Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

There are places where art isn’t merely displayed—it is almost invoked. Perched atop a hill in Coimbra, the Monastery of Santa Clara-a-Nova stands still. Its Baroque architecture, with high vaults and stone corridors, holds centuries of female history, spirituality, and seclusion. In this memory-laden space, Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller have recently presented The Factory of Shadows, a monographic exhibition conceived within the framework of Anozero Coimbra, during the years between biennials.

The Monastery is one of those rare spaces where time seems suspended, and the sounds of the stones can, quite literally in this case, be heard. Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller don’t simply occupy the historic building—they reactivate it. They make it speak, breathe and tremble through a dozen immersive multimedia installations that blend voice, music, objects, and architecture. The works indeed awaken an acoustic sensitivity, turning the building into a constellation of listening surfaces, a sonic chamber, a resonant body.

The Instrument of Troubled Dreams, 2018

Sound Sculpture

For Cardiff and Bures Miller, sound is not just a medium, but rather a matter that sculpts the space. Their practice defines what is known as sound sculpture: a way of composing with and through architecture. In À l’écoute[1]Jean-Luc Nancy, À l’écoute, Paris: Galilée, 2002. Translated into English as Listening, trans. Charlotte Mandell, New York: Fordham University Press, 2007., Jean-Luc Nancy writes that “to listen is to be in the world,” not as a subject in control, but as a body crossed by resonance.

Much like The Forty Part Motet (2001), which resonates through the space, turning the room into a choral body. The forty speakers that reinterpret the Renaissance motet Spem in Alium by British composer Thomas Tallis create a polyphonic architecture that resonates with the listener. Whilst in the kinetic sculptures Imbalance (1994–1998), that spatiality becomes unstable, as if sound were overflowing its coordinates causing them to oscillate. The vaults of the monastery amplify this experience. The echo is not a remnant, but an invisible presence that inhabits the space. Listening here becomes also a form of openness to what once was, to what still vibrates, and to what is yet to come.

Imbalance.6 (Jump), 1998, George Bures Miller

The Factory of Shadows: Spectral Time and Hauntology

In many of their works, Cardiff and Bures Miller engage obsolete technologies, disembodied voices, and anachronistic machines —vestiges of the past that persist like specters. Mark Fisher referred to this sensation as “hauntology”[2]Mark Fisher, Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures, Zero Books, 2014. Available on line here.: a present haunted by a past that refuses to disappear and a future perpetually postponed.

