Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

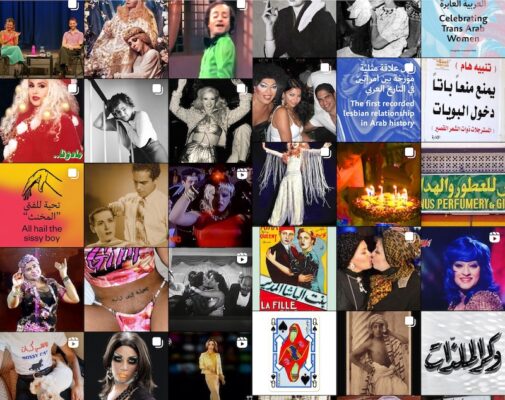

In 2019, London-based Lebanese graphic designer Marwan Kaabour launched the Instagram page Takweer, which he described as being dedicated to “queer narratives in Arab history and culture.” The amateur archive of historical traces and pop cultural curiosities that lend themselves to queer readings and interpretations has amassed 25,100 followers to date, growing into a beloved space for queer Arabs from across the Middle East and its diaspora to engage with and share elements of their history and culture that have tickled their queer sensibilities, or which they have recognised themselves in, collectively chipping away at the belief, hegemonic in both the West and the Middle East, that the Arab world has not, cannot, and will not, accommodate anything other than what today constitute normative and natural norms of gender and sexuality in the region.

In narrating the genesis of his project, Kaabour has explained that its name derives from the 81st Surah of the Quran, Surat At-Takwir, which identifies the omens that signal the imminence of the day of judgment. The word takwir itself derives from the Arabic word qura, or sphere, translating into ‘the turning into a sphere,’ which Kaabour likes to interpret as “to make a world” (Jahshan 2023). The word also sounds like the English ‘queer’. Kaabour fuses the English and the Arabic to create the portmanteau Takweer, which he translates as “to make queer” (Jahshan 2023).

I am interested in thinking with this notion of ‘making’ rather than demonstrating; of approaching a project like Takweer as a mode of queer world-making, rather than as an attempt at unearthing or authenticating queerness vis-a-vis Arabness. The purpose of a project like Takweer is not so much to locate the queer within the Arab world and to delineate an ‘authentic’ mode of being Arab and queer, but to queer the Arab world itself and to challenge the Western origin story when it comes to queerness, destabilising our understanding of who is and what is queer, and who is and what is Arab. What might it mean to route a queer gaze through the Arab world? What might it mean to learn queerness as a mode of being and becoming, as an orientation in and towards the world, from and through rather than against and without, Arabness?

In terms of the genres of content that appear on Takweer, they exist to serve three arguments: that “queerness” has always existed in the Arab world; that the Arab world had a historically ambivalent relationship to gender and sexual non-normativity, which created room for manoeuvre when it came to gendered and sexualised expression; and that Arab culture itself is characterised by a camp sensibility at odds with its professed heteronormativity. The page began as a repository of cultural artefacts that had shaped Kaabour’s own relationship to queerness at the intersection of Arabness, and which compelled him to begin a journey of historical exploration in search of queer ancestors, starting first with taken for granted but marginalised and uninterrogated popular historical knowledge he had been exposed to growing up in Lebanon, and moving on to a search for and engagement with scholarly material, as well as historical print and photographic media. As the page developed a following, Kaabour was guided in his searches by his audience.

By way of an example, in a post titled “The Fascinating Life of Iraq’s Trans Folk Singer”, Kaabour presents Masoud El Amaratly, an Iraqi singer he tells us rose to fame in the 1920s and was known for his distinctive voice and the rural folk songs he sang. Like many of Takweer’s posts, it is brief. We do not get a detailed a narrative about El Amaratly’s gender journey or even his understanding of his gender identity, and what his becoming entailed or how it was received. Instead, we get snippets pieced together from a variety of unnamed sources that offer a glimpse into the existence of a ‘trans’ subject who not only existed in the region but seems to have perhaps thrived to some extend within its regional music scene. Such narratives are often presented without much accompanying commentary, leaving it to the audience to make of it what they will, to speculatively fill in the gaps and imagine how figures like El Amaratly moved through space and time.

Kaabour acknowledged during our conversation that El Amaratly was received in what appears to be an ambivalent manner that enabled contradictory approaches to his gender identity. He emerges as a celebrated folk singer whose talent enabled his gender to be perhaps tolerated or ignored. Kaabour doesn’t present this ambivalence to his audience on his Instagram page. Rather, he presents them simply with the fact of El Amaratly’s existence, and of his positive reception as a folk singer. This, in many ways, is enough, as the existence of a regionally popular gender variant folk singer in the contemporary Middle East would feel, for many, impossible to imagine today. El Amaratly is a trace of something in the past that queer Arabs are told in the present cannot exist. Importantly, he’s a trace of transness and queerness from the early twentieth century, when anti-colonial sentiment and struggle surged throughout the region, destabilising the distinction between pre-colonial gender and sexual non-normativity and the argument that the colonial encounter resulted in the erasure of alternative modes of embodying and practicing non-normative gender and sexuality.

