Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Culture is currently trapped in a paradox. On the one hand, the dismantling of cultural policies is accelerating by means of cuts in public funding. On the other hand, cultural policies are now a battleground between a progressive left which, at its extreme, leads to repressive wokeness and a conservative right which, at its extreme, embraces a technological alt-right. Both sides seek to use culture to strengthen their ideologies and both sides are equally responsible for budget cuts.

How can we explain this paradoxical situation without resorting to theories of government austerity? How can we go beyond the critique of the spectacle-making of the arts which determines that the economic future of cultural institutions must become part of the private entertainment industry?

While the critique formulated by Debord (and developed by art historians such as Stallabras, Kleine-Benne, Bishop, Bourriand, et al) is useful to understand why exhibitions are conceived as “experiences” for cultural consumption and why the art market is increasingly filled with naive actors and speculators, Debord’s critique fails to address something deeper, namely, the loss of culture at the core of politics.

The political significance of culture persists although today it manifests itself primarily in specific gestures. The liberal left promotes the restitution of works and exhibitions critical of the formation of collections, applying postcolonial theories to project a global cultural identity in line with (neo)liberal expectations. The right, on the other hand, seeks to reinforce national historical symbols by supporting the dissemination of contemporary art with a national image, utilizing exhibitions in museums, art fairs, and other spaces of local and international visibility. Both, however, do so in a fragmented and utilitarian manner.

Meanwhile, countries like the United States (which dismantled Voice of America) and Germany (whose last Green-Liberal government closed Goethe-Institut branches) are reducing the infrastructure that sustained these long-term policies. These actions, carried out by the executive branch and with the consent of the legislative system, reveal the erosion of an internal relationship in which art and culture were strategic instruments for governments, both in domestic and foreign policy. This erosion implies the end of a continuous and uninterrupted history that had developed over the past two centuries.

During the 19th century, international exhibitions became platforms for countries to showcase not only their industrial and technological power, but also their cultural and artistic production. These art fairs were showcases in which nations built an image of their national identity through art.

Governments carefully selected works of art, often organizing national committees to choose that which best represented the aesthetic and cultural achievements of the region. This included everything from painting and sculpture to decorative objects and craft designs. They were also used to promote local styles or traditions, such as the use of specific materials, regional techniques, and cultural motifs.

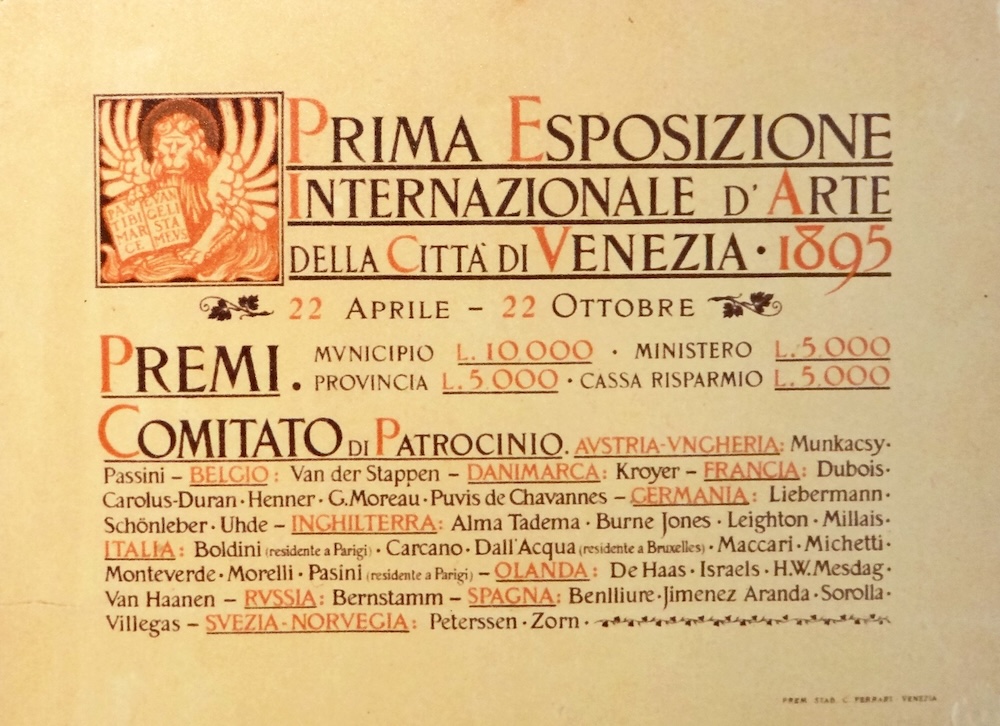

Poster for the first international art exhibition in Venice in 1895. Author: Jean-Pierre Dalbéra, Paris, Creative Commons

The Venice Biennale is a direct descendant of the 19th-century World Fairs and European international art exhibitions. Its first edition was held in 1895 and was called the Prima Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte di Venezia, with the aim of revitalizing Venice’s cultural appeal.

