Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Preface

Published against the backdrop of “retracted life” under the current pandemic conditions, the November issue of A*Desk presents the work of twenty contributors who interpret a general concept of “retraction” in and out of the artistic context from various vantage points in various mediums. The issue is thematically organized into five weekly installments, each introduced by a segment of a running text written by guest editor Peter Freund.

Retraction 3: Flip of a Coin

Elena Kuroda, Dissonance

Agnès Thöni, Maybe that’s why a present is called a present

Nuno Carvalho, Algorithm Composition 01

Andreas Kaufmann, Intermission Projects

Introduction (Part 3 of 5)

The flip of a coin oscillates between the heads and tails of chance and determinacy. On one side, the exact outcome appears to result from an operation free of any algorithm. On the other side, the process is strictly governed by a delimited act, calculable probability, and specifiable odds. At least since Dada, the aleatory in art has provided a means to liberate the artistic outcome from a destination defined in advance. Yet the attitude toward the random has had its own two sides. “Chance operations,” “rules of the game,” and “directives” name a few uses of algorithmic procedures that submit the performers to chance in order to bypass operational goal-seeking and to enable every outcome to become a good outcome.[1] On the other side, we find “uncreative writing” and like-minded gestures in which one rigorously submits to the laws of contingency in order to enter the volatility that lives inside the symbolic order.[2] Either way, in the extended moment of an oscillation, in the differential retraction between toss and landing, one faces and commits to the fate of one’s own blindness.

Herein lies the inexorable frame within which the work and a politics of the work become possible. Such chance, as an artist colleague put it, “advocates the ignorance of an observing, thinking subject, destabilized due to insufficient laws, clumsy observations and the weak power of calculations.”[3] The importance of enduring, if not also enjoying, one’s own stupidity and dumb luck cannot be underestimated. Too much foresight and intelligence are the enemy of the game; in fact, the rules prohibit it. The only game in town is to discover the retroactive necessity of the accident.

A number suddenly pops into the mind of some perfectly normal guy: 1734. He has no idea why but then begins to generate a string of associations relating this chance number, partly through mathematical operations, to an intricate explication of his life’s trajectory. The man notes that the span between the ages of 17 and 34 had been his most formative and best years and that he was saddened upon recently turning 34, as he considered that age to mark the end of one’s youth. He next discovers, through consulting a standard German bibliographical index, that the quotients of 1734 divided by 17 (=102) and of 102 divided by 17 (= 6) in addition to the divisibility of both 17 and 34 by 17 all yield numbers identifying specific literary and philosophical texts that reflect an undeniable meaning on the present moment in the man’s life. And the associations go on.[4] Out of this stochastic, absurdist process emerge a specific set of operations and a concrete logic that retroactively reveal within a random event (here a chance number) the fragments of a knowledge strangely unbeknownst to the person who knows it.

Moving along a related continuum but in the opposition direction, a contemporary philosopher has famously reinterpreted the quintessential poem on chance, Un Coup de Dés Jamais N’Abolira Le Hasard (1897/8). He argues that the text, which abruptly breaks with the poet’s own metrical practice, instead of giving way to the anarchic gesture of “free verse,” introduces a new form of metricity based on numerical encryption, using the numbers 7, 12, and 707.[5] In a parallel vein, a conceptualist redaction of the same poem (1969) covers each line of the original with black rectangular horizontal bars. The retraction foregrounds the precise spatial configuration of the words scattered like dice across the page, underscores the original poem’s presentation of the letter – the purity and limit of the arbitrary linguistic medium – as already overrun by its own visual image, and establishes a score for a performance of the original text.[6]

