Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Alonso Berruguete knew about the fire of Medina del Campo during the years in which he started to stand out as the grand sculptor of his time. That fire that took place in 1520, was a military action of the comuneros that destroyed the village and sparked off the Revolt of the Comuneros. It was a period of conflict and hunger, of Inquisition and of auto-da-fé. After a life dedicated to the innovation in the sculpture of saints, virgins and Christs, the fire of the eyes of Berruguete put out in September of 1561, in Valladolid, the year and the month of the worst fire ever seen in the city, that lasted 50 hours and scorched almost five thousand homes. Some religious blamed a group of Lutherans for causing the flames, accusing them to take revenge of the auto-da-fé of 1559, during which 27 people were burned, and the statue of another, in front of the attentive look of the king.

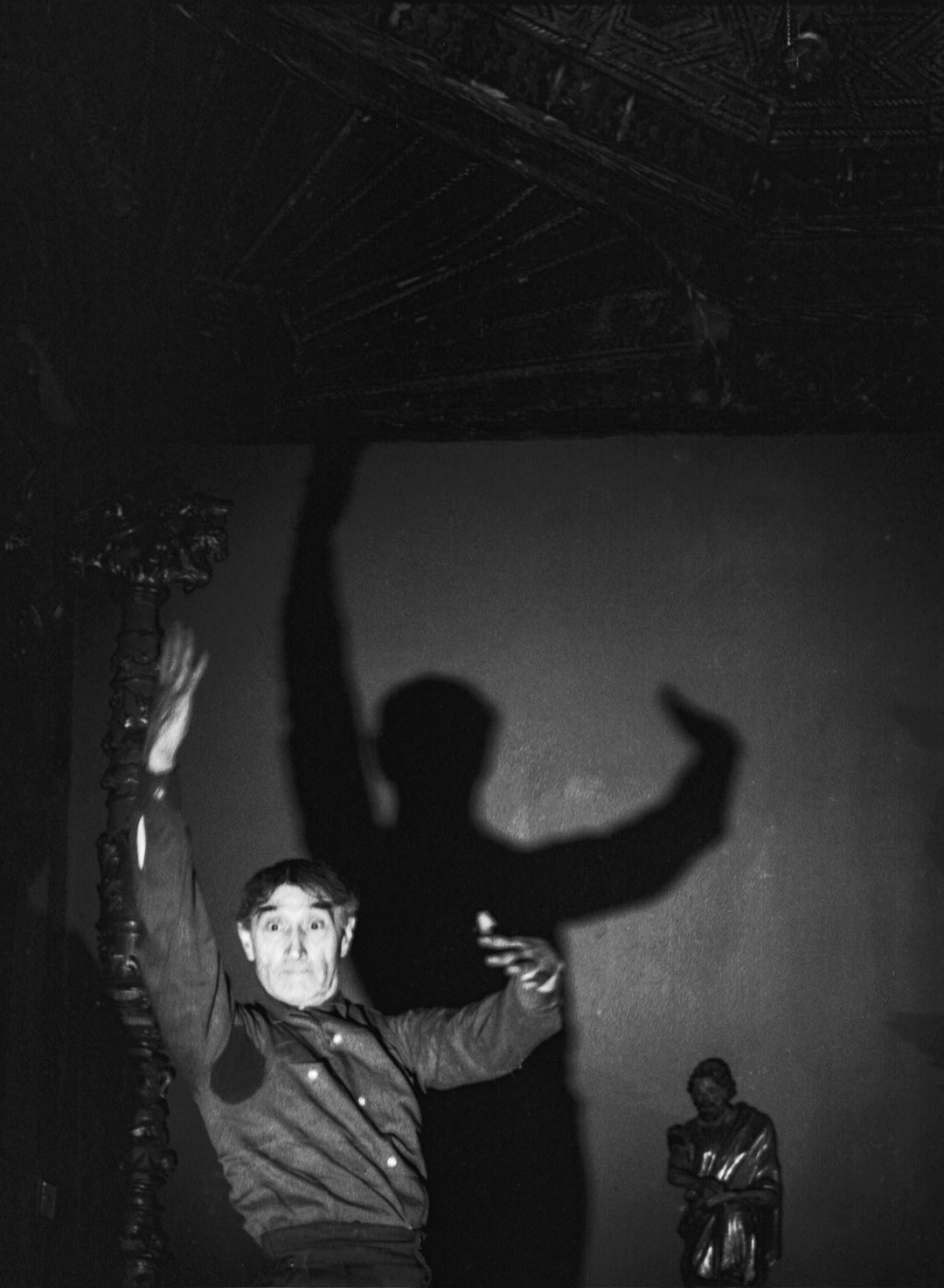

Four hundred years later, another fire, this one artistic, lighted up the great works of Alonso Berruguete during the nights of hunger and the underdevelopment of the fifties in Valladolid. The film-maker from Granada, Val del Omar, and the flamenco dancer from Valladolid, Vicente Escudero, filmed during several nights, between 1957 and 1960, scenes of dancing and passion in front of the works of the Renaissance. From that shooting emerged “Fuego en Castilla. Tactilvisión del páramo del espanto” (Fire in Castile [Tactil Vision of the Wasteland of the Fear]), as part of the “Elementary Triptych of Spain” with which Val del Omar won the prize in Cannes in 1962. The encounter of these two creators and the sculptures of the Museum of Sculpture sparked off: Vicente Escudero, with one leg in La Vanguardia and the other in the flamenco, he was inspired by Berruguete, just as the French dancer, Serge Lifar [1], did. José Val del Omar, the mecamysticinventor that, with his set of lights and shadows made the apostles of Berruguete dance. In the palpitating images (what we call nowadays stopmotion) of “Fuego en Castilla” (Fire in Castile) we see the sculptures alive, interweaving their ecstatic looks with the obedient dolls of Escudero, while the trellis latticed float on top of the outline of the harassed. Vicente Escudero declared that flamenco dance was for him “a flame”, and that he searched in it, through lines and movements, “a satisfaction of fire”. In this work, Val del Omar experimented with lines and movements, and also with the sound: the tap-dancing of Vicente Escudero sets the pace mixing under a same pattern the drums of the procession of Easter Week. Overexposures of ages, techniques and wishes under the same burning heat.

