Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

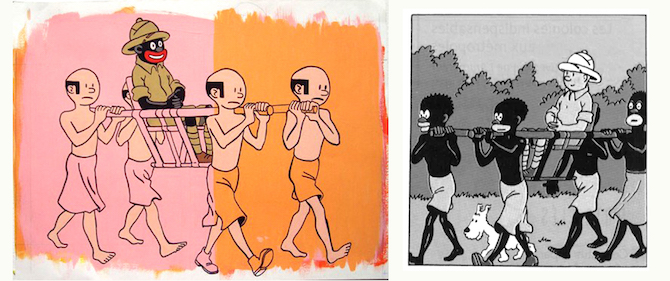

I still remember the image of a small, tattered, black and white photograph in which a young Pablo Picasso appeared, sitting with his shoulders curved, a bit like a child, in front of a small chaos of various African sculptures, in his scruffy Bateau-Lavoir studio in Montmatre. Africa constituted a veritable inspirational reference for “exotic-primitivism” for the avant-garde, who believed they could discover in it one of the last bastions to shelter from the advances of history and modernity. A cherished nook in which to rediscover the “true” primeval id, natural and wild. Today, more than a century later, Africa continues to be envisioned in in our imagination as a tribal world, running parallel to a contemporaneity anchored in a continuing development to which, however, there is already little left to bring. A vast, complex cultural construction, with roots that extend from Hegel and R. Kipling, through to the charming Tintin. “While the lions don’t have their own historians, hunting tales will always glorify the hunters” (Chinua Achebe, Nigerian writer, in an interview with the The Paris Review 1994). Okwui Enwezor, consultant curator for the show Making Africa. A continent of contemporary design jokes: “Since I can remember I’ve read in the media how families in Africa survive on a dollar a day, but after so long, have they not had a rise in their earnings? Would they not now have reached at least a dollar and a half?” So perhaps the best way of beginning the exhibition would be through the extravagant glasses of Cirus Kabiru. Lenses without any shining glass embossed with cast-off materials that do, however, fulfil their function, of converting the spectator into an eccentric insect; one that in the form of a Kafkian metamorphosis, can look at Africa from a new perspective.

The first step proposed in the Prologue of the exhibition is none other than to question who, historically, has spoken for Africa and how they have done so. Antoni Castel, a founding member of the Centre d’Estudis Africans in Barcelona and co-director of the postgraduate diploma in Conflicts and Peace Communication at the UAB accompanied me through the corridors of the exhibition. He already established in his doctoral thesis, compiled in the book Malas noticias de África (Bad news from Africa), the stereotypes and simplifications in which the Spanish press incurred between 1992 and 1998 when communicating on the three big African wars (those of Somalia, Ruanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo) as well as the asymmetrical division of power between chroniclers and protagonists. But the rules of the games are changing. More than 20 years later, both have the opportunity to see works such as My Africa is or Slum TV in which it is the Africans themselves who denounce the distorted representation of Africa and claim the right to self-narration. The new digital context has returned the voice to the lions, the young, urban middle-class African has picked up the reins without a by your leave, taking advantage of the current opportunities of the internet to share with the rest of the world their own testimonies recounted in the first person, to stop being mere consumers of global culture to become producers.

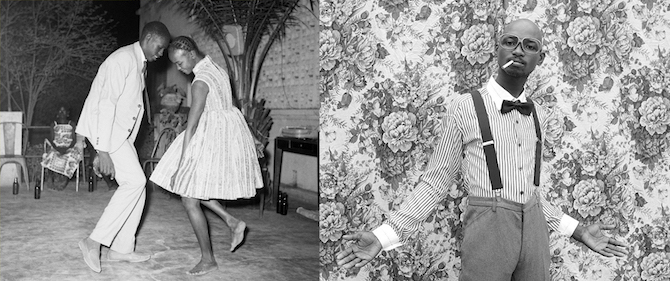

Despite the bad omens of digital fracture, Africa has managed to hook up and, just like the first post-colonial generation portrayed by Malick Sidibé, celebrate their new position with optimism: “Now it’s our turn!” Just as Amelie Klein, curator of the exhibition, confirms, “Africa is normally associated with drama but currently an entire movement of celebration is being gestated and the celebration is constituted, without any doubt, as political power.” Castel reiterates this perception: “one of the things I like most about Making Africa is that it’s not your average exhibition, that revises once again the pre-colonial African artistic heritage or backslides into its more tragic side, so much as, in spite of everything, makes evident this burst of life, at a time when notwithstanding Europe seems tired. One can feel the “pride to be African”. The person who lives in Dakar has practically nothing in common with someone who lives in Addis Ababa but they share the honour of pertaining to a common entity, one that on one hand has been treated very badly. It is interesting that the exhibition brings together pieces of contemporary art, design and architecture similar to those we could find in Berlin, Great Britain or USA, demonstrating that the interlocutors find themselves on the same level of dialogue”. As Okwui Enwezor establishes: “Simply by situating themselves on the same level gives rise to a real collaboration, and collaboration means to explore differences as mechanisms for reinvention. Mechanisms that go beyond oneself, beyond one’s own pillars, or certainties”[[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=khNz6rWTSOU]].

The works of the over 120 creators and authors participating in Making Africa, illustrate the different gaze that Africa directs upon the world, which inverts the logic of the traditional Western dynamics. Such as, MPSA, a service for transferring money by mobile phone, that has allowed many people with meagre incomes to operate on the margins of the traditional banking system that they can’t access. Today this service, born in Kenya, has already over 12,2 millions of users (“Paying for a taxi ride using your mobile phone is easier in Nairobi than it is in New York” announced The Economist in 2013) and it has been exported to Europe and Asia. “One of the motors of growth in Africa is its “informal economy”, not controlled by official bodies but that nevertheless represents 70% of the total economy. We ought to be capable of seeing the potential that this informality has, this capacity for self-organisation. I’m not saying that it is the solution for everything. It’s obviously plagued with precariousness. But it also brims with creativity.” (Amelie Klein)[[Amelie Klein, Exhibition Tour “Making Africa -A Continent of Contemporary Design”:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7zXw-CwUDqs]].

On the other hand, projects such as Taboo by Bibi Seck or the tyres of Amadou Fatoumata Ba, defy the trends for mass consumption through recycling. “One of the things that most destroys African economies is the importation of cheap goods. Faced with this, many Africans vindicate the political use of Making (the renegade practice of Making) as a form of research, arriving at new tropes, new industries and new concepts” Okwui Enwezor [[Opening Talk: “Making Africa -A Continent of Contemporary Design”:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y-_n1R0WH4E]]. Fablab in Wólof means “do it with others” and it is used to denominate a new series of work spaces, open to the World Wide Web, that propose open code manufacturing technologies, offering to the young the possibility to find for themselves solutions to the problems of their communities. Hence the importance of “Making” Africa.

Beyond its undeniably bitter side, the time has undoubtedly come for a change of perspective that also talks of Africa as a protagonist of the present, without masks, that doesn’t look to the East, or to the West, so much as forwards. In any case, initiatives like Making Africa arising in the heart of white Europe, the Vitra Museum (situated at the frontier of Germany between Switzerland and France) also prove that fortunately it’s not just the lions that are capable of being critical of their hunters.

Those who know Amaia well, call her affectionately “la contreras”. For she spends hours, as if she has time to spare, debating, thinking and rethinking, analysing, deducing, responding…There are even those how have caught her in fraganti disagreeing with her pencil, in the margins of the pages, with the author of this book that by chance has landed in her hands. It was just a question of time before she ended up writing her own reflections in the hope that at some point somebody would read her ruminations, pencil in hand.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)