This week we present four works. First, imagine a set of flickering lights about to go out, discovered by chance and plotted as points within a major European city – a global financial center – in distant public spaces over a period of four years. The lights persist in a conceptual state of oscillation in relation to themselves and each other across space and time. As such, they map the terrain of the city like a self-erasing sketch. Second, we find a harmonograph, a hand-built drawing machine designed to produce highly regular, geometric figures through the harmonic motion of oscillating pendulums. Into the machine’s ostensibly natural movements, the artist introduces subtle, arbitrary perturbations from the environment, ranging from slight nudges to steps on wobbly floorboards, that dislocate the reassuring internal order of probability. Third, a sculptural assemblage caricatures today’s recombinatory utopia of absolute openness and the probability on which this fantasy hinges in a series of works that has already been halted at the first assemblage. Finally, consider the oscillation that delineates the art proposal as a writing genre and gesture. The proposal expands or retracts action based on the outcome: if accepted, you go forward; if not, you go back, maybe try again, or maybe change or drop the idea altogether. But imagine then three proposals that are retracted in advance. These works, like all artist proposals, are constructed like Schrödinger’s quantum cat box, which contains a feline that is at the same time alive and dead.[7] The artist of these proposals sees no need to open his boxes – that is, has no interest in their juried consideration and external outcome – but simply constructs and leaves these proposals floating in a conceptual state of superposition.[8] Years later (2020), the artist adds a fourth piece, a rejoinder that retracts the triptych of decisive non-starters, situated in the recent pandemic lockdown. In the universe of this supplemental piece, the observer is no longer positioned outside the contraption’s uncertainty but becomes the cat inside facing the inescapable specter of being simultaneously dead and alive.

Peter Freund

Notes

[1] The references here are to the algorithmic works of Sophie Calle, John Cage, Fluxus, and Goat Island. See also La Monte Young & Jackson Mac Low, An Anthology of Chance Operations (New York: Young & Mac Low), 1963.

[2] Kenneth Goldsmith, Uncreative Writing: Managing Language in the Digital Age (New York: Columbia University Press), 2011. Craig Dworkin and Kenneth Goldsmith, Against Expression: An Anthology of Conceptual Writing(Chicago: Northwestern University Press), 2011. Here one finds fruitful overlaps in a retractive vein between the legacies of Oulipo and conceptual art.

[3] Eloi Puig, “Reordering Torvix” in Peter Freund, “Retracted Cinema,” forthcoming article in Found Footage Magazine (2021).

[4] Sigmund Freud, The Psychopathology of Everyday Life, trans. Brill (New York: The MacMillan Company), 1914, ch. 12.

[5] Quentin Meillassoux, The Number and the Siren: A Decipherment of Mallarmé’s Coup De Dés (Faimouth, UK: Urbanomic), 2012. Also see Quentin Meillassoux, “The Materialist Divinization of the Hypothesis.” Lecture delivered and recorded 2012 at the Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York City, video.

[6] The reference here is to Marcel Broodthaers’ 1969 intervention (mechanical engraving and paint on twelve aluminum plates) into Stéphane Mallarmé’s Un Coup de Dés Jamais N’Abolira Le Hasard. In this work one might find an extension of Edmond Jabès’ aphorism: “Render the word visible, that is to say, black.”

[7] The idea of “superposition” in quantum mechanics posits that a quantum exists in two opposite physical states simultaneously. “Schrödinger’s Cat” was a 1935 thought experiment devised by physicist Erwin Schrödinger to critique the “Copenhagen interpretation” of the phenomenon by raising the question of when and how the superposition of the two states is resolved into one state or the other. In Schrödinger’s tale, a cat both dead andalive lies in a sealed box set up with special conditions of observation that will determine the cat’s ultimate fate.

[8] These works should be distinguished from the quixotic proposals (e.g. the Alter series) of Lim Tzay Chuen who wishes to set off a series of bureaucratic rationalizations for rejecting the most well-reasoned of outrageous proposals. On the other hand, these works also need to be differentiated from a project like Duchamp’s anticipated painting Tulip Hysteria Co-ordinating, which simply never arrived at the 1917 “First Annual Exhibition” of the Society of Independent Artists. In a related vein, the concept differs from the surprise delivery of Rauschenberg’s Portrait of Iris Clert.

