Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

“Frieze Week” or this week in London where the bubbling art scene creates disparate situations, a variety of emotions and even the possibility of discovering some art works that lend meaning to so much posing, partying and so many expensive outfits.

The voracity with which the contemporary art market chews up increasingly young artists is, at this point, just one more feature of extremely accelerated cultural consumerism. The cycles of artists appear ever shorter, their careers beginning to seem ever more worryingly like those of athletes, destined to triumph young (in the best of cases) to later be forgotten or criticised for repeating the formula that legitimised them in the first place. This frenetic mechanism has been going round in my head during my strolls through what has come to be known as “Frieze Week”.

The success of the artist Ed Atkins (Great Britain 1982) is symptomatic. Relatively unknown until only a year ago, in this edition of the fair one has been able to see his work as part of the Frieze Film programme –with his excellent video “Delivery To The Following Recipient Failed Permanently”–, at the stand in the fair of his gallery (Cabinet), in the Tate Britain with a monographic exhibition as part of the prestigious programme Art Now and in the screening of his collaboration with Haroon Mirza and James Richards in the impeccable Chisenhale Gallery. As a coda, an image of one of his videos adorns the cover of the October issue of the magazine Frieze. Atkins is, without a doubt, one of the most exciting artists on the British scene at the moment. His videos in HD demonstrate an exceptional mastery of both editing and sound. Hypnotic and subversive, his work manifests an obsession with the corporal, with its precarious and transitory status, in the face of the artificial and the object. This decadent fascination, along with the pace of the montage and exquisite use of colour as a compositional element convert him into the post-modern child of Kenneth Anger and Paul Sharits, who decided to make videos having seen the rescued scenes from “L’Enfer”(Hell) by Henry-George Clouzot.

In the site-specific section called Frieze Projects, which this year artists such as Laure Prouvost, Christian Jankowski and Pierre Huyghe, amongst others, have participated in, the project that has caused the most commotion (with the permission of the yacht of Jankowski) has been that of the group Lucky PDF. These four artists (all born in the United Kingdom in 1986) have set up a television studio in the fair, open to the public, from where they have rehearsed and broadcast live a daily one hour programme, each of the four days that the fair has been open to the public. Opening sequences with a new age aesthetic lead onto discussions about Spinoza, a performance by a Japanese krautrock band, or to give an example, an interview in which the artist Cory Arcangel is subjected to a questionnaire, concocted for the comic actor Leslie Nielsen at the hands of a London curator, dressed up as a giant tomato (the video of this interview can be seen here).

The world of Lucky PDF is a pastiche in which theory and pop, critique and parody, co-exist on a similar plane. Something like the experience of surfing the Internet with no fixed destination transposed into a television format. And, just like Ed Atkins, during the year 2011 they have gone from relative anonymity to carry out projects and exhibitions in institutions and galleries in London, unleashing on the way, a euphoria of broadcasts made by the artists on the Internet. The only shadow in such a sunny perspective for these artists is the issue of ephemerality: what is the recipe for maintaining this point of equilibrium between creativity, credibility and relevance, when you have achieved such an incredibly rapid success?

The other big question evident in the fair–in an edition overshadowed by the political-economical tensions and the threat of a crash of the markets -was that of going for the safe bet: for established names, colour and works in 2D (painting, photography and the triumphant return of collage). Also significant was the minimal presence of videos, not to mention the disappearance of 16mm projectors, so ubiquitous in previous years.

However, despite it not having been a daring or courageous edition, there was a good number of galleries and pieces for which it was worth enduring the long hours under the neon lights, amidst the human hordes. The gallerist Elizabeth Dee hit the spot showing various video pieces by the New York artist Alex Bag –something like the “big sister” of Ryan Trecartin– and the always fantastic Adrian Piper, with a series of cut-out figures and collages made during the nineties. And it was a delight to come upon the monographic and retrospective presentation of Helena Almeida in Helga de Alvear’s stand. An impeccable installation with a fair number of her photographs and drawings – midway between the exploration of the body in space, performance and conceptual art, similar at times to pieces by Vito Acconci or Bruce McLean–, that also seduced the curators of the Tate, who acquired some pieces for the permanent collection.

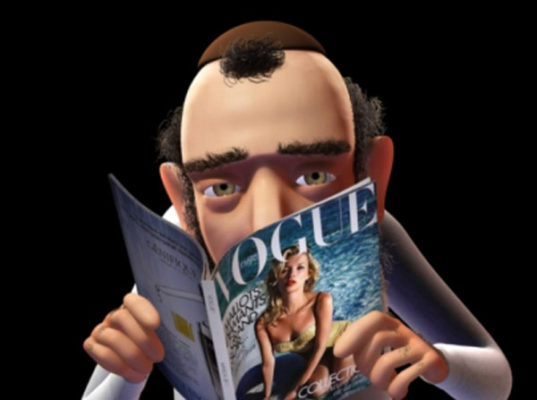

But probably the most fascinating piece in the whole fair, that I took home with me without needing to purchase it, was situated in the stand of the Berlin gallerist Johann König, who presented the new video by the artist Jordan Wolfson, “Animation, masks” (2011). In it, a 3D animation of a disturbing character called Shylock assumes the voices of different characters through various fragmented narratives that tackle the dichotomies and conflicts of the binomial love/sex. In one part, we hear a dialogue between the artist himself and a woman. Their voices and relaxed breathing seem to suggest that they are in bed and that their bodies are touching. Wolfson asks his companion to describe what it is like going to bed with him, to which she accedes with the tension and inconsistency typical of flirtation. The sensation that maybe we shouldn’t be listening to this intimate conversation, that sounds so real, becomes annulled by our own identification with the familiarity of this type of situation (loving-sexual). While this happens, the only thing we see is the face of Shylock, ever more distorted and erratic within his digital aesthetic. Shylock holds in his hand– and every now again glances through it with us– a recent copy of Vogue Paris with Kate Moss on the cover, reproduced to even the most minimal detail. The backgrounds of the screen change incessantly, showing at times bourgeois and sophisticated interiors like the ones in Vogue and humble homes with a working class and shambolic feel in others.

It is impossible to list the quantity of triggers that these layers of meaning activate in the brain of the spectator: popular culture in which we are inevitably immersed, the aspirational consumerism of fashion and design, the sinister relationship that for a few moments we have with Shylock, with his virtual corporality and his worrying changes of humour, the sexually charged conversation of the couple…All these stimuli a priori unorganised, in reality create an epistemological system, something typical of the work of Wolfson. The ventriloquist-artist and his digital doll conjure the voices of our emotional and post-Fordist schizophrenia, as well as our necessity to extract meanings to guide us through them.

For someone who is not a collector and with little perspective of becoming one, the encounter with an art piece of this calibre instantly revaluates the experience of the art fair. Because what is easiest and most common is to fall into the inherent cynicism of the art market, but under this roof and in this “contaminated” context, there are hundreds of real and sincere pieces that maybe we won’t see again. Is this not ultimately what it’s all about? Suddenly, while I walk towards the exit leaving behind the Wolfson piece, looking for a zone with zero stimuli, I think that it has been worth the effort. At least for the moment.

Lorena Muñoz-Alonso is interested in the points of friction between criticism and curating, and how productive this tension can be. She wants to communicate the discourses of contemporary art to the widest possible audience through: essays, reviews, interviews, exhibitions and webs. She collaborates with a variety of media, such as frieze and Art-Agenda, as well as artists and institutions. Her two web projects are [SelfSelector->http://selfselector.co.uk/] and [Machinic Assemblages of Desire->http://machinicassemblagesofdesire.tumblr.com/].

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)