Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

The Berlinale is experiencing turbulent times. In last year’s edition, several filmmakers withdrew their films from the program due to its alleged complicity with the State of Israel. Additionally, the double victory of the documentary No Other Land (Panorama Audience Award for Best Documentary Film and Documentary Film Award) led various German political bodies to pressure the festival into distancing itself from the film’s perspective on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. At the time, the festival’s director, Mariëtte Rissenbeek, was forced to call the speech given by the documentary’s co-directors, Yuval Abraham (Israel) and Basel Adra (Palestine), “inappropriate” and urged other filmmakers to remain impartial.

The dismissal of an employee for signing an internal email with “from the river to the sea” was the final trigger that led to a boycott promoted by PACBI (the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel) and the creation of a parallel festival called Palinale. Through screenings, music, talks, and exhibitions, Palinale aims to foster dialogue on Palestinian liberation and resistance against the oppression of marginalized peoples and dissident voices. Initially, I insisted that it would be better to focus solely on this program and support PACBI.

A boycott is an action designed to destabilize a person or entity and force change. The climate of fear instilled in the German cultural sector—fueled by political and police repression of pro-Palestinian and anti-genocide discourse—made it impossible for Palinale to function as a true boycott. This became evident from the festival’s opening panel, where guests struggled to agree on the event’s purpose, alternating between arguments for and against participating (as professionals or spectators) in the Berlinale. However, Palinale did succeed in becoming a safe space for debate.

Film screaning ‘Eccomi…Eccoti’ during Palinale. © Matías Daporta / Palinale 2025

During one of the post-screening discussions on intersectionality in struggle, an audience member spoke up about the challenge of discomfort. They described how the discomfort inherent in activism is indistinguishable from what they experience daily, having been born in a conflict-ridden nation, Syria, and being a migrant in Germany. In contrast, they pointed out that white and European communities, thanks to their privilege, can choose when to engage with a cause, stepping in and out without it affecting their daily lives.

Tilda Swinton was the recipient of the Berlinale’s honorary award this year, in a strategic decision by the festival’s newly appointed director, Tricia Tuttle (United Kingdom). Through a carefully curated selection of projects, Swinton has garnered recognition from the most avant-garde sectors of culture, establishing herself as a figure associated with progressive politics. She was the perfect face to restore the festival’s questioned reputation.

In her speeches, Swinton eloquently spoke about dissent and resistance, revealing the utopia she believes we should aspire to live in: the so-called “Independent State of Cinema”, a place immune to occupation, colonization, persecution, and deportation. Her speech avoided specific references or direct mentions of ongoing conflicts, ensuring unanimous applause. During the press conference, Swinton stated that the festival’s organization had given her full freedom of expression, reinforcing the idea that the Berlinale is a space for free speech.

However, subsequent events revealed a certain naïveté or inability on Swinton’s part to grasp the context in which she was speaking. This exposed her interventions as an exercise in performative activism—driven more by a desire for recognition within that Independent State of Cinema than by a genuine commitment to the current situation. By refraining from naming specific figures or agents and remaining on a purely symbolic level, she avoided the discomfort that is intrinsic to any truly transformative political action.

Palinale was closer to being that Independent State of Cinema than the Berlinale. At Palinale, I could wear a kufiya (a traditional Middle Eastern scarf, emblematic of the Palestinian community) without being questioned; at the Berlinale, wearing it exposed me to intimidating and disapproving looks. Several participants expressed a similar discomfort in their speeches. For instance, during the presentation of Queer Panorama, director Jun Li, reading a statement on behalf of his actor Erfan Shekarriz, had to endure boos and racist remarks. Similar situations recurred throughout the festival, making the final words of Jun Li’s speech resonate even more: “No one is free until everyone is free.”

The Berlinale’s lack of a clear stance creates an uneasy contradiction within its programming. Many of the films screened take explicit stands against fascism, in favor of sexual and gender diversity, and celebrate interculturality. Yet, these choices seem more like a superficial gesture of distancing from Europe’s colonial, classist, and racist reality rather than an authentic attempt to challenge the structures that perpetuate this legacy and shape today’s global socio-political landscape.

The Berlinale following the logic developed by bell hooks in Eating the Other regarding the exoticization and symbolic consumption of alterity. It appears to fall into the trap of using diversity as the key “seasoning” to craft a progressive narrative that differentiates it from other festivals of similar scale and relevance, such as Cannes, San Sebastián, or Venice.

It is an analogous exercise—just as hooks suggests—to the desire to “sleep with” as much diversity as possible. I even fell for the allure of that diversity. Although I had initially decided to focus exclusively on the Palinale program, I ended up attending both festivals interchangeably—not out of necessity, but out of desire (for attention, prestige, consumption, knowledge, recognition, etc.).

Palinale’s goal moves away from all this, inviting us to inhabit discomfort. By offering a program imbued with politics and presented on a platter of values, it manages to activate and collectivize struggle. Its screenings push us to abandon the passivity of individualist discourse and embrace action and conflict as a collective… And it succeeds, but only to a certain extent.

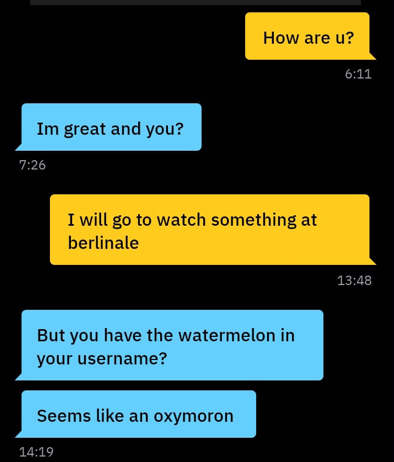

I am a case of cultural scabbing. Several friends confronted me for not sticking to my original plan. Even strangers on Grindr, the gay dating app, called out my inconsistency for displaying a watermelon emoji—a symbol of solidarity with Palestine—on my profile while enjoying the Berlinale.

Conversation in the dating application Grindr © Matías Daporta / 2025

I made choices from a place of privilege, hiding behind a weak logic that justified my actions by questioning Palinale‘s lack of clear definition instead of understanding its complexity. I allowed myself to be seduced by the Berlinale’s marketing, betraying my own ethics. After this experience, I find it hard to believe in the ability of cultural activism to provoke real change without the active involvement of institutions.

The Berlinale has the prestige necessary to be an agent of change—if its leadership were willing to take the risk of prioritizing human rights over its own interests, even if that meant jeopardizing the festival’s stability. Merely programming films with political messages is not enough; actively supporting those messages and their creators is essential, especially for a festival that prides itself on having politics in its DNA.

Or perhaps this is just another excuse to justify being a scab at the Berlinale.

(Cover photo: Tilda Swinton during her speech at the Golden Bear Award Ceremony © Richard Hübner / Berlinale 2025)

Matías Daporta is an artist, curator and cultural manager with a transdisciplinary approach. His work encompasses artistic and curatorial projects that explore the limits of cultural law, cultural homogenisation, the intersection between live arts and other artistic disciplines (and life itself) and the visibility of queer identities. His projects, whether artistic or curatorial, seek to generate a social context that proposes new mechanisms of attention and observation of an event. Daporta curated Me gustas pixelad_, on the intersection between performance and digital culture at La Casa Encendida; the European project Digital Leap, for the Institut Ramon Llull; or the mediation project Framing Intimacy for the Joan Miró Foundation. He also established DESFOGA in 2014 (active), a residency and festival programme aimed at addressing power dynamics, inequalities and human rights violations through performances, installations and exhibitions.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)