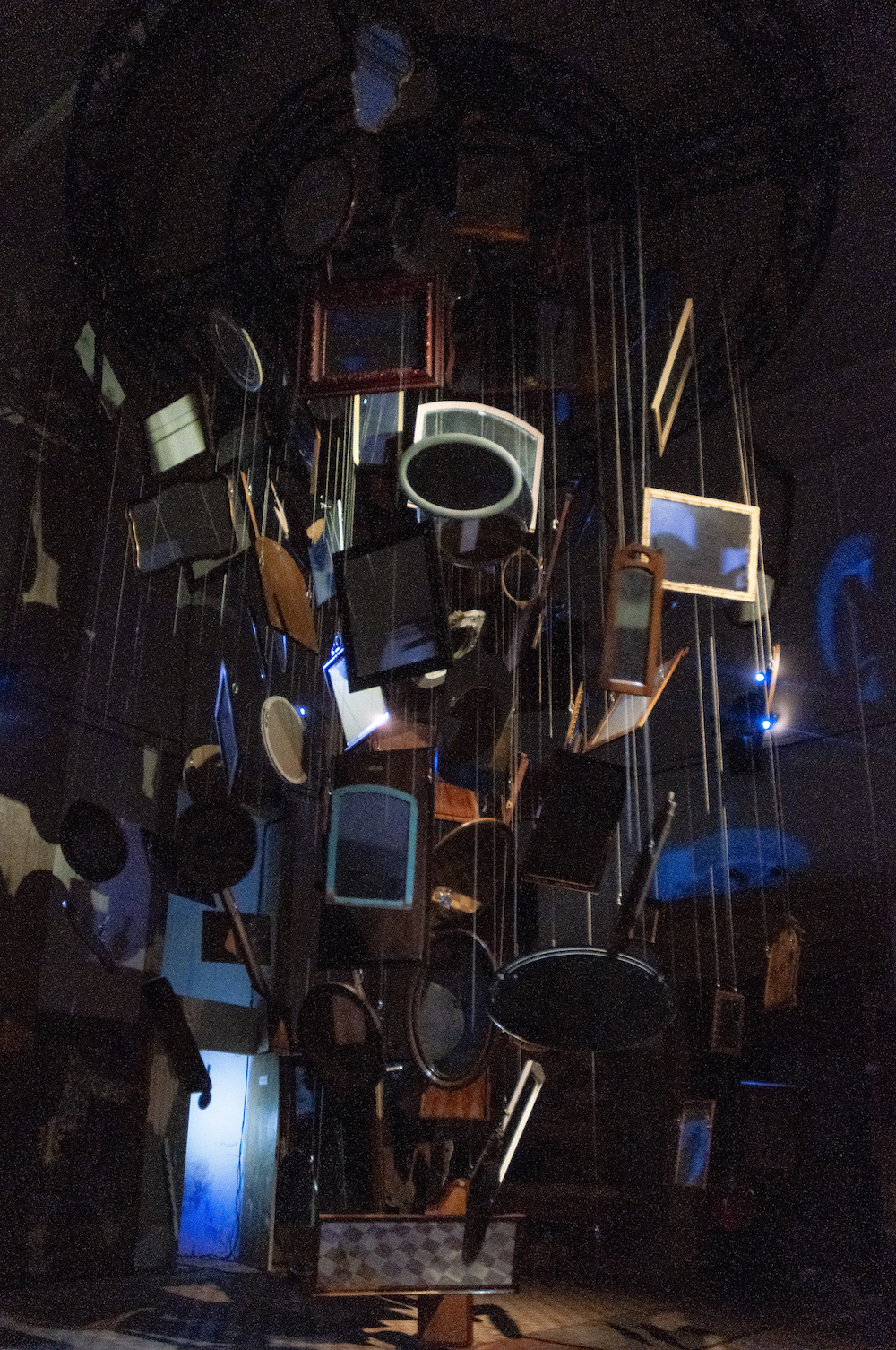

In the artwork The Infinity Machine (2015), cosmic reverberations from NASA recordings swirl in a vortex of antique mirrors suspended from the ceiling, swinging like a pendulum between the cosmic and the residual. Between Houston and the cloister, as if time were folding in on itself. To Touch (1993) is a tactile sound piece in which, by touching an old table, sounds and voices are activated, creating an intimate and spectral experience. On the other hand, the interactive installation Instrument of Troubled Dreams (2018) transforms a vintage mechanical Mellotron synthesiser into a sensory artifact that unfolds overlapping layers of sounds —water, sirens, weapons, music, voices —allowing participants to create ever-evolving narratives.

The Instrument of Troubled Dreams, 2018

Emotional Architecture

Sound sculptures, as developed by the Canadian duo, are not objects but an acoustic event that transforms the architectural space into a living one. For decades, their works have inhabited space in a sensory and emotional way, but also from a structural perspective, questioning the ways in which an art installation can, by occupying a space, revive it while simultaneously care for it.

It turns out that at this moment, this act of reanimating the architecture faces an imminent threat: the possible transformation of the monastery into a luxury hotel. What happens when heritage becomes a commodity? When the aura of a place becomes experience-driven marketing? It is from this tension, between occupation and care, resonance and gentrification, preservation and market, memory and capital, that Anozero’25 Coimbra emerges. And how can we imagine forms of permanence that aren’t dependent on immediate profit? For The Factory of Shadows, Cardiff and Bures Miller, together with the directors—architect Carlos Antunes and Désirée Pedro—have selected works that appeal to memory and listening, offering a different temporality, one in which value is not immediate nor transactional, but relational.

To Touch, 1993. Cortesía de les artistas

The Monastery as Possibility

As Sara Ahmed[3]Sara Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion, Edinburgh University Press, 2004. Available online here. writes, spaces are not neutral: they affect us, they orient us. The art of Cardiff and Bures Miller moves within this affective dimension. Their installations slow down time, demand physical presence and prolonged listening. They cannot be consumed quickly. That, in itself, is their form of resistance. Still, the ghosts of cancelled futures haunt the Monastery. Will this space continue to resonate with art, or will it fall silent under the weight of five-star comfort? Art may not save buildings, but it can remind us what they were for, or who once lived within them. In doing so, it may propose new forms of preservation, not by holding them in stasis, but through affective, communal, and situated transformation.

Exterior del Monasterio de Santa Clara-a-Nova en Coimbra

The Infinity Machine, 2015

[Featured imahe: The Forty Part Motet, 2001, Janet Cardiff]

All images: The Factory of Shadows, Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller. Mosteiro de Santa Clara-a-Nova, Coimbra (Portugal), 2025. Courtesy of Anozero – Bienal de Coimbra, 2025 © Jorge das Neves

The Factory of Shadows: Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller at the Mosteiro de Santa Clara-a-Nova in Coimbra, Portugal, until July 5.

Curated by the Círculo de Artes Plásticas de Coimbra.

| ↑1 | Jean-Luc Nancy, À l’écoute, Paris: Galilée, 2002. Translated into English as Listening, trans. Charlotte Mandell, New York: Fordham University Press, 2007. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Mark Fisher, Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures, Zero Books, 2014. Available on line here. |

| ↑3 | Sara Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion, Edinburgh University Press, 2004. Available online here. |

María Muñoz-Martínez is a cultural worker and educator trained in Art History and Telecommunications Engineering, this hybridity is part of her nature. She has taught “Art History of the first half of the 20th century” at ESDI and currently teaches the subject “Art in the global context” in the Master of Cultural Management IL3 at the University of Barcelona. In addition, while living between Berlin and Barcelona, she is a regular contributor to different media, writing about art and culture and emphasising the confluence between art, society/politics and technology. She is passionate about the moving image, electronically generated music and digital media.

Portrait: Sebastian Busse

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)