Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Francesc Ruiz – When I invited you to participate in this issue of a-desk, you told me that you were creating a new body of work in which, by means of a large diagram, you were making visible the development and links between the French Enlightenment and the Haitian Revolution. Could you briefly describe what this new production consists of?

Efrén Álvarez – Well, this will be the first time I talk about it and I’m afraid I might stumble a bit, but here goes…

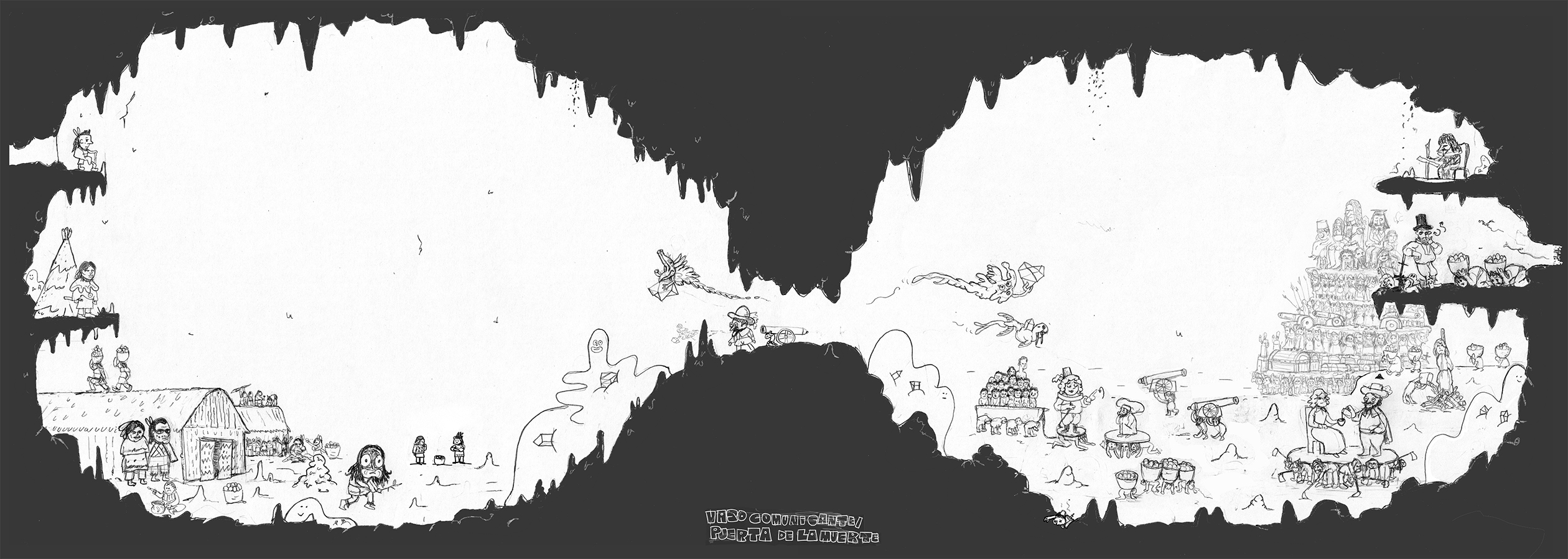

I try to represent the social body of the 18th-century revolutionary period by focusing on the French colonial empire and the brutal economy of the era, although the main focus will be the process of ideological formation, that is, the global republic of letters, conspiracies, agencies, and machinations. What form will it take? Analogies, similes, parodies, metaphors, similar to what I did in my work Government, and it will end up forming a kind of recognizable collective being. It’s not going to be a map of the events, instead I hope to represent the institutions that produced that moment which was so horrible for so many people and so historically significant.

Haiti and Paris will be the main figures of the image, parallel revolutions that can present the problems that I want to deal with in these drawings, revealing the tensions between explicit ideologies and more visceral currents.

One moment at the center of the time frame was the parliamentary sessions of the French National Assembly dealing with the abolition of slavery, which C.L.R. James wonderfully documents in The Black Jacobins. After the promulgation of the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in 1789, anti-slavery was very present socially, with best-selling novels, pamphlets and plays denouncing it. Parliamentarians from the bourgeois left in power at that time, such as Brissot, Abbé Grégoire and Condorcet, formed the anti-slavery society that made a parliamentary initiative to abolish slavery.

Even so, together in an assembly, having the authority and supposedly the consensus to change the situation, they all let slip the goal and concluded that there was no rush to establish equality. The idea of breaking the chains of slavery ended up merely a metaphor, until the Haitians managed later to turn it into a reality by force.

