Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Matters related to landscape have been widely described, discussed, and exhibited in Chile. In the nineteenth century, traveling European scientists, draftsmen, illustrators and artists explored our territory –and in some cases, made it their own– laying the foundations for the subsequent development of landscape painting.[1]

This scenario gave birth to bucolic paintings, engravings and lithographs by the likes of Claudio Gay, Alejandro Ciccarelli, Antonio Smith and Onofre Jarpa, all involved in a purely romantic and scientific practice. However, already in the previous century and quite frequently since the beginning of the current one, there has been a vision of the landscape that drastically questions some of the most recognizable and canonical postcards regarding this subject.

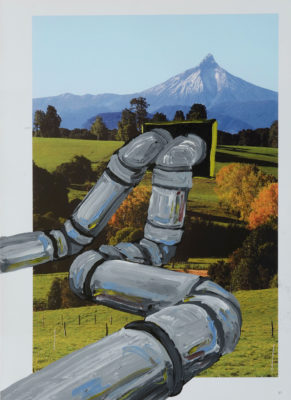

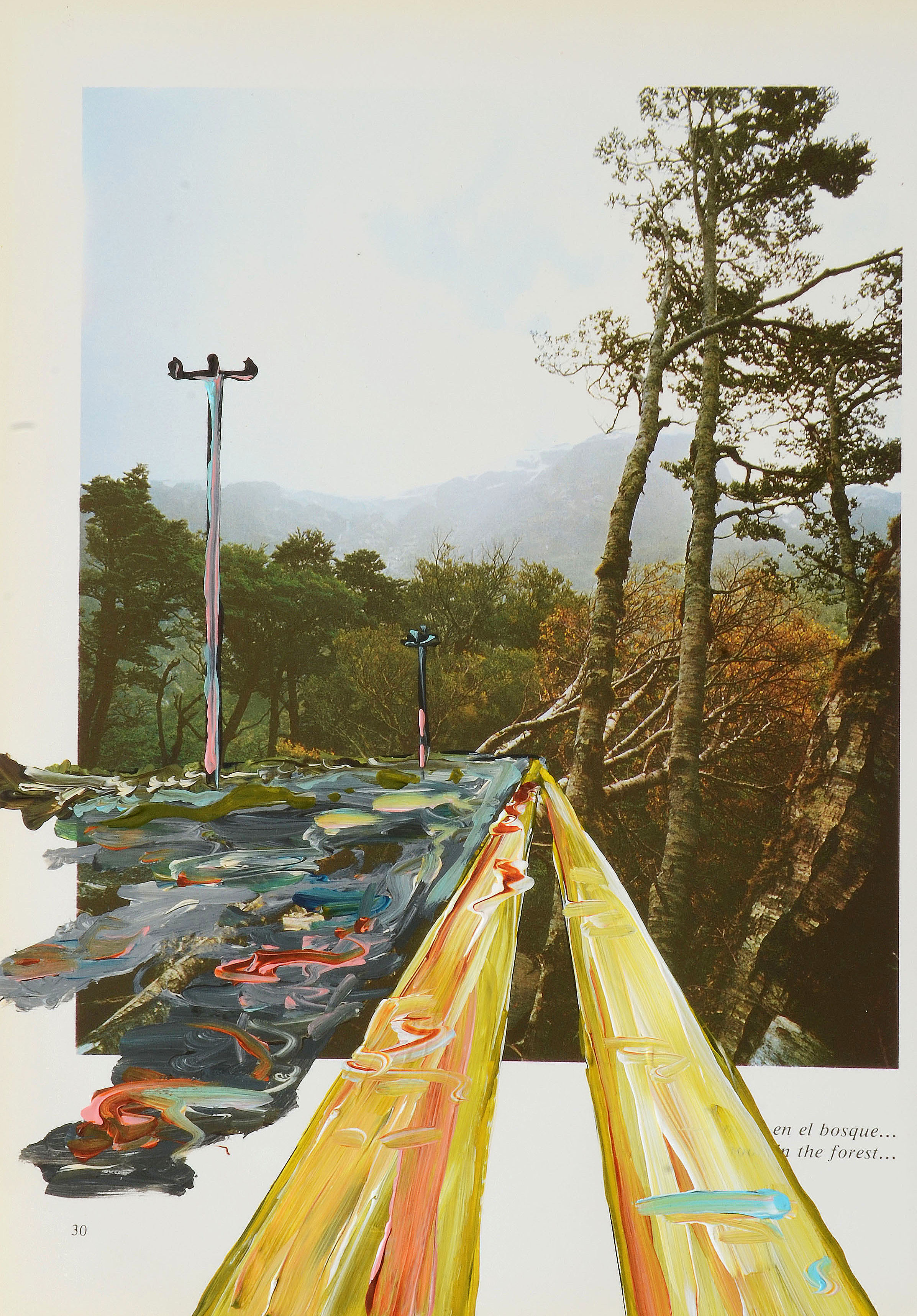