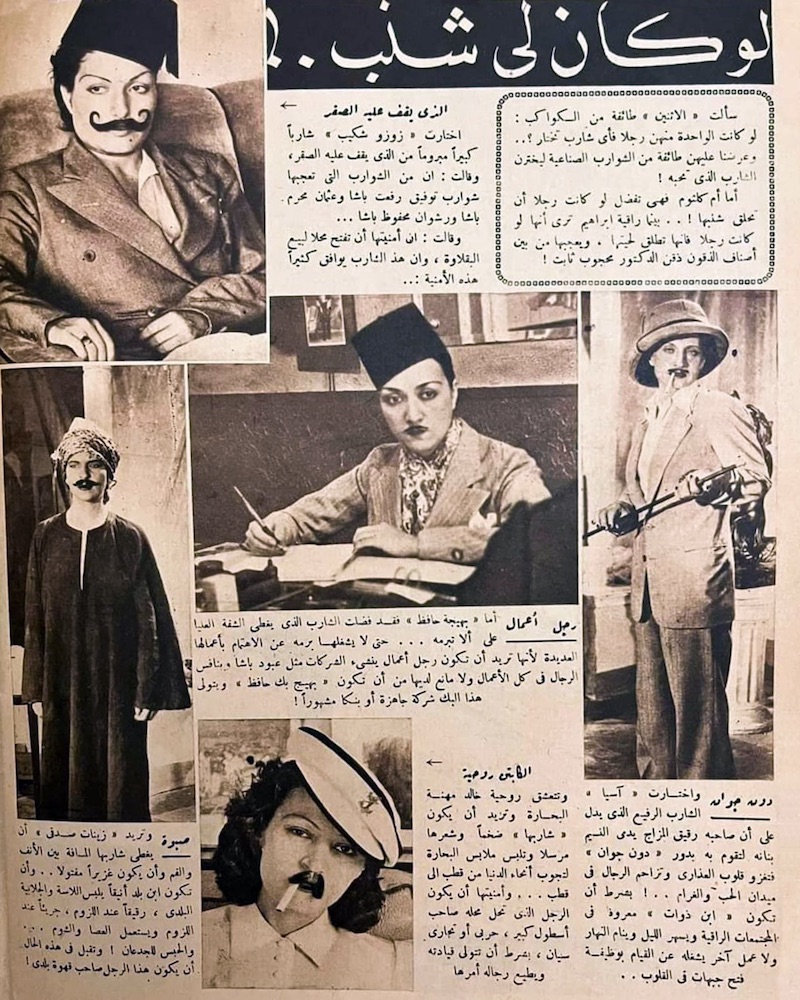

In 1942, for example, the popular Egyptian magazine al-Ithnayn wa-l-Dunya published an article titled “If I Had a Moustache,” in which several actresses were asked what moustache they would choose for themselves were they men. In 1944, the also popular weekly Al-Musawar featured a photo series of Egyptian actors and actresses cross-dressing and posing with one another. Images from both pieces appear on Takweer. From the series from Al-Musawar, Kaabour shares a photo of famed Egyptian comedian Ismail Yassin in women’s attire, being helped off a bus by dancer and actress Gamalat Hassan dressed in a suit and tarboush. According to Kaabour, the caption in the original series reads, “in unparalleled grace, Ismail Yassin attempts to get off the bus, while Gamalat Hassan preceded him and took his hand to support him for fear of falling.”

To the moustachioed actresses one commenter responds: “Arab women invented drag kings.” To the photo from the Al-Musawar series, one commenter responds by asserting that famed Egyptian writer Tawfiq al-Hakeem “is queer”. Kaabour told me that al-Hakeem had published a letter in a previous issue of Al-Musawar, calling for actors to swap clothes, to which the magazine responded by organising the above mentioned series. With regards to the commenter on al-Hakeem’s sexuality, Kaabour asked them to elaborate, to which they responded by saying they “don’t really have proof,” but explained that in the published collection of his personal letters, Zahrat Al Omer, the exchanges between him and his best friend Andre read like he “was very emotionally attached to Andre in a way that felt intimate and vulnerable.” Kaabour responded to this by saying that when he read al-Hakeem’s call for gender swapping in the magazine, he “was almost certain such words wouldn’t come out of a non-queer man.” These posts paint a picture of an Arab world in which a practice like cross-dressing was not only tolerated but encouraged.

These posts and the sentiments they elicit disrupt the teleology of queerness as it is conventionally understood, and the notion of its foreignness to the Arab world, hence the declaration that the women featured in Al-Musawar “invented drag kings.” The comments about al-Hakeem point to a speculative engagement with the possible role that queer people have played in shaping the Arab popular culture canon – about the queer figures behind the scenes introducing gendered play into the mainstream.

The material in these posts intimates a mainstream Arab interest in gendered fluidity and sexual openness that directly challenges the rigid conception of gender roles, performances, and embodiments many contemporary queer Arabs have grown up with. They lead, in the case of al-Hakeem, to a speculation about the existence of queer ancestors able to thrive, even if in secret, in a time perceived from the vantage point of the present as more flexible, during which they even potentially intervened within hegemonic culture, taking advantage of its apparent curiosities to carve out a space for queer expression right under the nose of straightness.

Kaabour has said that “if there’s one thing to take from a project like Takweer, it’s that queer Arabs have always existed: no matter what Arab authorities, media, and families who claim that queerness is a ‘Western import’ might think. Hopefully, by bringing together so many queer Arabic stories from across the decades, the page can help remind people of a time when there was more openness to difference” (Jahshan 2023). Kaabour invites his audience to engage the past in a manner that engenders a longing for the simultaneously familiar and unfamiliar, for that which has been framed as impossible, asking what this might mean for the queer Arab present and future for those who have been told that they must accept a fragmented or inadequate life at home, where their queerness is unacceptable and must be hidden away if not abandoned altogether, or a fractional life abroad, where their rejection of Arabness is framed as the condition for their being folded into so-called queer safety in the West.

Sophie Chamas is Senior Lecturer in Gender Studies at School of Oriental and African Studies, SOAS, University of London. Their research focuses on the radical political imagination in the Middle East and its diaspora.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)