Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

We’ve got a problem with sex. Instead of considering it just another aspect of life, something natural, the object of enjoyment, communication and intimacy, for society today sex is a taboo or rather an element susceptible to be exploited commercially. Repression and/or exploitation. This is why it is so important and necessary to vindicate it, be it from LGBT stances as much as from a heterosexuality critical of the neo-liberal present.

1000 m2 of desire. Architecture and sexuality is an exhibition curated by Rosa Ferré and Adélaide de Caters for the CCCB, that proposes a journey through different moments in history when architecture has born in mind specific spaces for desire. And in this research presences are as important as absences. The strong presence in the 18th century and the absence in the 19th century leave well portrayed the spirit of the times. They also highlight the precision of the curators when clearly marking out the object of their study, leaving aside, for example, the subject of prostitution that would have opened up multiple parallel routes for investigation.

One of the great successes of the exhibition is the highlighting, the underlining of specific moments pertinent to be reread from our contemporaneity. Now that through critical theory, political activism and architecture unfinished and re-appropriated urban spaces are discussed, it is fundamental to revise (or discover for the first time) Fourier and the Situationists. Therefore, the value of this curatorial work doesn’t lie solely in the historical gaze or the establishing of genealogies so much as, above all, in its relevance today, in the possibility of considering proposals from the past to be able to rethink what type of space and society we want to build.

In an exhibition that has architecture as its principal axis, the architecture of the exhibition itself, designed by Sabine Theunissen (habitual collaborator of William Kentridge in his operatic projects) is one of its attractions, creating sections and spaces that generate a pathway full of surprises and delights, for the spatial design as much as for the documents, images and references that appear.

“To think about sex is the greatest and perhaps only real pleasure for all mortals”, wrote Jeremy Bentham in 1785, the same man who defended the theory of utilitarianism but who also didn’t publish in his lifetime the majority of the texts in which he defended sexual freedom, female emancipation and the decriminalization of homosexuality. Bentham, the creator of the Panopticon, the space of control par excellence, that in the thick of the 21st century is a good image of the technological society and big data. But before reaching Matrix, the Panopticon was also picked up on in the imagined architectures of Claude-Nicolas Ledoux or the meeting rooms of the castle of Silling featured in the The 120 Days of Sodomy by the Marquis de Sade. Because spaces typify practices and define roles. In the 19th century when the social dimension of sexuality is regulated by the church or medical science, Charles Fourier invents architecture that take into consideration passions and contribute to collective emancipation. They are the Phalanstères, where sexuality is integrated into the life of the collective in a harmonic and regulated manner; there is no repression because there is no guilt, there is neither monogamy nor adultery, and there are erotic volunteers practicing charitable love. His proposals are implemented in the covered galleries of the Louvre and the Palais-Royal, later eliminated with Haussmann’s urban reforms

Utopias and social democratization were recuperated by the counter-culture movements of the 60s and 70s, by communities such as Drop City en Colorado, the first rural hippy commune, a DIY proposal that included the geodesic domes of Buckminster Fuller, that are linked to a whole genealogy of architecture and design projects from those same years by Archigram, Ettore Sottsass or Nicolas Schöffer, an artist whose critical and historiographical recuperation is vindicated by the exhibition. Utopia, counter-culture, a need to rethink, to go against establishment…How important it is to revise our most recent history to see ourselves reflected in it and be able to reconsider the present in a critical way!

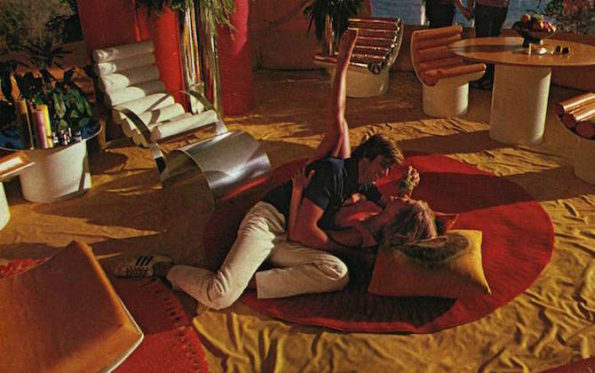

1000 m2 of desirehas brilliant moments, like the incorporation of the investigations of the architectural historian and professor at Princeton University, Beatriz Colomina into the role of modern architecture in the magazine Playboy. We already reflected on it in the article dedicated to her work but now in the CCCB it’s not just a case of mentioning the bed-office of Heffner, so much as being able to see it or even touch it. And in relation to sex, the architecture in Playboy is introduced as an element of seduction, like thePlayboy bachelor’s apartment, moving to a true sexualisation of architecture that goes beyond interiors to act as preceptors, pointing to examples of modern architecture that would fit in with this style of life. And clearly, it is not by chance that Sean Connery suddenly appears as James Bond with a couple of girls with whom he carries out a game of seduction and a choreographed struggle in the Elrod house. And this leads us to think about how in the most contemporary James Bond (that of Daniel Craig), architecture is a hidden place, isolated and totally technologized (abandoned and inaccessible basements that house the offices of the secret services or large complexes in the middle of distant deserts). But this is the object of another study…

And we come to the present day. What place does sex occupy in architecture, apart from the phallic forms that have dominated the collective imaginary from the beginning of time? Contemporary fantasies are fragmentary like our present (and it is perhaps in this section that the exhibition loses precision). There are occupied spaces, theme parks for love in which everything is regulated, dark rooms that are disappearing at the pace the world of applications for contacts grows and there are clubs in which the combination of space-light-sound generate the displacement of sex for an equivalent collective experience. Magnificent, certainly, the catalogue text in which Pol Esteve studies this phenomenon born in the Paradise Garage of New York that continues to our days. Above all there is a lot of virtual sex, aseptic and distant, and safe relations. There are also lies, the possibility of inventing new identities and the risks and new moral dilemmas that this leads to. Are we responsible for our acts in the virtual world? Recently, the excellent piece El Inframundo touched on these issues at the Teatre Lliure, and incidentally, counted on a marvellous scenography by Alejandro Andújar by way of transparent spaces that represented the real and virtual world.

The question that underlies all these examples are the questions they raise about the role which sex has played at each moment, the importance that it has been given and the place it has occupied in the public sphere, through thinkers, architects and governments who have considered it. And also the role that the powers that be consider it ought to play now, as an element that must be controlled so as not to escape the schema of production and consumption that govern our present.

Montse Badia has never liked standing still, so she has always thought about travelling, entering into relation with other contexts, distancing herself, to be able to think more clearly about the world. The critique of art and curating have been a way of putting into practice her conviction about the need for critical thought, for idiosyncrasies and individual stances. How, if not, can we question the standardisation to which we are being subjected?

www.montsebadia.net

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)