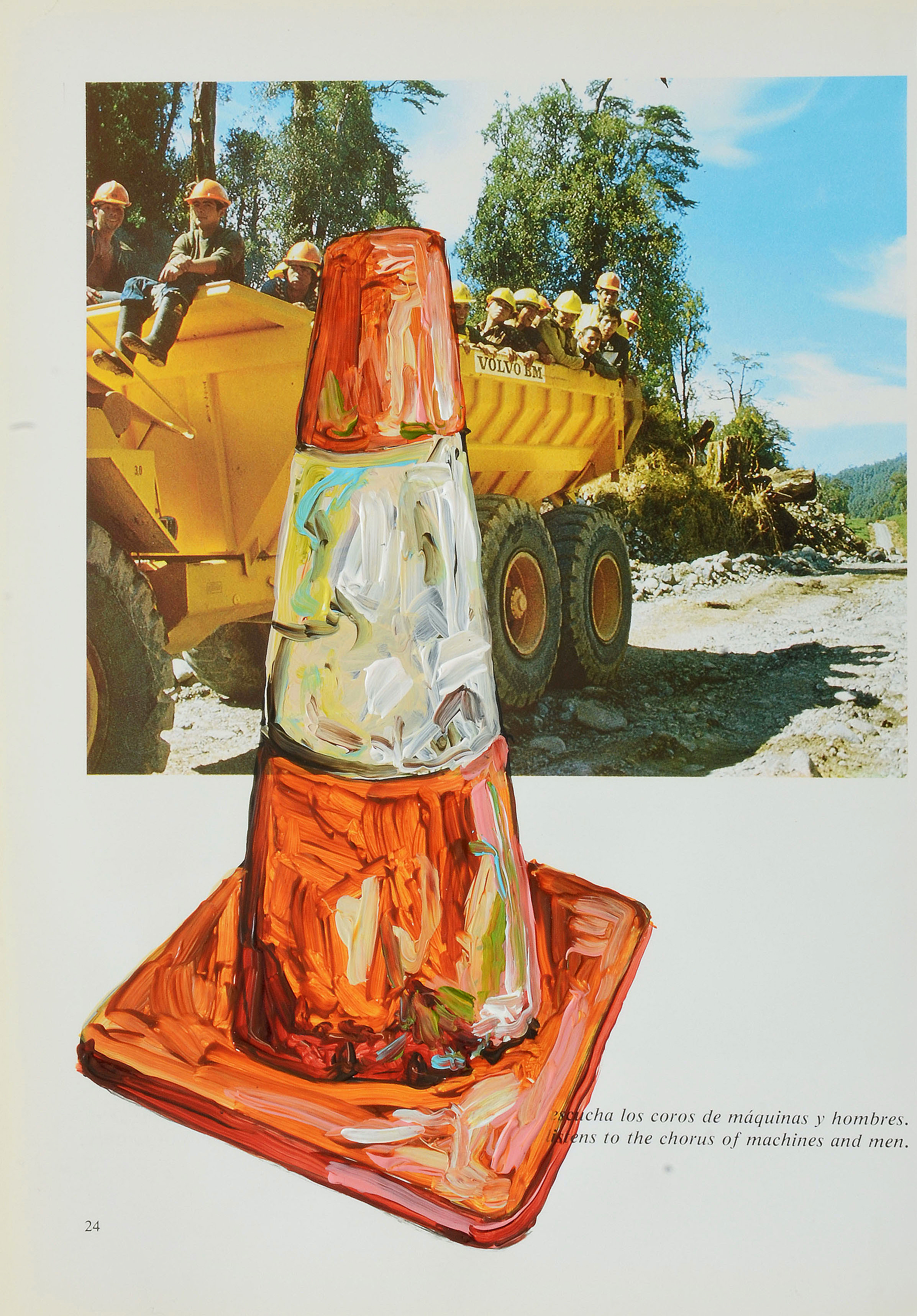

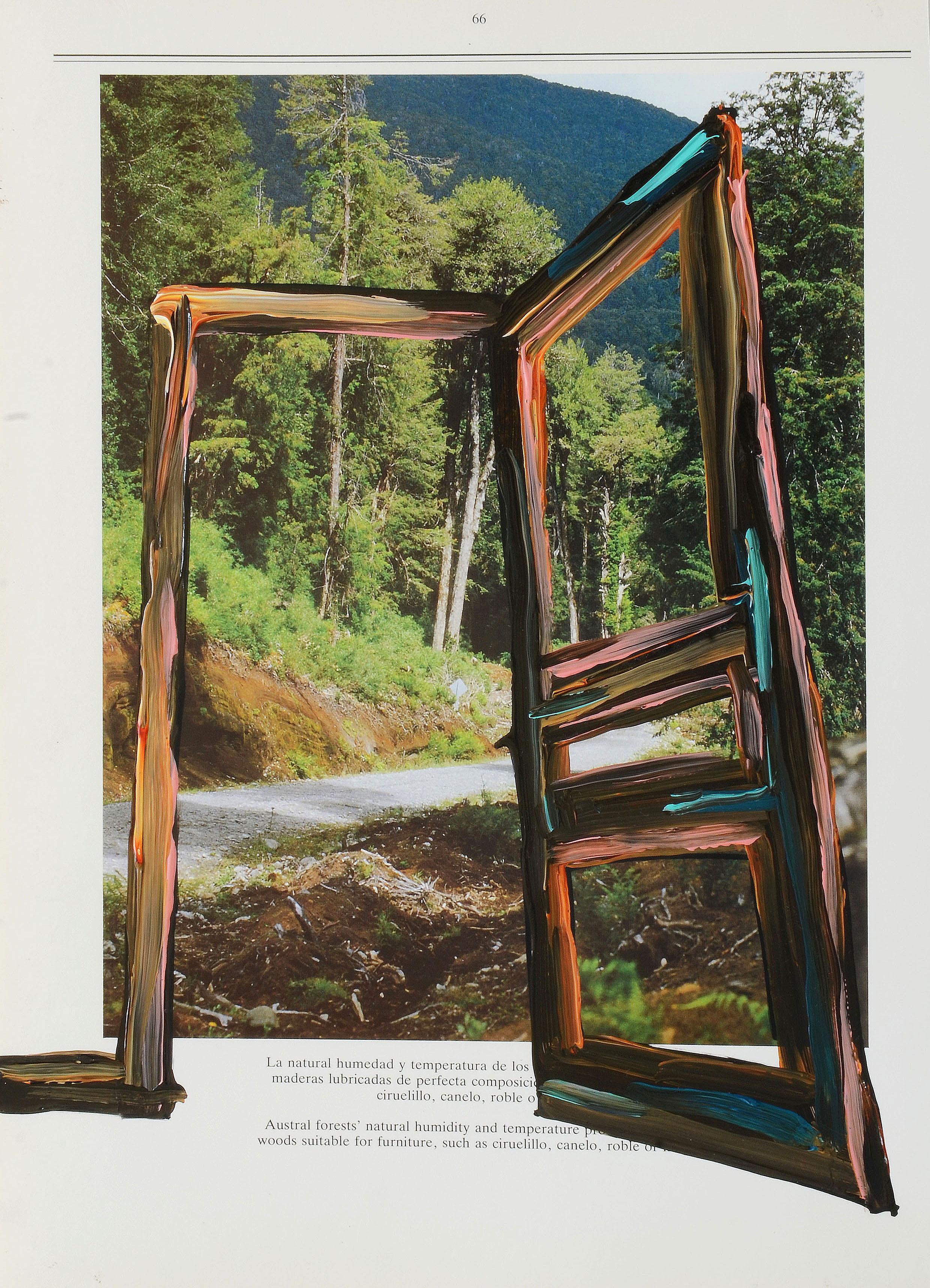

Hand in hand with these insurgent ideas, visual artist Germán Tagle proposes a series of images that reflect, based on a detailed disarticulation of nineteenth century painting and its schemes, on the current degradation suffered by the different ecological floors as a result of humanity’s geological force, a fact resulting in an undeniable deterioration of the landscape.