Photography by Filadelfio González. Courtesy of the National Museum of Sculpture of Valladolid.

The film in 35mm, the tap-dancing, the shadows, the sculptures fit together in an exhibit at the National Museum of Sculpture of Valladolid, under the title “José Val del Omar and Vicente Escudero: a somnambulist dialogue” and the commission of Juan Carlos Quindós. A hall is enough to call those sunrises of improvisation and conviction, showing “Fuego en Castilla” (Fire in Castile) surrounded by the main sculptures, and photographs taken by Escudero and Val del Omar never shown before, authorship of Filadelfo González. The article that Diario Regional (Regional Newspaper) published on the 30thof March of 1957 is reproduced for the exhibition. Its title is “A ghost visits the Sculpture Museum”, done with the collaboration between the Andalusian film-maker and the local dancer, who are described as “the shadow of the ghost that visits the Museum and that gets surprised for what is there”. This astonishment is now shared for the spectators of the 21stcentury, witnesses through several invocations [2] of the labour of whom was darkened during the Francoism, perhaps for his facet as a teacher at Misiones Pedagógicas during the Second Republic. Regarding the work of Val del Omar, Jean Cocteau said: “In Spain everything ripples and flames up. The flamenco dance itself is a flame that flamenco dancers try to put out. In flamenco everything is a coordination of movements with a united sense. A coordination of personal attitudes facing a common fire that wants to devour it. Burnt down, dancing is itself a way of putting down this fire. Walking on flames, slapping their muscles, in the body, wherever those flames arise”. The phantasmagorical stomping crackle of “Fuego en Castilla” (Fire in Castile) revives the embers of a Spain of genius and shadows. Time passes by, shadows pass by, but the flames keep rippling.

[1] Who said that “In Berruguete there is the seed of an incredible ballet. Which hand, which technical inspiration can encourage these burning logs in this divine farce?”

[2] From the Museo Reina Sofía (2010) to the Bienal of Sao Paulo (2014)

His intention is to continue to improve his writing of art criticism; everything else is enjoying and learning from contemporary proposals, establishing other strategies of relations, either as a contributor to magazines, editor of a review, curator or lecturer. As a backpacking art critic, he has shared moments with artists from Central America, Mexico and Chile. And the list will continue. Combating self-interested art, applauding interesting art.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)