Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Textiles are made by knotting, weaving, crocheting or bonding individual strands of fibre together to create an interwoven, interconnected, networked whole. If a textile has ruptured, one can mend it using darning – a mending technique where one vertically and horizontally interweaves threads across the fabric’s hole. To help me think through interconnection as a practice of mending within the academy, I would like to refer to Donna Haraway’s notion of the situated knowledge, bell hooks’ engaged pedagogy and the thematic focus on Embodied Knowledge(s) within the minor studies course Cultural Diversity.

In critiquing the gaze of scientific objectivity, Haraway introduces situatedness to propose that knowledge is always born of a context, situated in time and space, and inconceivable without a multitude of relations, which is say that knowledge is entangled and interwoven and not abstracted and separate. The objective gaze, she argues, comes from the position of the white men who “claim the power to see and not be seen, to represent while escaping representation.” [1] Donna Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial,” Feminist Studies, Vol. 14, No. 3 (Autumn, 1988) p. 575-599 It is this position that we supposedly call “neutral”. She continues:

All Western cultural narratives about objectivity are allegories of the ideologies governing the relations of what we call mind and body, distance and responsibility. Feminist objectivity is about limited location and situated knowledge, not about transcendence and splitting of subject and object. It allows us to become answerable for what we learn how to see. [2] Ibid.

Situated knowledge is for Haraway a feminist objectivity, one that understands that intellectual, emotional, sensorial, and physical knowledges are enmeshed, and human and non-human life are interwoven and in relation to one another. To me, embodiment is to be situated, describing the fundamental condition of being a part of the fabric of life.

The thematic focus of the Cultural Diversity minor where I’ve taught for several years is the notion of Embodied Knowledge(s). Echoing Haraway, we take the position “that without the bodily, we would not be able to organize ourselves in our environment: we would not know where/what we are, what/how we are learning or how we can communicate about our feelings, experiences and modes of being.” [3] Teana Mammah-Boston, Cultural Diversity Minor Course Outline. Themes and Goals. Last accessed Nov 2019. https://1920.mywdka.nl/WDKCDVPRAM/minor/theme-and-goals/ The biggest difference teaching in this course compared to the various other courses I’ve taught previously within Willem de Kooning Academy is that we challenge the Enlightenment idea that the production and formulation of knowledge can only be a rational, abstracted and external affair. Many courses have an approach that tries to tackle large, complex problems – for example global politics or climate crisis and sustainability – but overlook the daily implications of how these crises influence us locally and on a bodily level. Generally, there are expectations to produce work that addresses these large complex subjects, however students often feel removed from them because connections between societal, community and personal links have not been made palpable. As a result, students feel pressure to make grand concepts external to themselves, rather than listening to their experiences or working within local contexts.

This disconnection mirrors my own formal education in Rotterdam, where the default teaching position was the divorce of the mind and body, emotional and political. In the design educational context where abstractions were valued, I felt that embodied knowledges had no place in my work. That is why I feel a personal obligation as a practice teacher working in Cultural Diversity Minor to begin where the senses begin – that is, in our bodies – by interrogating how the body organises our knowing, feeling and being, and by extension how that shapes our understanding of the way we gaze on our own bodies and those of others. [4] Ibid. We should work harder to legitimise the idea that it’s perfectly valid for students to derive concepts and ideas from their experience of the world while the body is fully engaged in all of its senses – embodied, critical and responsible.

Another way of looking at embodiment is through bell hooks’ engaged pedagogy – an understanding of wholeness that places importance on the relationship between the teacher and students as well as on the interconnection between mind, body and spirit. This kind of pedagogy approaches the student as a “whole” human being striving for intellectual and creative nourishment as well as knowledge on how to live in the world. It emphasises wellbeing; students and teachers alike wish to heal and grow, and they are empowered by the process. [5] bell hooks, Teaching to Transgress (Great Britain: Routledge, 1994) p. 15

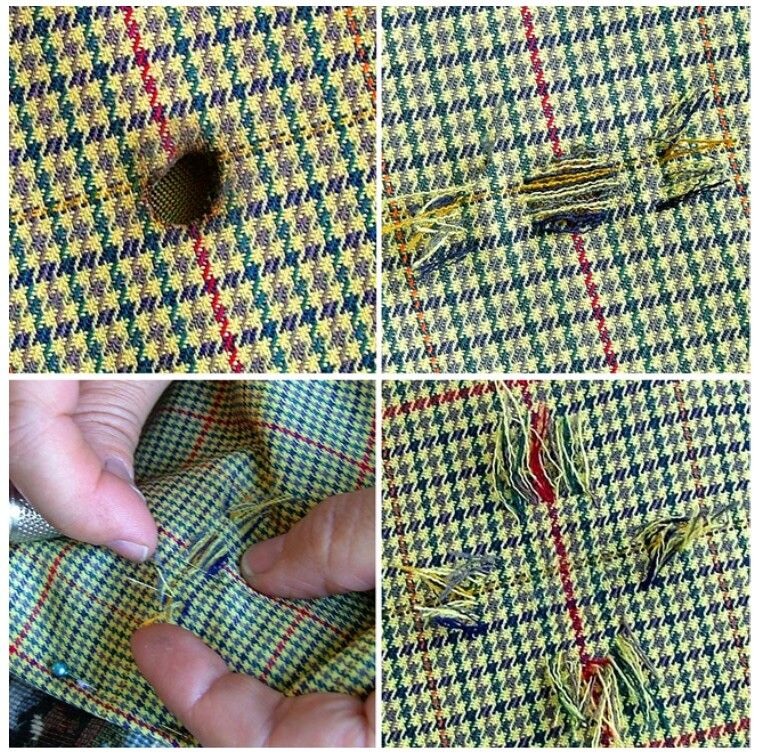

Invisible mend by Isabelle Godfroy. Source: http://www.stoppage-art.com/metier.html

A few years ago, I had a breakdown. It is hard to describe what really happened, but it was as though dissenting ghosts of my past halted my body and forced me to confront that which needed to be confronted. It forced me to bring to the surface what I had repressed for so long. Sometimes I’ll refer to this moment as the shedding of an armour, one that had been slowly calcifying since early childhood to shield me from the long-term exposure to painful experiences.

