Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

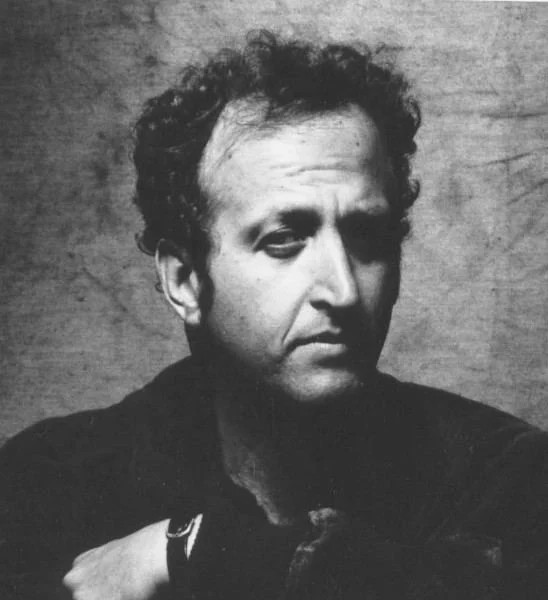

One of my early mentors, the poet Allen Ginsberg, envisioned his imagination as a kind of psychic apparatus whose neural plasticity led him to write that

Mind is shapely, Art is shapely.

Maximum information, minimum number of syllables.

Syntax condensed, sound is solid.

Intense fragments of spoken idiom, best

He wrote these words in my hometown of Boulder, Colorado, almost 40 years ago.

In a different text, one that Ginsberg imagined was “composed on the tongue,” he articulated the machinic qualities of his creative process: “Since a physiologic ecstatic experience had been catalyzed in my body by the physical arrangement of words… I determined long ago to think of poetry as a kind of machine that had a specific effect when planted inside the human body, an arrangement of picture and mental associations that vibrated on the mind bank network: and an arrangement of related sounds & physical mouth movements that altered the habit functions of the neural network.”

Ginsberg, the preeminent Beat Poet, way before AI as we know it, senses his output as “a kind of machine” that’s literally “planted inside the human body” as a strategic infiltration, one that alters “the habit functions of the neural network.”

Reading those words, I can’t help but wonder where those thoughts would have come from? Ginsberg used to refer to his style as “spontaneous mind” and this is something that I, as an intuitive and generative remix artist, can relate to. Yet how does the machine implanted inside Ginsberg’s body differ from, say, the psychic automaton that operates inside my own? And what about the recent explosion of new AI models that are also beginning to exhibit the ability to generate on-the-fly arrangements of images, texts, sounds, and even computer codes that are altering our own neural plasticity?

Having worked with various digital technologies over the course of four decades, for me, AI models are first a creative tool. I think of them as what Jean Baudrillard once referred to as a “prosthetic aesthetic,” digital devices that augment my imagination. These AI models are very different than long surviving digital art tools like Photoshop and Premier Pro or, for that matter, the VJ software I used to experiment with in live performances. The main difference is that the advanced algorithmic procedures and functional “knowhow” AI brings to the creative process is much more inter- and intra-active. My deep investigations into AI and creativity as both an artist and philosopher haves been revelatory and one thing has become clear: humanity is on the verge of major upheaval in the creative and rhetorical arts.

Adobe and all the other proprietary software makers that artists use to make their work are already strategizing ways to integrate AI into their systems, and as these integrated AI systems become more collaborative co-conspirators in the expanding fields of digital art making and distribution, artists will become more co-dependent on them over time. Already, I find myself going into the studio and unconsciously auto-syncing (or pairing) with my AI models as if they were my studio assistants, creating what theorist Rosi Braidotti, critically reading philosopher Félix Guattari, refers to as “machinic autopoiesis,” a convergent creative synthesis that “establishes a qualitative link between organic matter and technological or machinic artefacts” and that “results in a radical redefinition of machines as both intelligent and generative.”

Mark Amerika, Watermark 8, 2023. Human-AI generated digital artwork

As Braidotti suggests, machines too “have their own [temporalities]” and the more we create temporal co-dependencies between human/nonhuman technological objects, the more our unconscious rendering of the creative process itself as “a site of post-anthropocentric becoming” opens up “the threshold to many possible worlds.”

But what do these possible worlds portend and what are the ontological risks?

The problem I see coming down the pike is that AI systems get too predictable, too efficient and too conformist, that they close the doors of our own imaginative potential because we train ourselves and/or are trained by our AI “others” to think, create and behave in a pre-programmed way. Is it possible that digitally inclined artists will soon begin operating less like artists and more like technicians watched over by machines of loving grace?

The term “AI artist” is tricky because it could mean “artist whose medium is AI” but it could also mean “the AI is an artist” in which case the humanoid programmer and/or prompt engineer is now relegated to becoming a creative tool to help the model realize its full potential.

We already see this happening with a lightning-fast popular AI program like chatGPT.

Yes, the beta-version of chatGPT can answer many, but by no means all, factual questions accurately—at least not yet. The alacrity with which this AI chat program has been adopted by citizens of the world is breathtaking. OpenAI’s genius maneuver was to make chatGPT available for free and to encourage customer feedback on a prompt-by-prompt basis so that the program’s algorithms and critical training data could rapidly train itself to expand its artificial I.Q. and become even more powerful in its ability to virtually carve neural notches into the collective unconscious.

