism, esotericism, hermetism and occultism, embracing also Zen Buddhism and Taoism. Black light is a sufficiently ambiguous and comprehensive metaphor to favour a Baroque lighting – like a black sun – the result of tensions and contradictions, over the influence of these eclectic traditions on artistic and countercultural practice since the fifties.

Through three hundred and fifty works by forty-eight artists, this exhibition proposes a chronological survey of techniques and formats as different as painting, drawing, sculpture, film, music, photography and installation art. Along with woks by renowned artists like Joseph Beuys, Antoni Tàpies, Barnett Newman or Agnes Martin we come across others by exceptional figures such as the painter Forrest Bess and his modest small-format landscapes inspired by Jung, or contemporary artist Suzanne Treister, who combines new technologies with the tarot and alternative systems of beliefs. The show also includes a series of artefacts, books, comics and documents by counterculture gurus and occultist symbols encoded in pop, rock (The Beatles, David Bowie, The Rolling Stones, Pink Floyd) and jazz (Sun Ra) records of the sixties and seventies, or the short films by cult directors Kenneth Anger and Derek Jarman. In addition, parallel activities like Radio Éter, a radial podcast that invokes the magical abilities of the radio in its early days; the Beyond Reason lecture series that will transcend the limits of the mind, the Xcèntric Archive and the Gandules film season complement the exhibition.

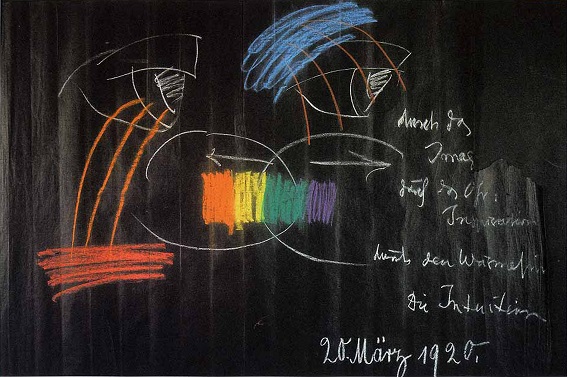

Rudolf Steiner: Without Title (20. 03. 1920). Rudolf Steiner Archiv, Dornach

Loyal to the bond between master and disciple that shapes the internal hierarchy of secret doctrines, the show examines the influence of five gurus worshipped by most of the artists on display and signalled as a source of inspiration. Armenian mystic George Gurdjieff, creator of theosophy, whose followers included Madame Blavatsky, the mother of spiritualism (depicted in the suggestive hyper-realist sculpture by Polish artist Goshka Macuga) and Rudolph Steiner, who combined science and religion with anthroposophy as a total life experience; his are the mental schemes drawn on a blackboard with coloured chalks on display at the CCCB. Furthermore, there are continuous references to archetypes and the collective unconscious made by Carl Gustav Jung, the psychoanalyst who brought psychoanalysis into contact with esotericism and Eastern philosophical traditions, besides first editions, drawings and paraphernalia created by Aleister Crowley, who is perhaps the most influential Satanist in pop culture. These five gurus are joined by prolific author Alejandro Jodorowsky, who used psychomagic to revive the transformative power of certain esoteric practices in our prosaic everyday lives.

The exhibition also expresses the revisionist relevance of so-called primitive cultures and the recognition of art as practical magic and of the artist as a wizard, magician or shaman. This transmission of art as a path to discovering hidden truths, as a channel for inner experience is found in the only interactive work in the exhibition, Dream Machine (1962) by American film maker Brion Gysin, an artefact which, through a light projected on a revolving screen, generates a stroboscopic effect that animates a transcendental experience, a mystical communion or a higher vision in the spectator. Although this experience is internalised by the widespread increase of stroboscopic lights in discos, the search for the interactive artefact is a vestige of the psychedelic desire to peep into the abyss of the irrational, to suspend judgements based on formalism and materialism and experience, against our will, the strength of the self that multifaceted artist and writer Henri Michaux disowns in a text that is a statement of the exhibition. To paraphrase Michaux, it would be wrong to believe that, conscious of the paths, we can find them again because having known worlds of ecstasy, we will be able to enter them once more at will. No way. Will has nothing to do with it, nor do conscious desires.

With its intimist lighting and silent atmosphere, the journey suggested invites viewers to contemplate and reflect on the processes in which the artist became a medium and art an invocation. However, if we look closely at the works on display from the eighties onwards, such as those by Terry Winters, Philip Taate, Fred Tomaselli and Wolfgang Laib, it is obvious that recent decades aren’t characterised by the intense spiritual investigation of earlier periods. More than become a subject of these theophanies, spectators contemplate and reflect on these dark forces that converge in the artistic discourse of the past that, like the present paradigm of theoretical physics, make uncertainty the rule and encourages them to wonder what room is left for the irrational and for the occult in the materialism of today.

Wolfgang Laib: Passageway, 2013. © Wolfgang Laib

Ana is fascinated to dive into books and movies, to approach with caution those tentacles that lie in the depths and to return to count what she has seen. She has published “Este es el momento exacto en que el tiempo empieza a correr” (Premio Antonio Colinas de Poesía Joven), the novels “La puerta del cielo” and “Hemoderivadas”, “Constelaciones familiares” (short stories, Premio Celsius Semana Negra de Gijón) and “Érase otra vez. Contemporary fairy tales” (essays). She currently lives and works between Berlin and El Paso, Texas, where she is a Bilingual MFA Fellow in Creative Writing at UTEP. Some of her texts have been translated into Portuguese, Italian, Polish, Lithuanian, German and English.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)