Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

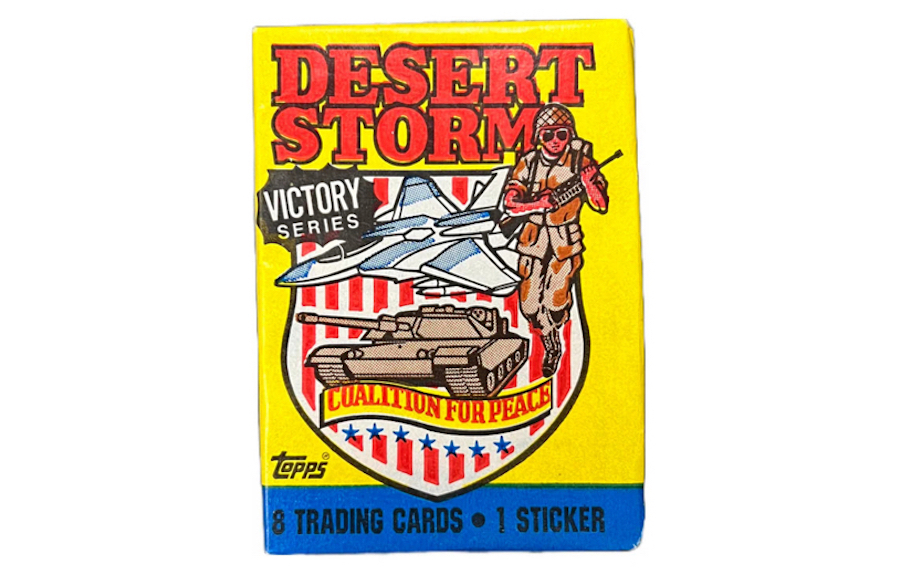

Not too far from the hustle bustle, there is a store in the Lower East Side of New York that specializes in old trading cards. Walking into it and rummaging waxed and foiled packs of Gremlins, Power Rangers and the Chicago Bulls that are all still accompanied with intact chewing gum from decades past, there is one other deck stacked in the corner that sticks out from the overall cheerful tone. With a shimmering blue cover highlighting wicked drawings of a fighter jet and a locked and loaded soldier, it must have taken its title Coalition for Peace to purple heart.

When it began circulating in 1991, these trading cards were the somewhat official Desert Storm collectables that tried to make the First Gulf War cool. Kids and teenagers from the self declared greatest country on earth exchanged cards showcasing The Power of the Tomahawk in obliterating Iraqi and Kuwaiti buildings, as well as an entire deck of firearms, guns, tanks and warships. War machines aside, a few of the faces on the cards became collectibles too. Lucky traders might have stumbled upon cards of a mischievous looking Saddam Hussein, while others got a hold of the composed Commander in Chief, none other than George H.W Bush himself. But it was the cards of camouflaged, determined soldiers who were Ready For Action and were The Backbone of that entire operation that threw an interesting linguistic light into the collectibles: in the American imagination, the Gulf War is still regarded as the most mature and sensible invasion to have taken place in the country’s recent memory. What was unprecedented about it were the medical-like words its government officials and mass media have used to describe it: Surgical strikes. Accurate precision bombs. Precise and devastating air attacks.[1]These examples have been taken from The Future of Air Power in the Aftermath of the Gulf War, 1992. Unlike the blunders of past wars, the Gulf War has taken healing terminologies so as to disguise its inflicted wounds that killed thousands and displaced scores more. For the sake of reinforcing the language of technological advantage, other images from the war were distributed. Not from the humane perspective of a journalist on the ground, but rather that of a lens mounted on a bomb from up above. Descending on its victims, Smart Bomb Vision was mounted on missiles so as to better their aim. Or so the official statement went. In reality, General Norman Schwarzkopf who commanded the invasion congregated the press so as to show off the footage garnered from such devices. General Charles Horner who attended the briefing admitted that people “can almost get airsick watching this”.[2] Smart Bomb Vision by Roger Stahl © 2019 Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick.