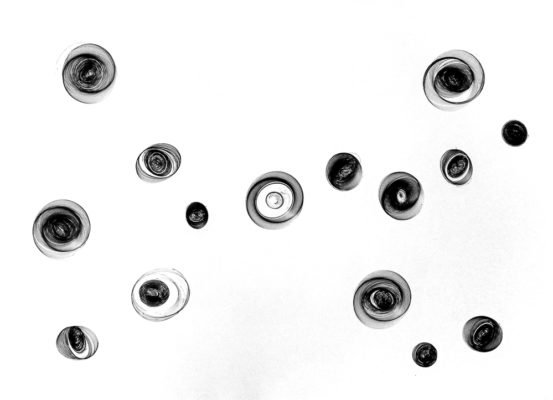

[Featured Image: Elena Kuroda, Dissonances]

Elena Kuroda

Dissonance, 2018-Present

Harmonograph: Wood, metal and plexiglass

Dimensions variable

Drawings, ink on paper

Dissonance, 2018-Present

Video, 2 min 44 sec loop

Statement

My work generally focuses on depicting the passage of time within the banalities of life through a series of multiple photographic images and drawings. The subject matter ranges from objects, people, memories, places of encounters, and its environments. I search for a certain order within the context of the subject matter that allows a transformation from the ordinary and predictable into a liberated complex system that is “honored” and given its space allowing it to be seen in novel ways. In this transformation, time often becomes an essential factor that needs representation.

With the intent of looking beyond the obvious within my obsession with time, my recent work has been inspired by the “unseen.” My interest is to be able to perceive and visualize what can only be achieved by sensorial experience. Evident in the series Dissonance, the work departs from the use of photography to explore more intricate random patterns and trajectories delivered from drawings that represent vibrational sound waves. I use a self-built mechanical semi-automated instrument to create the images. Through these drawings I question the function of chance and probability by means of a premeditated and arbitrary intervention into the image production. I am able to witness a contraction in a trajectory and time, shown on the paper as an entry point, the past, and an exit halting point, the present.

By contemplating the present, the stillness, it becomes perceptible that structure cannot exist without chaos. On the contrary, in the present, I feel we are moving forward in time at an accelerated rate. I wonder if by stopping and contemplating the present as it is and accepting its nature, some sort of order will emerge from chaos, eventually returning us to an existential understanding that frees us from its construct.

Elena Kuroda (b. 1977) is a Spanish and Japanese artist. Born in Madrid and raised in Japan, she studied photography in Los Angeles (USA) where she worked for several years in the field while exhibiting her work in various galleries. Upon her return to Spain, she has continued showing her work and has been working as a freelance photographer. She uses photographs and drawings as a primary medium with the occasional use of video work in installations. Elena currently lives and works in Barcelona. elenakuroda.com

Agnès Thöni

Maybe that’s why a present is called a present, 2016-20

Video, 10 min 32 sec

Statement

The video work is based on flickering lights collected between 2016 and 2019 in the city of Zurich. They all were recorded during a time span of one minute, documenting their vacillation between staying or going out. Echoing this erratic movement, the sound of their surroundings blinks on and off as well. A timestamp relates the luminaries and their exceptional state to a date and a time. Flicking luminaries in the city of Zurich are actually rather scarce. They belong somehow to the backside of the city, which stays most of the time hidden behind the city’s clean and orderly appearance. They are in a way “retracted material”, the folded parts of an amorphous mass that could be our civilisation. Some folded parts are as superficial as just dysfunctioning lights, and others are much deeper, ranging from negligence to loss of control to barbarism.

Agnès Thöni is a Swiss and Spanish artist currently based in Zurich. Originally trained as an architect at the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya and the Technische Universität Berlin, she started her artistic practice after her studies in 2011. In 2016 she stayed in New York City for an artistic residency. She has shown her work in Spain, Switzerland, the U.K., Austria and the United States. Due to her background, her artistic practice has often a strong relation to geometry and architectural elements. They comprise several media such as video works, room installations, performances and sculptural objects, and often feature an analytical, exploratory component. The works originate in a question or an intuitive thought and materialize in the form of a visual answer or reaction to it.

Nuno Carvalho

Composición algorítmica 01, 2020.

Wood, paper, metal (brass), glass, basketball.

Installation, variable dimensions

A paused series of material recombinations becomes a receptacle with the aim of connecting the present with history in a continuous state of change.

