Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

When stories are powerfully articulated they acquire the form of an event horizon. The space-time divides and what is produced on one side can’t affect an observer situated on the other. In the same way, stories splinter the space and time of history, into the memorable and the forgotten.

The resonance of Lucy Lippard’s discourse reached the exhibition “Open Work in Latin America, New York & Beyond: Conceptualism Reconsidered, 1967-1978” curated by Harper Montgomery at Hunter College. History anchors itself once again in the shelves of conceptual art. For the lovers of conspiracies, conceptualism is a complex, non-linear phenomenon. It can’t be reduced to a chronology but crystallises into networks of power. The story of Lippard persists beyond the evidences reaped by the history of art in the last decade.

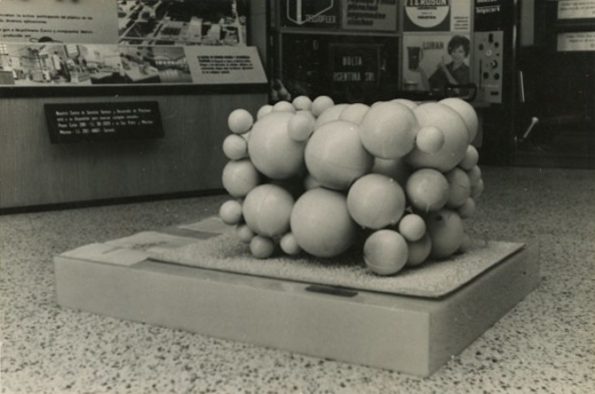

The exhibition “Open Work…” is organised along a theoretical, historical and curatorial vector. Following the theory of Eco, the show is based on a form of poetics where works of art can forge the maximum ambiguity and depend on the active intervention of the spectator, though still remaining “work”.

Secondly, the historical tale is associated with Lucy Lippard, to whom the term “dematerialised art” is attributed. In 1973, Lippard published “Six years: the dematerialization of the art object” in which she revised part of the Anglo-Saxon production of conceptual art and mentioned some Latin-American experiences that can be found in this show (those of the Rosario group and Tucumán Arde in Argentina; the exhibitions realised in the CAyC in Buenos Aires and the works by Luis Camnitzer with the New York Graphic Workshop). Curiously, Lippard didn’t comment on the previous experiences of Alberto Greco, Ricardo Carreira, Oscar Masotta or Roberto Jacoby.

Probably both Masotta and Lippard had read the article “The Future of the Book” by Lissitzky, republished in the New Left Review in 1967. They possibly found there the concept of ‘dematerialization’, interesting as a way of understanding the art of the time. In July that same year Masotta gave a talk in the Instituto Di Tella titled “Después del Pop nosotros desmaterializamos” (After Pop we dematerialize), and in October 1967 published the book “Happenings”, where the early experiences of dematerialised art were presented. Finally a year later he publishes “Conciencia y estructura” (Conscience and structure) where he refers once again to some of these projects. What is curious about these connections and coincidences is that Lippard made no mention of the existence of Masotta and the media art group. Not just because she met artists from the city of Rosario who had worked with one of the members of the mass media art group in Tucumán Arde or because she visited El Di Tella, but because she knew a direct disciple of Masotta.

Thirdly, the exhibition forms part of the collection of Patricia Phels Cisneros and the work of the curators Gabriel Pérez Barreiro, Sofía Hernández Chong-Cuy and Skye Monson. This collection is conspicuous in its lack of important pieces of dematerialized art that have been discussed in numerous investigations and exhibitions over the last decade: ” Global Conceptualism” at the Queens Museum, and “Heterotopías” at the Museo de la Reina Sofía in Madrid, “Conceptual Art: an anthology” by Alberro and Stimson, “Conceptual Art” by Osborne, “Rewriting Conceptual Art” by Newman and Bird, and the works of Longoni and Mestman, Giunta and Katzenstein.

One demonstration of the standing of an institutional collection like that of Cisneros, ought to be carefully examining the investigations into conceptualism that are being developed in diverse parts of the world, and not remaining petrified in the face of the advances made in the investigation of art and curatorial practices. An institutional collection is not built up out of commercial interests nor personal caprices, but through historical investigation.

Syd likes doing lots of things. His maxim for life is not unlike the famous paragraph in The German Ideology by Marx and Engels. He gets up early in the morning; does a bit of exercise, plays the guitar, draws, writes and films. He works in a liminal zone between art, sexuality and politics. Syd navigates happily between the intellectual field and the world of art. He’s a doctor but not the type that cures anything.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)