Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Bertolt Brecht carried around with him a Bible full of annotations and images. He treated it like a notebook and had stuck on the cover the photograph of a racing car that he had cut out from a newspaper. Brecht wasn’t just the contemporary of Walter Benjamin, he also a friend of the philosopher of technical reproducibility, who stated that hence forward the work of art would be accessible to the masses and would contribute to what he called the “literaturization” of lifestyles – a concept that refers to the process of superseding the roles “author” (producer) and “reader” (consumer) to pass to what we currently call the prosumer -. In some way or other Benjamin’s theory and Brecht’s Bible don’t seem like unrelated elements to me, as what one puts into words, the other transformed into facts.

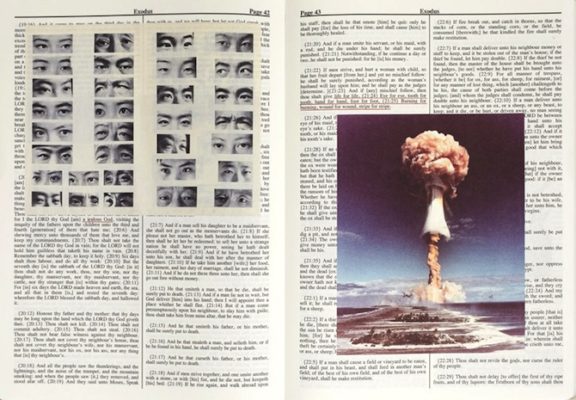

Based on this personal object of Brecht, the artists Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin have elaborated the project “Holy Bible“: a Bible illustrated with images stemming from the Archive of Modern Conflict, in London. Though they have maintained both the format and the content of the work, the images they have selected from the archive have been printed directly over the text, thereby causing fragments of it to be no longer visible, and they have underlined in red on each page some of the words that appear.

So that when we have the “Holy Bible” in our hands, the type of reading we carry out ends up being a rapid search down the page looking for a trace of red and later a glance at the image. The biblical text that isn’t underlined is ignored, so the subject we read about becomes violence. For the gesture of Broomberg and Chanarin that prohibits our access to a text, through the placing of images as if in a form of censorship, is as violent as the content of the images, where we see anonymous dead people; leaping from a boat in flames; devastated landscapes; soldiers; weapons; a child tied to a tree; a flower; blood; bodies piled on top of each other…all of which perverts a text that is, for many, sacred. To the severity of the gesture and the images one has to add the poetry -though no less violent- of the words underlined in red, that for the simple fact of being highlighted rapidly acquire a link with the image, as if those specific words had always been there, waiting for the right photograph.

In “Holy Bible” we also find a fragment of the text “Two Essays on God and Disaster”, by Adi Ophir. Titled “Divine Violence” this piece of writing by the Israeli philosopher explains that on each occasion that, according to the biblical narrative, God has presented himself to mankind, some misfortune has occurred, natural or provoked by humans, that has been justified as a divine sign. Ophir talks about the victims of calamities, the divine punishments that have been earned by failing to comply with some law that they didn’t know, as the materialization of God on Earth. If we bear in mind this condition, the work of Broomberg and Chanarin can be interpreted as a transformation of the Bible into an album of photographs that runs through some of the scenes in which a supposed God has been located on Earth through anonymous victims. “Holy Bible” is perhaps a way of settling scores with a divine figure that has been created and maintained by mankind and has served and serves to justify many barbarities.

Returning to Benjamin I think that perhaps he also referred to this type of practice, when he talked about the literaturization of lifestyles. A literaturization that in some cases will arise through violence –as in the gesture of Brecht and recently that of Broomberg and Chanarin- but which will permit the renovation perhaps ad infinitum of discourses and even of those that seemed the most sanctified.

Anna Dot was born on a Sunday in April. She is from Torelló and works between two worlds, worlds that she cannot perceive as being in any way separate: one of artistic production and one of reflection, writing about contexts of art.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)