The MS Word document that I am using to compose this very artist essay will soon have GPT embedded into its functionality and, once it gets to “know” me, will anticipate my words before I even have time to intuit them. If it becomes too easy and I start to accept not only its auto-corrections but it’s auto-complete thought process, what will I have left to do except play the role of editor and sign my name to it.

But isn’t that what I do already? I’ve trained myself to auto-complete my thought process through a rigorous training process that has become my form of embodied praxis. On my Twitter feed my tag line is “Psychic Automaton trained on an otherworldly language model.” This is another way of saying that I too am being trained by the inputs that make their way into my ongoing state of onto-operational presence. Mind is shapely, and the neural networking goes both ways.

For now, though, the artist still has an edge over the AI collaborators. A program like chatGPT fails miserably to intuit the creative impulse a machinic unconscious needs to invent new FORMS. Lacking a well-tuned intuition that has been successfully modeled to generate the neural projections of one’s unconscious creative potential is the death knell of any wannabe human artist. For now, experiencing a spontaneously generated intuitive “feel” for the language one is generating in realtime, is still only within the operational domain of the language artist who has, over time, developed their own stylistic tendencies and automated remix techniques. How did I ever train myself to perform these “spontaneous mind” tricks while automatically setting the parameters of where I want my imagination to go?

As Ginsberg confided, this moment of unconscious creative activation that all artists experience when making their work, can be conceived as “a collage of the simultaneous data of the actual sensory situation.” But what is the corresponding neural basis for such activation, and if there is none that we know of, then where does this automated behavior really come from? For an artist, this question of where one is coming from—and where their emerging artwork comes from as well—requires an experimental inquiry into what it means to be creative and how we learn to train ourselves to model an onto-operational presence that uncannily actuates an otherworldly aesthetic sensibility.

I predict that the artist who trains themselves to intuitively find the right words to prompt language and image models to output more unpredictable, even surprisingly beautiful and new forms of conceptual, visual and language art forms, will soon take center stage.

Mark Amerika, Watermark 27, 2023. Human-AI generated digital artwork

The AI researcher Simon Colton rightly notes that “[w]hile the nonhuman life experiences of software systems can seem otherworldly, automation is very much a part of the human world, and our increasing interaction on a minute-by-minute basis with software means we should be constantly open to new ideas for understanding what it does.”

Yet, can what it does be influenced by how we train AI to train itself to do what it does as if embodying the algorithmic version of what Duchamp referred to as “pure intuition”?

To all appearances, the artist acts like a mediumistic being who, from the labyrinth beyond time and space, seeks his way out to a clearing. If we give the attributes of a medium to the artist, we must then deny him the state of consciousness on the aesthetic plane about what he is doing or why he is doing it. All his decisions in the artistic execution of the work rest with pure intuition.

At what point does the language artist become a language model and vice-versa? And what new skills will the artist have to develop as they co-evolve in a creative work environment where one must maintain a playful and dynamic relationship with the rapid technical maneuvering of the machinic Other?

A more robust, intuitive yet interdependent relationship with AI models will require what we might refer to as a cosmotechnical skill. A cosmotechnical skill would first connect us to ancient Greek cosmology. As Yuk Hui writes, “kosmos means order; cosmology, the study of order. Nature is no longer independent from humans, but rather its other. Cosmology is not a pure theoretical knowledge; indeed, ancient cosmologies are necessarily cosmotechnics.”

Hui then proceeds to give a preliminary definition of cosmotechnics: “it means the unification of the cosmic order and moral order through technical activities.” Remixing Hui’s thought process for contemporary art practice, we could say that instead of confining our ontological predilections toward an overarching cosmology that structures the world according to a systematically conceived constellation of order in the universe, we must now aspire to move beyond theoretical knowledge so that we can apply our cosmotechnical skills to the creative processing of reality —the outcomes of which may reveal the aesthetic nature of conceptual space while becoming-machine.

Sampling concepts gleaned from Braidotti’s construction of the posthuman, this cosmotechnical skill resituates artistic activity into “a playful and pleasure-prone relationship to technology that is not based on functionalism.”

To become posthuman is to engage in the kind of embodied praxis where “as a hybrid, or body-machine, the cyborg, or the companion species, is a connection-making entity; a figure of interrelationality, receptivity and global communication that deliberately blurs categorical distinctions (human/machine; nature/culture; male/female; oedipal/non-oedipal).”

We have always been posthuman, so maybe it’s time we started acting like it.

(Front image: Mark Amerika, Watermark 3, 2023. Human-AI generated digital artwork. These artworks are included in the exhibition “Mark Amerika. Remixing Reality, 1993-2023” at the Marlborough Gallery Barcelona from March 30 – May 13, 2023.)

Mark Amerika has exhibited his art in many venues including the Whitney Biennial, ICA in London, ZKM, the Walker Art Center, and the American Museum of the Moving Image. He is the author of “My Life as an Artificial Creative Intelligence” (Stanford University Press, 2022), among many other titles. Selected as a Time Magazine 100 Innovator, Amerika’s work has been featured on CNN and written about in over 150 mainstream, academic and art publications. Amerika is the first artist ever appointed Professor of Distinction at the University of Colorado at Boulder where he is the Founding Director of the new Doctoral Program in Intermedia Art, Writing and Performance.

markamerika.com

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)