Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Growing up in Lebanon in the 90s, I would often come across the words shādh.a or monḥarif.a while reading the Arabic subtitles of foreign-language films or television series. As a very young linguaphile, I had a habit of pulling the heavy dictionary off the shelf and flipping through it in search of the meanings of words I encountered. Surprisingly, both adjectives referred to someone deviant, irregular, odd, eccentric, etc. As I got older, I made the connection that these words were specifically used as an Arabic translation for “gay” or “lesbian.” This phenomenon did not stop at the edge of the screen but seeped into everyday conversations across the Arabic-speaking world: gay people are deviants.

Understandably, the LGBTIQ+ community was troubled by this terminology, and following years of awareness campaigns and lobbying efforts, shādh.a and monḥarif.a slowly disappeared from the subtitles sitting at the bottom of our screens, gradually replaced by the politically correct term mithlī (same-oriented). As a young gay man, I was outraged as well; I did not want to be called a deviant. I remember correcting my parents on multiple occasions, insisting on the “correct” term for someone who is gay, long before I even came out to them.

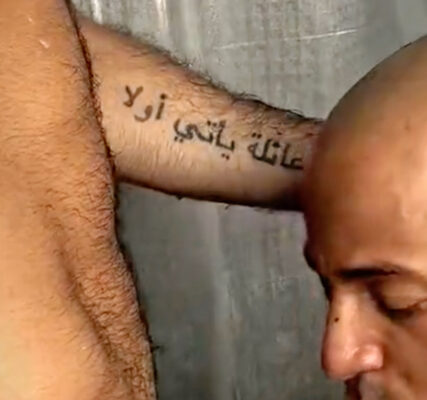

In 2024, I published a compendium of queer Arabic slang titled The Queer Arab Glossary (Saqi Books). The book surveyed the words and expressions used across the Arabic-speaking world to refer to someone who is, or is perceived as, queer —whether affectionate or derogatory. By the time my book came out, the genocide in Gaza was underway, identity politics lay on its deathbed, and capitalism had absorbed all the radical energy from queer discourse. In that moment, as I travelled across the world over three months engaging audiences with my book, I found my own position shifting. I could no longer relate to the terms we had fought so hard to adopt but gravitated toward “gay,” or even “faggot.” I no longer wanted to be part of the queer mainstream, as it seemed like yet another tentacle of a sick world I had chosen to abandon. I don’t want the norm, nor do I want to assimilate. I want to stand out —like a thorn in your side— I want to be a deviant.

We owe an immense debt of gratitude to the deviance of queer discourse. Not the kind that changes its social media avatar to include a rainbow flag, but the kind that shakes society to its core and forces it to confront its own prejudice and hypocrisy.

We are living through a dark and pivotal chapter in history, particularly in the region I call home. As Zionist forces, with the full backing of the US and EU, unleash barbaric violence onto my people and their land, I chose to present texts by four queer voices from this very land, in an attempt to resituate queer discourse back into its rightful radical stance.

In Takweer: Archive as World-Making, Dr. Sophie Chamas explores Takweer’s queer Arab archival practice as a means of challenging the tearing apart of queerness from Arabness. Meanwhile, Yasmine Rifai and Nadim Choufi reflect on their recently published anthology of queer Arab art titled I Will Always Be Looking For You (also the title of their article). Their powerful book does not claim to know what our Arab queerness looks like, but instead searches and searches and searches, through twenty-two contributions about thirty-one artists.

In Faggety Fag Dreams Between Thieves Street and Lazarus Gate, writer and translator Rana Issa imagines a queer utopia hellbent on destroying fascism while simultaneously reveling in its boundless deviance. Finally, I conclude the month with a text titled Try not to choke when you speak my mother tongue. Try it, yalla. Although it does not explicitly contemplate queerness, it unpacks the ways the West has weaponized text and imagery to construct an idea of “the Arab” in the psyche of its masses —and how that idea shifts and adapts to perform various propagandistic roles, one of which is the gay-hating Arab, a lie that even some Arabs have swallowed.

It is in our very deviance that queer liberation is sustained. It is in the deviance of the oppressed —whoever they may be— that collective liberation is sustained. Moral panic is nothing but a red herring. In moments when horror is tangible, we should leave no room for ambiguity. Let us be explicit and let them clutch their pearls.

Marwan Kaabour is a graphic designer, artist and writer. His interdisciplinary practice builds pathways between communication and publication design, curation, pedagogy and political activism. He also works with non-profit institutions, companies and individuals in arts and culture. In 2019 founded Takweer, an online platform and expanding archive of queer narratives in Arab history and popular culture. His debut book, The Queer Arab Glossary, was published in June 2024.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)