We should not forget that nowadays artists are expected to address issues of public concern. Currently, the democratic public seeks in art the representations of issues, subjects, political controversies and social aspirations activating our daily life.[2] In this sense, there is a planetary yearning that draws on Tagle’s critical and insightful conscience to be one of the many to present on the world stage part of the history of evident ecocides burdening this country. In addition, these perspectives pose a collective introspection on the actions that should be shared by the visual arts in order to design an urgent and strict defense of the ecosystem.

Throughout 2020, we have witnessed the heartbreaking banners that confront us with the reality of climate change, deforestation, and a multi-continental epistemic crisis. Points of convergence inviting us to reconsider our agreements with the vital elements that the Pacha[3], provides, many of which we have constantly looted, altered and, mainly, extracted. No one can deny that extractivism is a system that favors the annihilation of landscapes where flora and fauna coexist, and that extractivism has turned out to be a violent and destructive economic development model for the ecological balance of the world. According to MODATIMA (Movement for the Defense of Access to Water, Land and the Protection of the Environment), Chile is renowned for fostering a model of irrational and massive appropriation and exploitation of common natural goods, without their processing or with minimal processing, generally destined for export markets.[4]

Under this perspective, the problems that are currently being revealed by the changing landscapes are due to an indiscriminate extractivism of natural resources.

For extractivism, everything is transformed into a resource to be extracted and sold as a commodity in order to gain excessive profits in the global market. This includes life forms (human and non-human) and even certain ritualized cultural artifacts from bygone times. All of these are seen as instruments for sustaining an extractivist life, which additionally depoliticizes, decontextualizes and strips away the linguistic and cultural meanings that coexist with the extracted artifacts and objects.[5]

Thus, the machinery of extractivism is the great inspiration behind these pictorial reflections in order to re-visit and re-explore those geographies contaminated by certain intermediaries, bursting into the postcards promoting congenital landscapes. High voltage towers, pipelines, household artifacts and capital’s own waste are agents that, loaded with human waste, evidence other appearances that coexist with our eco-territories.

On the other hand, these pictorial intersections end up in a couple of specific locations –by now quite recognizable– that reveal the variations of an environment that is increasingly corrupted by neoliberalism. In this way, the extractivist equation that Tagle is offering, a mark of the depredation of nature, is precisely focused on opening a harsh dialogue for examining the production and distribution of resources, for there is no production without extraction within neoliberalism, and not even a sustainable proposal within the same extraction process, especially in these months when we coexist in the face of widespread uncertainty.

The magnifying glass of neoliberalism would like these landscapes to be equated with consumer goods. It is the logic of an outdated system in a time of unprecedented economic recession and civic depression. A situation that is part of this environmental analysis that Germán Tagle has focused on the natural environments already annoyed by the irruption of transnationals, inspiring here a pictorial reflection on the deformations suffered by the landscape.

At the same time, the particular link between a couple of pictorial landmarks and the explicit territorial diversity, constitute a key axis for comprehending the peculiar making of these images. Certainly, these paintings and installations manipulate the environment, which has already alerted us to the precarious management and the social, political and economic irresponsibility sustained by humanity.

Specifically, these images are the result of a tension between extractivism and the landscapes that the artist has (re)constructed and (re)produced throughout his career. An uninterrupted dialectic between his form of art production and the textures intertwined with a sustainable notion, stressing the political background of an understanding of the landscape in which we live.

Finally, the so-called construction of the landscape in art takes a dramatic turn in the hands of Tagle, who not only misaligns the uninformed pamphlet created by the elite, but also experiments among the geographical nooks and crannies of this country, which lies more and more subjected to extractivism.

(Images: Germán Tagle, project Futuro Esplendor, acrylic on paper, variable dimensions, 2020).

[1] CORTÉS, Gloria. El paisaje habitado. Catalogue of the exhibition “Puro Chile: paisaje y territorio”, Centro Cultural La Moneda, Santiago, 2014, pp. 198-203.

[2] GROYS, Boris. Volverse público. Las transformaciones del arte en el ágora contemporánea, (Buenos Aires: Caja Negra, 2015), p. 11.

[3] Pacha, short for Pachamama, from the Aymara and Quechua languages, meaning “World Mother” but usually translated as “Mother Earth”.

[5] GROSFOGUEL, Ramón. See in Revista Tabula Rasa (May 2016) http://www.revistatabularasa.org/numero-24/06grosfoguel.pdf

Rodolfo Andaur is a curator and manager and has therefore carried out several projects whose main objective is to ‘desertify’ unpublished stories. He is also constantly invited by recognized institutions to organize eco-territorial trips in different places in Latin America

www.rodolfoandaur.cl

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)