In the essay “Layers of Exhibition”, the authors discuss how the Biennale functioned as a space where nations negotiated their cultural identity in an international context,[1]Hossain, Annika; Bódi, Kinga; Ghiu, Daria (2011): Layers of Exhibition. The Venice Biennale and Comparative Art Historical Writing. In: kunsttexte.de/ostblick, Nº 2, 2011, pp. 1–6. Available at: … Continue reading utilizing the dynamics of competition inherent in the capitalist structures of the Western art system.

During the Cold War, governments (including China) increased their interest and investment in contemporary art as a tool to expand their geopolitical influence and strengthen national unity. Major exhibitions, such as Documenta, utilized significant public resources to project a new image of post-war Germany.

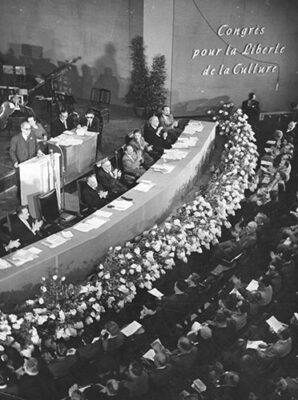

On the international stage, one of the most notable cases was the CIA’s promotion of Abstract Expressionism which it used as an instrument of cultural propaganda to showcase the supremacy of American creative freedom over rigid and propagandistic Soviet socialist realism. Although the agency did not directly fund artists, it channeled support through front organizations such as the Congress for Cultural Freedom, backing international exhibitions, publications, and critics sympathetic to this movement.

During the 1970s, culture and the arts were an integral part of domestic diplomacy. Recently-deceased former President Jimmy Carter envisioned music as a soft power [2]The term soft power was coined by American political scientist Joseph S. Nye, who defined it as “the ability to obtain desired results through attraction rather than coercion or payment.” Areas … Continue reading capable of uniting the American people across social, political, and racial lines. During his presidential term (1977–1981), Carter invited a variety musicians from different genres, from classical music and jazz to country, gospel, and pop, to the White House, thus reflecting his intention to represent the country’s cultural diversity.

Fifty years later, we find ourselves in a state of imbalance that is undermining what was considered an intrinsic relationship between politics and culture. This decline began in the 1980s with the marginalization of the arts from political agendas with a discourse that framed culture as an industrial sector.

This simultaneous erosion of politics and culture has turned the cultural industries into a system that, far from providing stability, instead consolidates structural precariousness. Artists and cultural agents are trapped in short-term funding cycles that make long-term planning impossible and reduce their margin of independence. At the same time, this model has led to the concentration of scarce public resources amongst a few actors and the conversion of public funds into private profits, thus fostering “white-collar” corruption that includes official curators acting as art advisors for private collections, committee members who “donate” art work with cross-interests, and favoring the purchase from artists in whom they maintain a financial stake.

Although the symbolic capital of culture continues to operate, as evidenced by gentrification, its use as a simple gesture to mark an ideological position has generated disappointment and anger among cultural agents, turning them into unwitting protagonists of the paradoxes of contemporary cultural life. We have witnessed the territorial expansion of biennials and the production of commissioned works at the same time as housing and work spaces become scarce; art works that fetch millions of dollars in a context of growing poverty; silent censorship and bureaucracy that delays payments; media restorations that end up in private hands; and museums that program exhibitions focused on influencers and entertainment figures.

[Featured Image: The inaugural (and notably well-funded by the CIA) session of the Congress for Cultural Freedom in Berlin, 1950. Source: Original held at the Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library, Series V, Box 1, Folder 1.]

| ↑1 | Hossain, Annika; Bódi, Kinga; Ghiu, Daria (2011): Layers of Exhibition. The Venice Biennale and Comparative Art Historical Writing. In: kunsttexte.de/ostblick, Nº 2, 2011, pp. 1–6. Available at: www.kunsttexte.de/ostblick |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The term soft power was coined by American political scientist Joseph S. Nye, who defined it as “the ability to obtain desired results through attraction rather than coercion or payment.” Areas such as cultural diplomacy, international relations, nation branding, art, film, fashion, and other forms of non-coercive global influence are primary sources of attraction, effective in seducing people from other countries. Nye, Joseph S. (2017). Soft Power: The Origins and Political Progress of a Concept. Palgrave Communications, 3, Article number: 17008. |

Jorge Sanguino, born in Cali, Colombia, is a curator and gallerist based in Düsseldorf, Germany. He holds a Philosophy degree from Universidad Javeriana in Bogotá and a Master’s in History of Art and Image from Humboldt University, Berlin, specializing in photography and contemporary Latin American art. Currently pursuing his doctorate at the University of Cologne, his research focuses on Mexican art in the 1990s. He also serves on the board of Zadik, supporting German and international art market research. He is currently advising Prof. Buchholz (Northwestern Uni) in her research on the Mexican art market. In 2016, Sanguino co-founded wildpalms with Alexandra Meffert. Sanguino contributes regularly to Esfera Pública and Artishock. (Photo: Zadi)

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)