AGM-65E Scene Magnification Maverick here attached to an RNZAF A-4K Skyhawk © 1993 – 2010 Carlo Kopp; M645/1000S

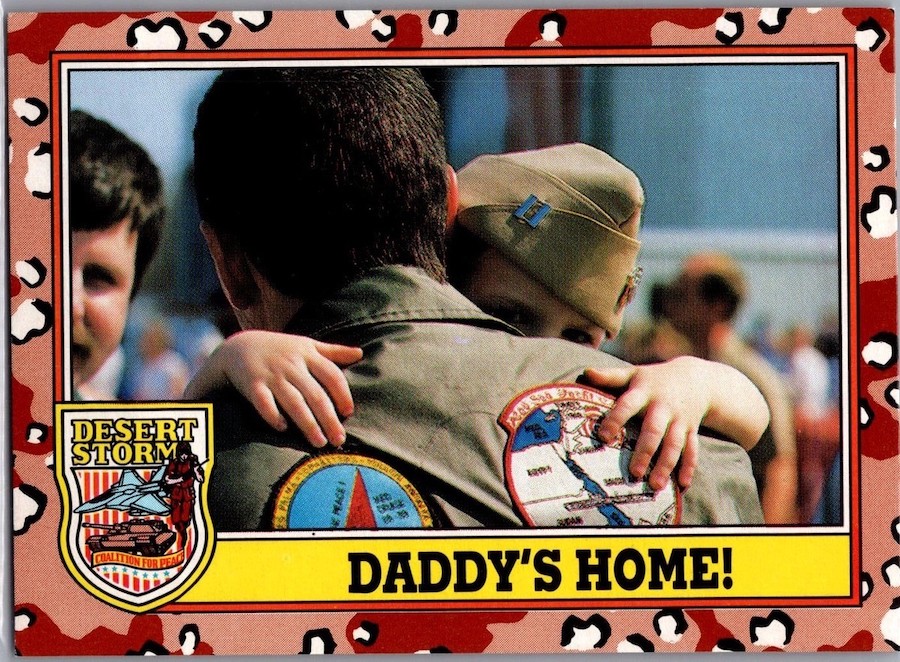

Looking back at the Desert Storm Trading Cards which included General Schwarzkopf, it is also clear how making a war appear cinematic meant sterilizing it from the torn limbs and obliterated homes involved in its making. Those cards were an obfuscation of violence that hid their actual consequences. Becoming the warning of philosopher Jean Baudrillard that “the image consumes the event, in the sense that it absorbs it and offers it for consumption”. War bonds of such kind have been established as a bizarre path for offsetting the cost of war onto the individual consumer. Moronic and kitsch as the Coalition for Peace cards presented themselves to be, their existence is not unique. Trading cards, action figures, televised specials and other such patriotic merchandise are made into a personal choice to excite oneself, moralise and economically support the armed forces based on basic notions of nostalgia and collectible rarities. Fictionalising reality, gaming and entertainment industries that commercialise actual warzones excite its consumers to support and gamify brutal acts. Unlike a collective or governmental dictation to do so, consumption means granting oneself the illusion of doing one’s part in the course of war.

Branding all that is gruesome about battle grounds as thrilling or uplifting seems to possess all militarized cultures. Wartime creates pastime. Whenever troops step their feet across foreign territories, cultural industries are indistinguishable from their warfaring counterparts. Patriots can count on popular culture to be there and foment the notion that participation in warfare is perhaps the most efficient path for achieving personal growth. Patriots could count on morning shows to set up a sobbing reunion of a uniformed father with his war stationed son, and for reality television shows to salute pious-like commanders of wars who, despite not being able to afford a home, gave their all to their homeland. Patriots can also count on online masterclasses offered by war criminals and commando leaders to remind flag waving viewers how to build “battle-ready” work environments– soft skills are carried with hard guns.

Cards were not the sole thing that was traded. Over a decade later, the United States had sustained material attacks on American soil during 9/11. But, as Retort Collective suggested, such attacks were also symbolic and visual assaults on the global image of American dominance. Retort then argued that the War on Terror and its invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq were partially a genocidal pursuit for generating spectacular images that would heal that wound.

