Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Aby Warburg (1866-1929) was a disruptive name in 19th century academia. The historian of art and culture called on a critique of visual arts far removed from the historicist stylistic and formal debates of his time. A Lecture on Serpent Ritual (1923), his farewell address from the Kreuzlingen psychiatric clinic where he had been committed, is one of his fundamental works. There, he formulated the tenets of an iconology connected to vital forces whereby the images of the past return to the present. Through his research he forwarded a fragmentary, cross-disciplinary thought which allowed him to make sense of art from an innovative perspective as a series of institutional practices establishing a given object as of cultural interest. In that sense, according to his perspective how and under which conditions images persist through time.

With the Mnemosyne Atlas, Warburg’s final project, his main lines of work come into being, named after the Titanide of Greek mythology Mnemosyne, daughter of Gaia and Uranus. In addition to her being mother to the nine Muses she became known for her allegorical association with memory (her name’s philological origin in Ancient Greek, mnêmē, means “memory”). Until his death, the scholar collected graphic material in order to put together an image book that would account for themes, patterns and visual signs in Western culture from ancient times to the Renaissance and beyond. Warburg created thus an iconographic method of his own, one which introduced the concepts of “survival” (Nachleben) and “formulae of pathos” (Pathosformeln) in the history of art, culture and philosophy to this day.

