Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

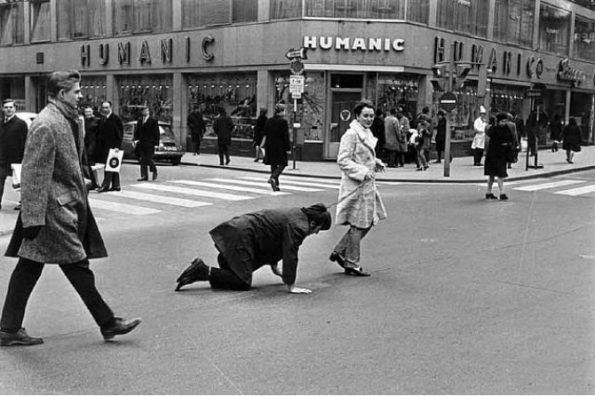

Thanks to a short review by Martí Manena short review by Martí Manen published in this very journal, I was drawn to read The Family Fang, by Kevin Wilson, a book pertaining to an increasingly rich genre of novels dedicated to art, of which Iván de la Nuez has given a good account . The work narrates effectively, and with a sense of humour, the adventures of Caleb and Camille Fang, a pair of performers who acquire a certain fame by carrying out actions in public spaces, the aim of which being to alter the normal course of events. The protagonists in the novel are specialists in creating absurd situations that provoke discomfort, surprise and unease in people that by chance become involved in them, without even being aware that they are participating in “artistic” projects. Following in the trail of artists like Valie Export and Peter Weibel, the Fang carry out outlandish actions, such as staging a public declaration of love during a flight or organizing their own wedding on repeated occasions, without the vicars who participate in the successive ceremonies knowing that they have already previously been married.

Kevin Wilson uses the Fang to offer us an entertaining parody on creators, who, above all since the seventies, have insisted on dissolving the barriers between art and life through actions that take place in the “real” world. The American writer offers a portrait of contemporary artists that is not exactly benevolent: the protagonists of the narrative are somewhat pathetic figures, who entertain themselves staging actions that are fairly futile and lacking in substance, the theoretical justification for which is fairly doubtful. The Fang are laughable artists, as is their art. However, what ends up being the most striking thing about these fictitious creators is that they aren´t so different from many real artists, who we are all familiar with. Caleb and Camille, protagonists of a comic fiction, are hugely reminiscent of several characters whose names occupy numerous pages in contemporary art books and magazines.

Nevertheless, the most notable feature of the Fang is their total conviction about the superiority of artistic creation with regard to any other ambit of life. Guided by the certainty that art is the ultimate aim and that it must guide their existence, they allow their artistic pretensions to determine their decisions and actions. They grant art a transcendent dimension and situate it, therefore, beyond any moral consideration. The Fang are capable of doing anything in the name of artistic creation without suffering even minor pangs of conscience. To the extent that they don´t have even slight qualms about using their young children, minors, as part of their performances and are incapable of understanding that they could refuse to participate in their crazy projects..

Ultimately, the Fang appear like a metaphor, a way of understanding the art that has enjoyed huge sway since the beginning of modernity. It is about a vision of creation–that is already detectable in romanticism and has come down to us through successive avant-gardes– according to which art occupies a central place as a motor for human emancipation. From this perspective, artistic production enjoys a special status that enables it to justify all its excesses and arbitrary qualities. To the extent that it occupies a position of superiority over and above any other ambit of life, art doesn´t have to justify itself to anybody, if it is not to itself.

The Fang embody a type of artist who, ordained with his (supposedly) extraordinary nature, is liberated of all moral responsibility: able to act with impunity because in art he finds his alibi and justification. A creator who feels legitimated to commit any excess because he does so in the name of artistic production. Caleb and Camille Fang represent the type of artist that still dreams of totally aestheticizing our reality. The belated inheritor of the totalizing ambitions of movements such as functionalism or De Stijl, that aspired to build a world dominated by the mechanical aesthetic and abstract reason, or like surrealism, that dreamed of imposing a universe dominated by paranoiac deliriums and unconscious pulsations. Like many historic avant-garde exponents, the artist embodied by the Fang possesses a totalitarian vision of artistic knowhow in the understanding that it can determine any aspect of existence.

Caleb and Camille Fang represent a type of creator that is, in itself, anachronistic. Their idea of art as a mission situates them in a time that is not our own. For this, to us their behaviour seems comic and pathetic. Though, in the way the Fang act, one can detect numerous tics that many contemporary creators display today. And, in the end, the novel by Kevin Wilson can be understood as a mockery of a large part of the contemporary art, which finds it hard to understand that its amorality and maximalism are no more than proof that it already belongs to another time.

Eduardo Pérez Soler thinks that art –like Buda– is dead, though its shadow is still projected on the cave. However, this lamentable fact doesn´t impede him from continuing to reflect, discuss and write about the most diverse forms of creation.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)