Statement

Starting from the premise of “Retraction,” the work Algorithm Composition 01 proposes to present a fluctuating narrative between the artist’s imagination, his critical position on the current world and the algorithm as probability of the observation sequence from the instant of time. The resulting work aims to explore artistic processes where the artist intends to minimize the gesture on the results. The materials used are intended to reflect the proposed concept, mixing and contrasting elements generated by human activity to create installations that will have sculpture as a resource.

Nuno Carvalho (1978), a Portuguese artist living in Barcelona, has been developing artistic proposals in the field of installation, sculpture and performance in the last decade. Nuno Carvalho is a multidisciplinary artist. In his pieces, the public space, objects, actions, time and his body are the main elements. His work fuses the different artistic disciplines and languages freely within the same piece, using the immediacy of the snapshot and live action to create situations that raise philosophical questions and poetic experiences reflecting the subtle contradictions of contemporary reality that often turn into a comical and absurd critique of the most immediate reality.

Andreas M. Kaufmann

Intermission Projects, 1984-ongoing

The “Intermission Projects” or “Pausenprojekte” (in German) deal with issues related to the public sphere and/or public space. They are potential artworks; they have no claim to be realized. On the contrary, they pretend they have already been executed at a specific site. Actually, the truth is that they exist only as more or less perfect simulations, they aim to look like a photo- or video-graphic documentation – just as though it were like that.

Bilderpause, 1996/2000

Photo simulations

In this “Image Intermission,” the urban realm is no longer a site of identity-giving communal experience, but the arena for delirious consumerism with a narcotic effect on the masses. Anything that interferes with this purpose of movements in public is unwelcome. This is the point at which “Bilderpause”, my proposed intervention of “deleting” all the signs in a commercial street, sets in.

Denkpause, 1984/1999

Photo simulations

This “Thinking Intermission” deals with the idea that the traffic has to wait until the ice is melted.

Lichtpause, 2004

Video, 3 min 28 sec

This “Light Intermission” shows a choreographed darkening of a city (Duisburg).

Test Human Intermission, 2020

Video, 14 min 36 sec

The picture of a feeling – something we feel, but we don’t see in the end. (The Music is composed and produced by Oliver Frank (D) / Artist name: “Oeler”). The street cinema in the video shows a fragmented re-montage of “No Country for Old Men” (Coen Brothers).

Andreas M. Kaufmann Born in Zürich, now living and working in Barcelona and Cologne. As a child I collected all sorts of things, especially fossils; and I wanted to be an archaeologist. During the last years of high school, I changed my mind. I studied Fine Arts at the Kunstakademie Münster and Photographic Design at the University of Applied Science in Münster and Dortmund. Besides, I also read Philosophy, History and German Literature at the Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster. My works have been exhibited internationally in institutions and art fairs such as the Bunkier Sztuki Kraków, Museum of Modern Art Saitama in Urawa City, Sagacho Exhibit Space in Tokyo, Apex Art in New York, Wilhelm Lehmbruck Museum Duisburg, Architecture Biennale Venice, Galerie für Zeitgenössische Kunst Leipzig….

A central aspect of my artistic practice is the fact that I have been collecting images for almost 20 years. They are mostly publicly accessible images, such as from print media, TV, archives, the www and other sources. Those images have been the material for many of my artworks, which I have realized in various techniques. The fact that these images are often part of our collective memory motivated me to explore the connection between the public sphere, images and human identity.

Peter Freund is usually working on something else. He writes to avoid making art and makes art to avoid writing. He is a sometimes curator so as to avoid his own work, but usually that inspires him to write or make art. [www.peterfreund.art] Originally from the San Francisco Bay Area (USA), Peter moved to Barcelona in 2018 on an extended leave of absence from his post as Professor of Art at Saint Mary’s College of California. In 2018-19 he had a research residency with the Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art (MACBA_CED) and a studio residency with the Werner Thöni Artspace. His curatorial project, Retracted Cinema, was presented at Xcèntric (CCCB) in September 2020 and will be followed by a forthcoming article about the program in Found Footage Magazine in 2021. Peter is a visiting artist with the Faculty of Fine Arts at the University of Barcelona, 2018-Present, and a founding member of the Barcelona-based artist collective, Adversorecto, 2020.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)