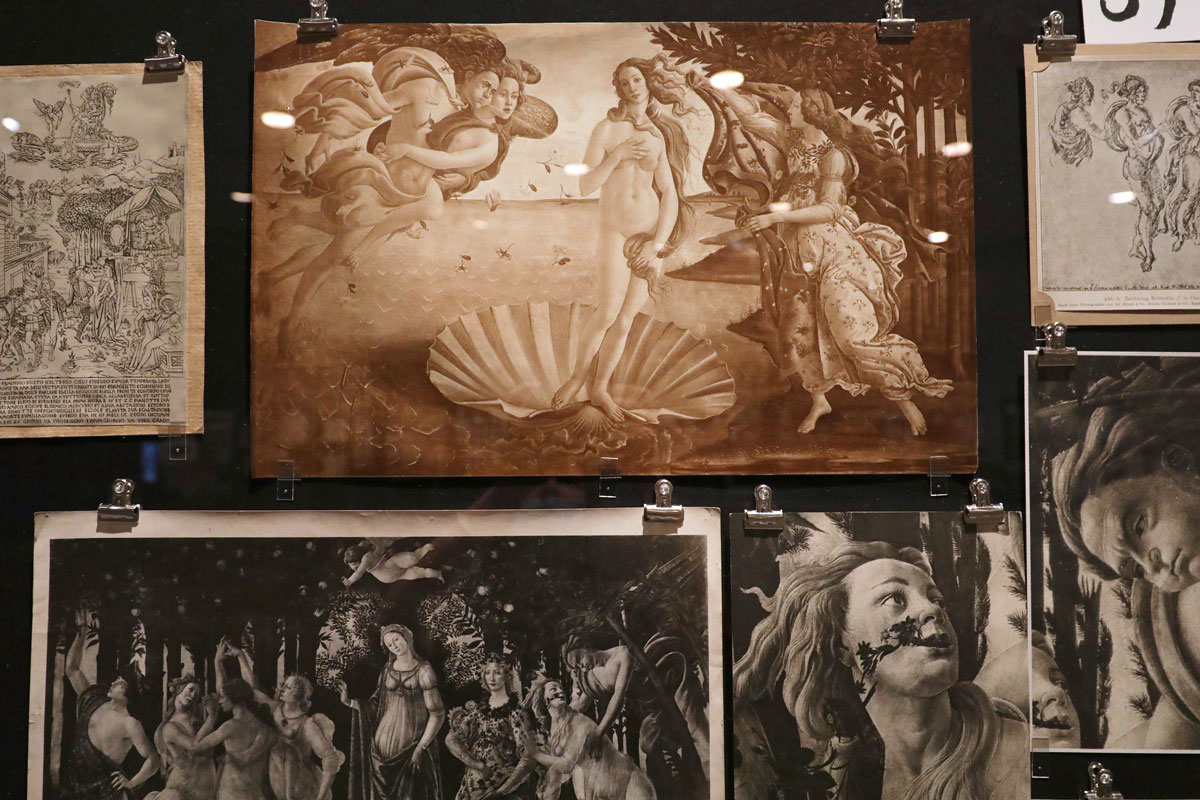

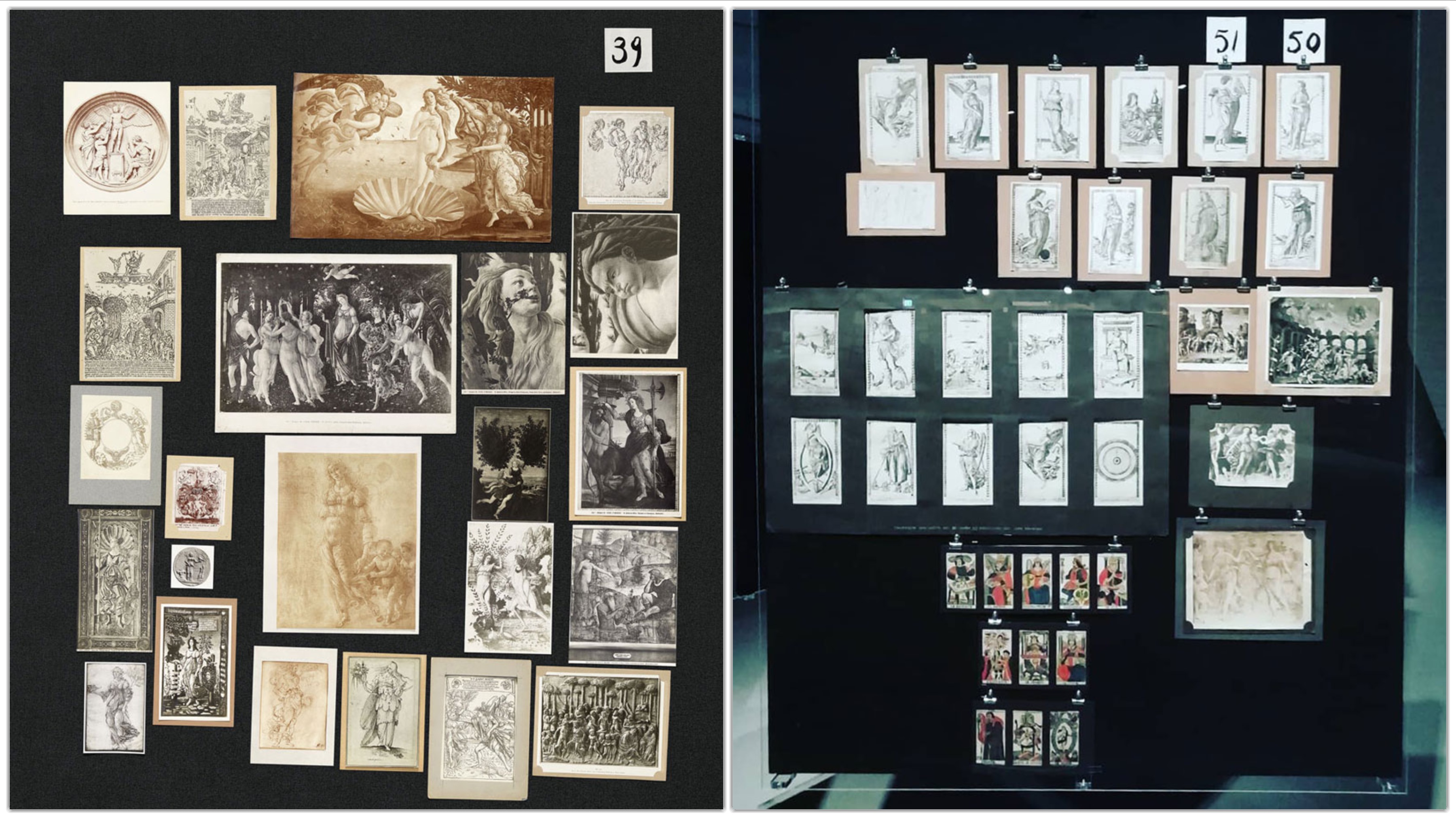

On movable blackboards, the historian attached photographic reproductions of works of art from the East, classical antiquity and the Renaissance alongside advertisement cut-outs and contemporary photographs, in order to reveal their common graphical patterns. And, in this way, the researcher and his team studied the forms and the network of relations of images, drawing an open cartography, a form of knowledge by assembly. A methodological alternative which called into question the difficulties art historians had ascribed to images as vehicles of representation.

Assembly bestowed flexibility on Warburg, and thus he was able to switch from the Spring and The Birth of Venus by Sandro Botticelli to the traces of Antiquity in the frescoes and the astral signs crowned by pagan gods in the Palazzo Schifanoia.

The exhibition Aby Warburg: Atlas Mnemosyne: Das Original can be visited From September 4 to November 30, curated by Robert Ohrt and Alex Heil in partnership with the Warburg Institute in London, at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt. For the first time, the original panels and documents have been gathered in their entirety, concentrically distributed at Ausstellungshalle 1.

The itinerary also includes an important, felicitous decision by the curators: a section focusing on the research team attending Warburg in his daunting task until the year he died. Fritz Saxl and Gertrud Bing rescued their master’s work from Nazism and relocated his vast library (60,000 books and 15,000 photographs) from Hamburg to London, where the Warburg Institute would be subsequently created.

The aesthetic outlines found in the more than 1000 images in the almost 80 exhibition panels take us through the visual constellations Warburg intended to set forth. The blackboards are numbered, making up thematic series. The first one is marked from A to C, corresponding to the introduction to the Atlas, and containing maps of Europe and Mesopotamia, depictions of the solar system, astral charts and the photographic reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. In this manner, his approach lays down the “surviving” forms, places and figures, throughout an outline of nearly 3000 years of images.

In the series The Rebirth of Antiquity (Die Wiedergeburt der Antike – die Jahre 1400 – 1600 nach Christus), his passion for the Italian Renaissance is noticeable. The reproductions of The Birth of Venus and the Spring by Sandro Botticelli are shown in different sizes, details and clippings from the different characters making up both works. In his book The rebirth of paganism, Aby Warburg engages in dialogue with several texts in order to analyse the work of the Italian artist and restore the vitality and the movement of the gestures.

Charts devoted to Andrea Mantegna, Claude Manet and Albrecht Dürer contain the study of historical tarot packs and the permanence of images such as the Mantegna Tarocchi (Ferrara, 15th century), Jean Dodal’s (Lyon, 18th century) and Jean Payen’s (Avignon, 18th century) decks can be seen. However, the German historian didn’t leave any written text to map the pathway of his Atlas which, just like the tarot cards, invites us to a fragmentary and open journey into Arcanum 21, the World.

Verónica Elizondo has a doctorate in theory of literature and comparative literature from the Autonomous University of Barcelona. In addition, she has a post-doctorate in Gender Studies from the University of Buenos Aires. She is based in Berlin where she collaborates in different media. Her research works deal with areas such as Latin American literature, cultural studies, with special dedication to gender studies.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)