Retribution of such kind is also the device that frames the ongoing regional war in the Middle East and the carnage Israel is conducting on the Palestinian people. Much like 9/11, October 7th might be understood as a similar image wound. Locally, hundreds of innocents were killed on that day. But globally, the public image of Israel as an indestructible nation state was punctured. The pain of that wound was then harnessed in order to justify the subsequent Gazan Genocide. Yet unlike armed conflicts of the past, current images of war are not as well curated. With no means to produce cinematic depictions of warfare, actual documentation from the largest active mass grave in the Levant unveils its true essence. Israeli soldiers upload to social media their stand-up performances in decimated and evacuated Palestinian neighborhoods. Singing songs and cracking jokes; sleeping in abandoned cribs; dancing in obliterated schools.

An Israeli boy wearing a military vest throws a mock grenade during a traditional military weapon display to mark the 66th anniversary of Israel’s “independence” at the occupied West Bank settlement of Efrat on 6 May 2014. Gali Tibbongali/AFP

Brute force becomes a fixed component for creative expression as well as most consumption habits: popular culture and the market in militarised conditions become inseparable from the war that supports both. But the proliferation of the military in every nook and crevice of a given society means that without war, large chunks of its culture will cease to exist. Take as an example how Israeli weddings are being officiated in military bases. How births are taking place with parents wearing state-issued khaki uniforms. How, in a farcical historical repeat echoing General Schwarzkopf, national streaming services broadcast their own smart bomb vision on Gazan homes. How classrooms, commercials and public spaces in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem are suffocated with blue and white flags and desperate combative mantras. For some to feel most alive, others must die. What all this means on a more psychological level is that armed service within a militarized culture becomes a funnel for all human experience, emotions and expressions. Being a soldier means more than just participating in a bureaucratic meat grinder. Because warfare makes itself an integral part of sense making, it shapes itself to be a moral barometer. But to be clear, militarization does not entail full conscription or a robust fighting know-how. Were that to be the case, Switzerland would be menacing. What militarisation does entail is a suffocation of all other emotions, social habits and cultural cues,absorbing them into the armed apparatus itself.

Israeli commercial for a pregnancy ward. The caption reads: “Recipient of the President’s Award of Excellence for the year 2038”

Because the army sets the parameters that determine internal values and social morals in militarized societies, it also invades the fantasies, ambitions and dreams of all its supporters as well as its victims. Becoming part of our decision-making processes, champions of war infiltrate emotional reasoning too. It develops abilities and shapes realities. Time itself becomes measured as the duration of time set between wars. Just as the forties are no different than the Second World War for most Europeans and the sixties were a stretch of time spent in Vietnam for Americans. Israel, however, for its most part exists within the matrix of perpetual warfare. Warfare builds a robust and confident inner world in exchange for taking part in the destruction of the physical one.

Compulsive needs to protect the nation state in territorial, visual and linguistic terms has become more egregious over time. Rightful opposers to the slaughter of children are often asked if they support the right of Israel to exist. Yet it is worth noting just how perverse such a question is. Even according to the most conservative philosophies, it is not private individuals that need to ensure the existence of states; it is the role of states to ensure the existence of the people who live within them and not at the expense of those who do not. The fact that people are now asked to protect institutions, rather than vice versa, shows just how such institutions are as brittle as houses of cards. Humanizing a nation will forever lead to a complete alienation of human lives.

| ↑1 | These examples have been taken from The Future of Air Power in the Aftermath of the Gulf War, 1992. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Smart Bomb Vision by Roger Stahl © 2019 Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick. |

Adam Broomberg (b. 1970, Johannesburg) is an artist, activist and educator. He currently lives and works in Berlin. He is professor of Photography at Istituto Superiore per le Industrie Artistiche (ISIA) di Urbino and Practice supervisor on the MA in Photography & Society at The Royal Academy of Art (KABK), The Hague. His most recent work “Anchor in the Landscape” a large-format photographic survey of olive trees in Occupied Palestine was published by MACK books and exhibited at the 60th edition of La Biennale di Venezia.

Ido Nahari is a writer and researcher currently pursuing his doctorate in sociology. Previously an editor for the street newspaper Arts of the Working Class, his writing has appeared in numerous journals and magazines. He has lectured in various museums and academic institutions across the United States and Europe.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)