Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Before the performance begins, the atmosphere carries a different charge, far removed from the usual solemnity of opera. Marina Abramović presents Balkan Erotic Epic, not a spectacle so much as a pagan liturgy displaced— not without friction—into the heart of a bourgeois institution. At the Gran Teatre del Liceu, the historic temple of opera and classical representation, the Serbian artist unfolds a collective ritual that exceeds the stage format to become a choral, sensory experience. For more than three hours, the theatre ceases to be a site of passive contemplation and transforms into a space traversed by corporeality, chants, suffering (a great deal of it), music, and rituals.

Marina Abramović, a key figure in the institutional legitimisation of performance art, now almost 80 years old, withdraws her own anatomy to assume the ambiguous role of high priestess. The work she has conceived, designed, and directed leads a chorus of anonymous bodies that embody myths and ancestral cults drawn from Balkan mythology—some dating back to the 9th and 10th centuries—crossing geographies and cultures from Romania, Bulgaria, Albania, Serbia, Bosnia, Kosovo, Montenegro, and North Macedonia to Greece and Turkey, alongside Roma and nomadic traditions. Her gaze avoids nostalgia; it is archaeological, political, and profoundly telluric. The body becomes a living archive, a surface upon which memories erased by war, religion, communism, or sanitised modernity are inscribed.

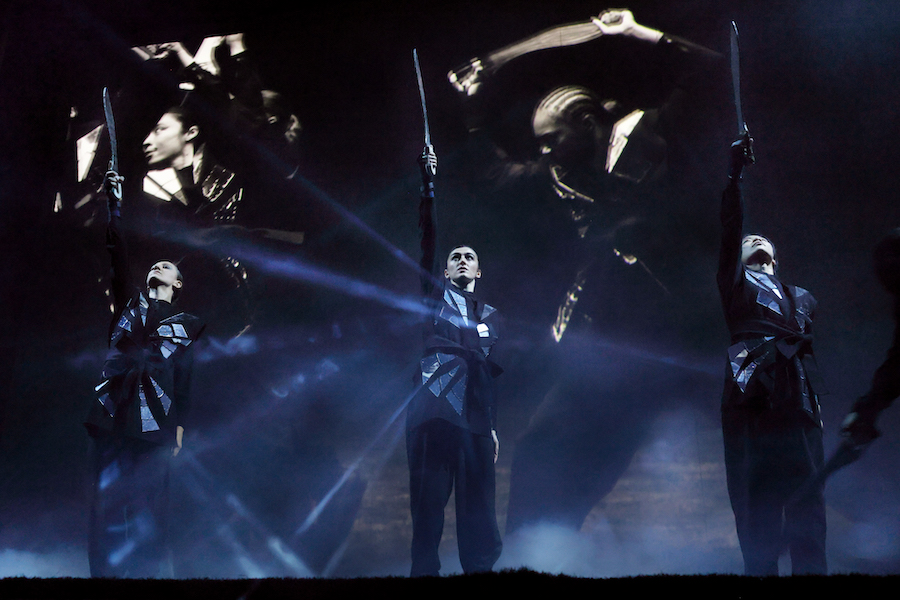

Originally premiered in Manchester with 70 performers activating all scenes simultaneously, the version presented in Barcelona is a condensed theatrical adaptation, featuring 34 performers across 11 consecutive scenes. Far from weakening the work, this reduction intensifies its choreographic dimension, shifting the focus from excess to a more concentrated corporeal density and underscoring the idea of Gesamtkunstwerk: dramaturgy and humour, dance, performance, live Balkan folk music alongside electronics, audiovisual projections, and animation intertwine within a fluid structure.

Among the public, in the corridor leading to the stage, a percussion and brass band appears, followed by Danica Abramović, the artist’s mother. The performance opens with a long funerary lament for Josip Broz Tito. More than a tribute, it is a mourning for a vanished world—the dream of a multicultural Yugoslavia—and an acknowledgment that every epic always begins with a loss. Danica, rigid and uniformed, lays down flowers. She embodies the conservatism the artist seeks to exorcise. From this point onward, Balkan Erotic Epic unfolds as an epic without heroes: what is narrated are not individual feats, but communal ceremonies of survival.