In the months after my armour was taken off, what I found underneath were untreated wounds that had been accumulating and festering for thirty years or so. During this time I was still teaching but not making work in the same way as I did previously. One of the few things I could do was mend damaged clothes: a hat with a thousand holes, a forgotten sweater, overalls that I’d worn for over a decade. I returned to my first love – textile – something I had never previously allowed into my “serious” art and design practice.

In my state of fragility, mending and journaling were all I could muster the energy for. I retreated to textile and text. Here I mean retreat in both senses of the word: a withdrawal from moving forwards and a safe haven to rest and recharge. Later on, I learned that the root of the English words “text” and “textile” comes from the Latin word texere, meaning to weave. Many expressions about writing come from the rich world of cloth-making. According to an ancient metaphor, “a thought is a thread, and the raconteur is a spinner of yarns – but the true storyteller, the poet, is a weaver. […] After long practice, their work took on such an even, flexible texture that they called the written page a textus, which means cloth.” [6] Robert Bringhurst, The Elements of Typographic Style (Hartley & Marks, Publishers, 1996) p. 25 It was such a pleasant surprise to learn that cloth-making predates text-making. I had assumed cloth-making succeeded text-making and not the other way around, which goes to show my internalised bias towards intellect over craft. Journaling allowed me to weave disjointed thoughts together in an attempt to find imaginative ways to dress psychic wounds, and one such way was that of mending textile.

Textile has been my elementary mode of expression for as long as I can remember, despite being ashamed to be public about it. Although I have done some textile work in the past, I hid textiles in my closet – working with the medium of textile was something I wanted to seriously explore but was too afraid to be judged. Steeped in the belief that clothing and textile were unimportant, feminine, superficial, too ordinary, without “real” agency and – god forbid – politically ineffective, I was the most judgmental figure towards myself.

Why is it that textile and fashion are often looked down as a lesser form of making in art and design education? Is it because textile arts have long been feminised and restricted to the domestic sphere? (Yes, obviously.) Have crafts been seen as lesser forms of knowledge because they pertain to tacit knowledge? (Yes, also.) This hierarchy of knowledge is reflected within different education contexts I’ve been. In Sydney were I first studied, fashion was only available as a vocational study, whereas design and art were available at university level. Throughout my Dutch education, where all creative studies are within the vocational education system, fashion studies at the WdKA caters to the commercial industry, with little critical discourse.

Perhaps another reason why we relate to clothing in this superficial way is because it is linked to the relationship between the surface and personhood, as suggested by fashion scholar Sophie Woodward. Western thought separates the inner intangible self, she claims, which is located deep beneath from the “frivolity” of the surface. [7] Susanne Kuchler and Daniel Miller, ed., Clothing as Material Culture (New York: Berg, 2005) p. 21 According to this Western philosophy of being, clothes simply hang on the periphery of one’s body and are of no real importance compared to the body’s inner sanctum where one’s “true self” resides. This perspective, however, doesn’t account for alternative and non-Western understandings that the self is simultaneously located and also constructed – that is to say that the self “lives” within us but also “lives” on the surface as appearance, which is constantly shaped by external relationships. One is not more important than the other.

From a psychological perspective, in Trauma and Recovery Judith Herman talks about recovery as reconnecting or creating new connections to pieces that have been torn apart through trauma. To understand this psychologist’s view in relation to pedagogy, perhaps the rupturing that occurs within an institutional setting in the West is precisely the “imperialist, white supremacist, capitalist, patriarchal” authoritative legacy that has fragmented bodies of knowledge, and that continues to replicate and reproduce these constructions as norms. In a small way, mending might be conceived of as a conscious intervention to stitch and meld together the binaries created from being violently separated over hundreds of years. With this awareness, it may carry the potential to de-hierarchise, reconnect, repair, care and find new paths of interdependence and relations. If practice + theory = praxis, mending might also be positioned as the +, interconnecting the two.

[Featured Image: Visible mending by Kate Sekules. All the images are courtesy of Amy Suo Wu]

| ↑1 | Donna Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial,” Feminist Studies, Vol. 14, No. 3 (Autumn, 1988) p. 575-599 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Ibid. |

| ↑3 | Teana Mammah-Boston, Cultural Diversity Minor Course Outline. Themes and Goals. Last accessed Nov 2019. https://1920.mywdka.nl/WDKCDVPRAM/minor/theme-and-goals/ |

| ↑4 | Ibid. |

| ↑5 | bell hooks, Teaching to Transgress (Great Britain: Routledge, 1994) p. 15 |

| ↑6 | Robert Bringhurst, The Elements of Typographic Style (Hartley & Marks, Publishers, 1996) p. 25 |

| ↑7 | Susanne Kuchler and Daniel Miller, ed., Clothing as Material Culture (New York: Berg, 2005) p. 21 |

Amy Suo Wu is an artist and teacher based in Rotterdam. Her practice weaves text and textile into material, political, and historical storytelling. She is the author of A Cookbook of Invisible Writing, published by Onomatopee, which explores steganographic practices as acts of protection, survival, and resistance. Over a decade she has taught across experimental and critical art and design programmes in the Netherlands, and currently teaches at ArtEZ Arnhem and the Royal Academy of Art, The Hague. Her work has been exhibited internationally. https://amysuowu.net

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)