Drawing and thinking about these failures of ideology, in the face of who knows what other forces, is a recent goal that I hope to address in this project.

FR – When we first started talking, you recommended me Robert Darnton’s book The Devil in the Holy Water, or the Art of Slander from Louis XIV to Napoleon, which focuses on the study of libel as a means to create a state of general opinion that led to the social upheavals of the French Revolution. As I read the book, I remembered the zines you’ve been publishing over the years, both those where you describe your research into power structures, the market and politics and the satirical zines that focused on Who’s Who? in the contemporary art world in Spain, which you published together with Víctor Jaenada and which temporarily revolutionized the scene. Between libel and the anarchist fanzine, where do you place your fanzine practice, your photocopied drawings and your website goodgore.com?

EÁ – Libel had great power compared to what can be done even in the mainstream media today, since there was only one royal authorized newspaper and official censorship of all publications. Those interventions were huge. I’m more interested in the underlying reality that they conveyed than who they slandered. At an atavistic level, associating royalty with vulgarity, with common people, was the most injurious insult possible because it eroded the distinction aristocracy intended to produce. The underlying equality was not slander, it was just reality, a legitimate struggle to be built.

In the art world we are separated in a social scene in which we produce things that usually don’t have an immediately verifiable impact. Libel at times was a direct form of extortion. The author could demand through intermediaries a kill-fee before they released it to the authorities, or a censor, a police officer, could be contacted to ensure the reputation of the monarchical institution.

If I think about it, I published, with Víctor Jaenada, a secret story, which was a kind of libel. Many libels of that time were secret stories, scandalous stories, true stories. In our case, it dealt with the events that occurred in 2016 during the censorship scandal at MACBA in the exhibition La Bestia y el Soberano (The Beast and the Sovereign), in which we told the true story of a scandal.

Other commonalities between my fanzines and libel is the ancient comedy of Aristophanes which is characterized by the use of explicit allusions to and often unfounded criticism of people who are likely to read the text.

My other fanzines may have a Platonic libel intent, but I think they are a bit more conventionally artistic in style. I started by imitating Mike Kelley’s supplementary materials and Ion Grigorescu’s DIY catalogs. Anarchism is the base, though without formal influence.

FR – Interested as I am in the global distribution of pornographic comics, it’s interesting that many of the leading philosophers of the French Enlightenment published porn, something that isn’t surprising at all if you look at the large publishing groups in Spain that promoted porn during the transition. Your work is often full of sexual and scatological iconography organized in flows of anal penetrability. Parody porn is a very powerful way of transmitting ideas. Where does this imagery come from and what are your influences?

EÁ – “…organized in flows of anal penetrability.” Wow! Thanks for the description, I’ll use it in future projects.

In my case, I find drawings with sexual iconography very interesting and I am incorporating them more and more. I could say that I also started imitating contemporary art. At first it was a technique to give artistic grandeur and expressiveness to my drawings, but now I do it more conscious. I believe that it’s important to participate in the sexual revolution of the present.

FR – If libel was the fake news of the time from the Grub Street printers in London that generated the breeding ground of the French Revolution, the distribution of revolutionary ideas in Haiti was generated through rumor and orality. In The Common Wind: Afro-American Currents in the Era of the Haitian Revolution, Julius S. Scott shows us how information coming from France circulated quickly through the networks configured by all those bodies that were resisting being governed…

EÁ – Since you mention the circulation of ideas across the Atlantic, another of the problematics I am dealing with is the possibility of indigenous participation in the production of the ideologies of modernity.

David Graeber, rest his soul, has a book coming out this January on the theme of Scott’s Common Wind, called Pirate Enlightenment, and it explores the possibility that revolutionary ideas not only circulated but were also generated in the colonial world. I also deal with this subject, which was discussed by Wengrow in The Dawn of Everything, in this project.

The example of the communities of the colonial world has an enormous presence in modern thought and can be called a literary genre of dialogues with otherness, but until recently, this was seen as a passive contribution by said communities. Now, with the contribution of Graeber that documents the work of historians and anthropologists who collect and study the indigenous voices in historical archives, we can imagine how in the centuries of colonial interactions there were active dialogues that have been ignored. It’s a bit like seeing the Enlightenment as the typical scene in which a grumpy sergeant gets an idea that the poor soldiers have been repeating to him all day.