Each scene functions as a station in a deeply atavistic liturgical itinerary: women exposing their vaginas to the sky to stop the rain and save the harvest; a knife dance performed by burrneshas—women who swear chastity and assume male roles as heads of households. This tradition, primarily Albanian but also present in Kosovo and Montenegro, has been explored in cinema in films such as Burrnesha (2015) by Laura Bispuri, a powerful reflection on gender identity and power in the Balkans. The work continues with male guttural chants in which virility is exposed as fragility; funerary weddings that unite love and death; scenes of mourning where eroticism functions as a language through which to dialogue with the absent; and a tavern—the kafana—where historical enemies dance together, and a homoerotic relationship suggests the possibility of desire between Balkan nations traditionally set against one another. The fertility of Mother Earth and her generative force runs through the entire work as an active principle, recognising in (male) orgasm a form of offering, and in the scream a form of prayer.

The thunderous appearances of the band onstage resonate with the festive and funerary chaos of Underground (1995), whose soundtrack unleashes the energy of Goran Bregović’s music. Directed by Emir Kusturica, the film premiered during the Balkan wars that led to the dissolution of Yugoslavia. As in the film, the band —with its brass and percussion— appears and disappears throughout the acts, moving between the grotesque, the sacred, and the carnivalesque, establishing a cultural echo that directly connects with Abramović’s staging.

Visually, the apparatus reinforces the ritual dimension of the work. A large mobile screen that rises and falls, dividing the stage, projects videos directed by Nabil Elderkin. The images—sometimes in slow motion, sometimes in black and white—introduce a suspended, almost hypnotic temporality that dialogues with the music and mirrors the movements on stage, creating a duality between presence and reflection, action and reverberation.

Balkan Erotic Epic builds a bridge between the ancestral and the contemporary, between myth and politics, between collective memory and individual intimacy. Every gesture, movement, and sound seems to summon a past buried beneath progress, reminding us that violence, death, love, and desire are inseparable from Balkan culture. The piece is an epic of bodily gestures, but also of time and memory: a descent into the sacred and the carnal that probes beyond representation to examine what reactions these ceremonies provoke when activated in the present. Rather than a return to an origin, the work awakens a latent energy that, once activated, puts into crisis— and not always comfortably—our contemporary ways of looking at and inhabiting corporeal nudity.

In this context, nudity ceases to be provocation and becomes a poetic language. The artist questions the notion of obscenity as a form of separation: “obscenity is born from taboo, from the distance between body and spirit,” which here recovers its sacred and telluric dimension, becoming a surface of collective inscription, while eroticism reveals itself as a bond deeply rooted in the earth and in shared experience.

Epilogue

The relevance of this work also aligns organically with the close of A*DESK’s January 2026 editorial month on the new wave of women filmmakers in the Balkans, edited by Besa Luci. Abramović not only revives historical memories and rituals; she also articulates a high-voltage feminist language in which female bodies are empowered by celebrating sexuality as resistance and affirmation against structures of power—both historical and those of our regressive present.

All photographs © Marco Anelli Studio, @marco_anelli_studio. Courtesy of the Liceu Barcelona.

Balkan Erotic Epic by Marina Abramović at the Gran Teatre del Liceu, until 30 January.

María Muñoz-Martínez is a cultural worker and educator trained in Art History and Telecommunications Engineering, this hybridity is part of her nature. She has taught “Art History of the first half of the 20th century” at ESDI and currently teaches the subject “Art in the global context” in the Master of Cultural Management IL3 at the University of Barcelona. In addition, while living between Berlin and Barcelona, she is a regular contributor to different media, writing about art and culture and emphasising the confluence between art, society/politics and technology. She is passionate about the moving image, electronically generated music and digital media.

Portrait: Sebastian Busse

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)