To give an example, from 1736 to 1760 Benjamin Franklin was printing and commercializing treaties and diplomatic, political speeches of Native Americans with great success. According to old ways of seeing, these were mere curiosities, but if we consider their intellectual influence, they are not insignificant, especially when coming from Benjamin Franklin, the influencer.

FR – The bodies of resistance in the holds of slave ships, in plantations, in runaway slave towns and in the incipient cities of the Caribbean organized themselves, and those undercommons, in the words of Harney/Moten, are still active today. Where do you currently find these resistance networks in a context like Barcelona?

EÁ – I don’t really know what to tell you. I’ve tried to get closer to various political groups but without much success. Ideally, I would like to develop my cultural life within the context of politicized groups, as in the 1930s, but I am not sure it’s possible, although I haven’t given up yet.

I applaud the most autonomous forms of resistance, which are the undercommons as you say, whenever I can, but due to my work and the virus I am not very involved, and from the outside I prefer not to judge.

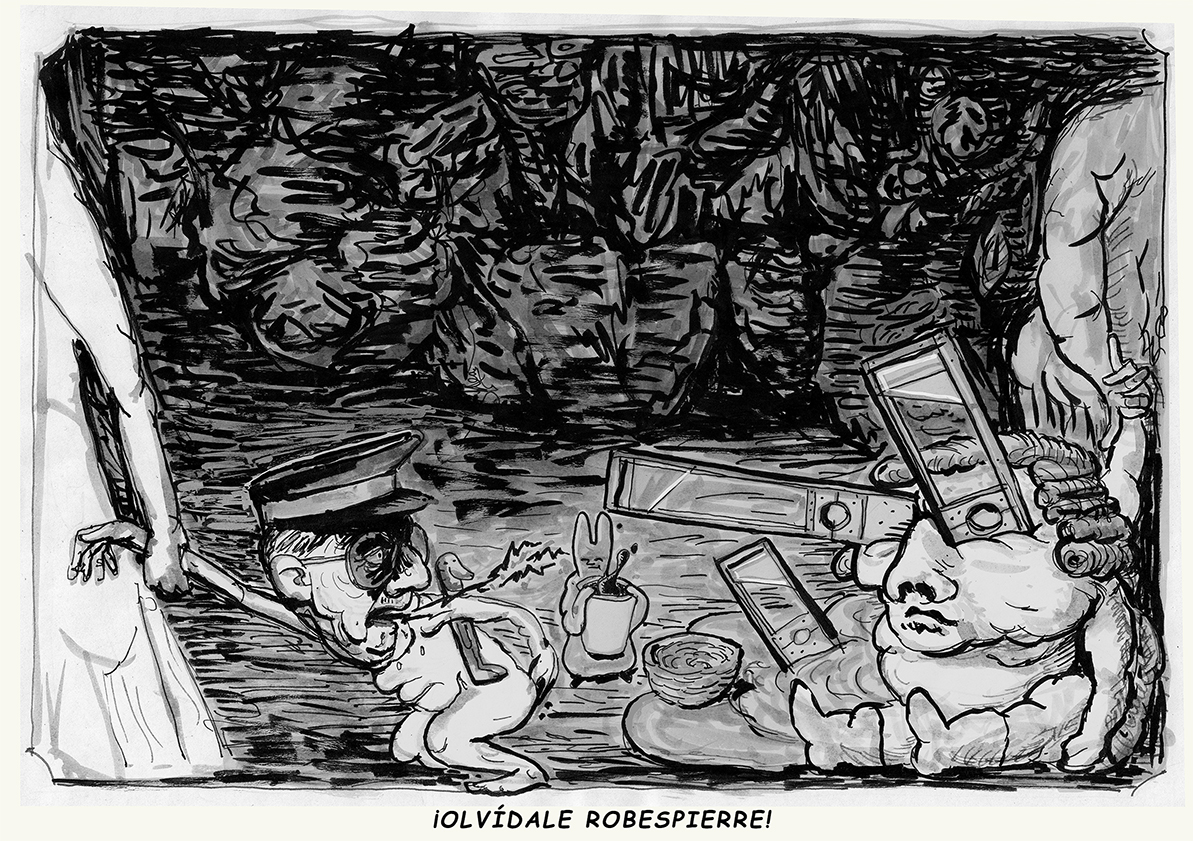

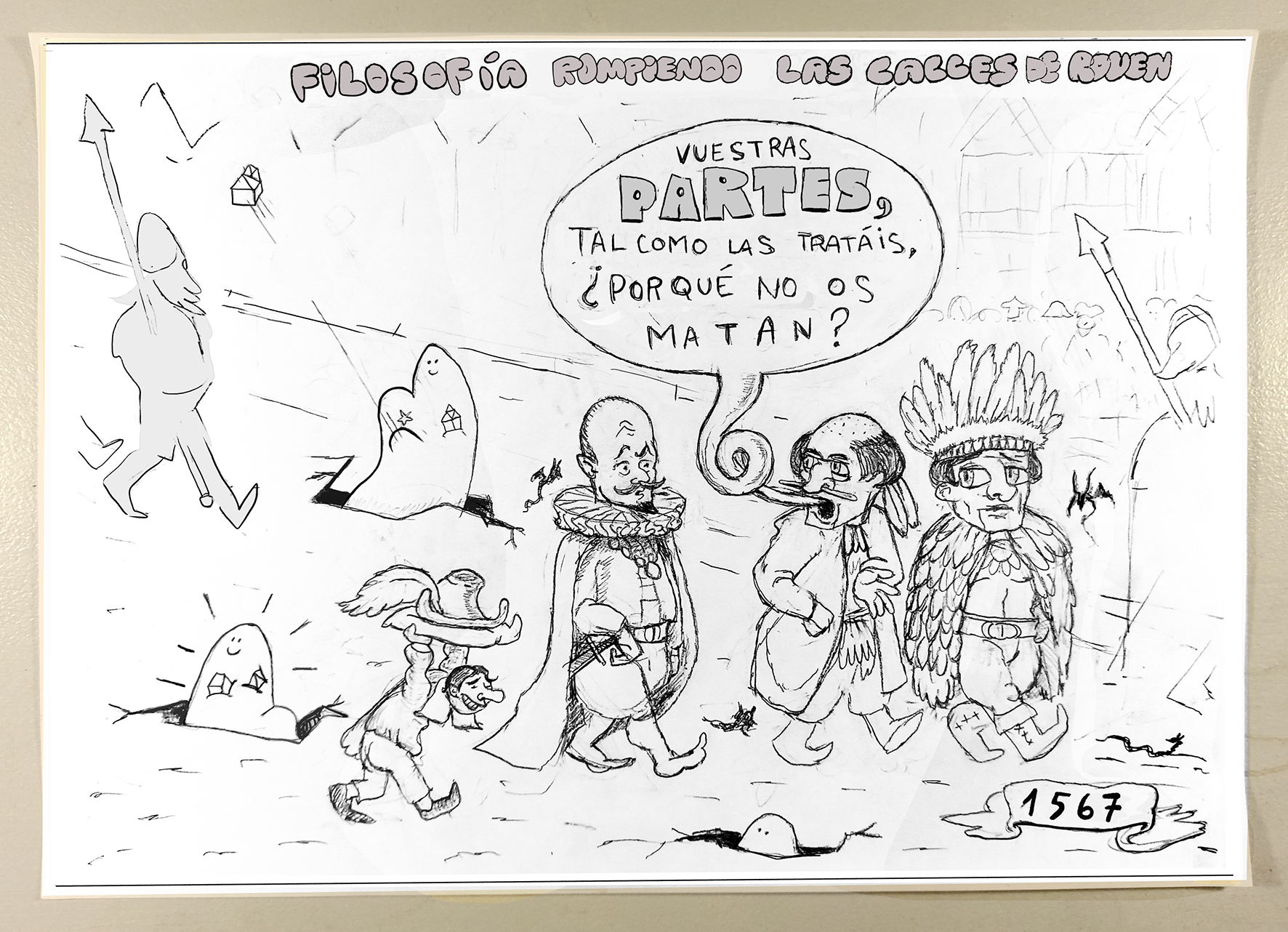

[Pictures inspired by Museo del Prado lectures, 2022]

Francesc Ruiz (Barcelona 1971) departs of the comic as an aesthetic, narrative and intellectual substrate and also as historical and operational material, applied as a container or description of reality. Through creation, alteration, restitution or coupling, among other ways; it generates possible stories that reveal the gears through which individual and social identities, sexual identity or even the identity of the city are built.

His installations have been seen in different national and international art centers and museums: EACC (Castellón), CA2M (Madrid), IVAM (València), MACBA (Barcelona), Gasworks (London), FRAC PACA (Marseille), Weserburg Museum (Bremen) and in biennials such as Venice in 2015, Götteborg in 2017, the Momentum biennial, Moss, Norway in 2019 or the Busan biennial in 2020.the text

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)