Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

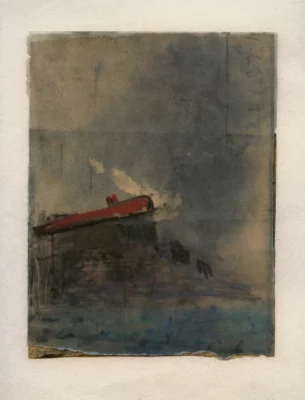

I was struck by the metaphor used by Juan Uslé (Santander, 1954) for his recent exhibition at the Museo Reina Sofía. Upon arriving in New York, he dreamily chose Captain Nemo as his alter ego: he imagined him moving forward, treading in his own footsteps, the same ones he had traced on previous nights. I couldn’t help but think of his aquatic movements amidst a submerged stone jungle, akin to our own, floating, nestled in the maternal womb. This later allowed me to better understand his constant relationship with childhood, as well as that of so many other literary characters, such as the child Benno von Archimboldi, who, in a singular way, cries underwater at the age of six, the same age at which Uslé learns of the sinking of the ship Elorrio on the coast of Cantabria, a short distance from his home, an event that serves as the seed for the present exhibition, whose title (That Ship on the Mountain) might remind us of the boats of Noah, Utnapishtim, Deucalion and Pyrrha…and it inevitably led me to think of Herzog, of that almost excessive impulse to place a ship on a summit and, in that head-on collision with another reality (perhaps at that laconic Lacanian point where the Imaginary ceases to hold and the Real emerges), to affirm that in that place the birds do not sing, but rather shriek in pain. Throughout this anthology, I have perceived neither the frustration nor the rationality capable of crushing the living and the irregular in the name of absolute geometric abstraction, as happens with the “malignant” Mason-Dixon line in Pynchon’s hands. The nature of retrospectives has this spirit of advancing by treading on one’s own footprints, as when Mason and Dixon advance in a dream until they reach an impassable riverbank, where a native reveals to them an ancient bridge inaccessible until they complete a prior task by ceasing to advance, like woodworms blindly inside a post, and end up, with luck, tracing a circle and stepping in their own excrement, the only possible beginning of wisdom, the instant in which they finally awaken. Thinking of these surveyors, with their migrant gaze in the United States, inevitably leads me to Uslé upon his own arrival in that foreign country, where it was his dreams, more than his awakening, that offered him a place to walk. And this exhibition strongly evokes that dreamlike state so clearly permeates the series begun in 1997, “I Dreamed You Were Revealing,” which, from the first time I saw it, made me think of its sinusoidal veining, gleaming like nerves of concentrated light, a light that turns blue as it touches a knot of smoke in perpetual bustle, clouds reduced by the wind to chalk strokes, leaving me in a magnetic stupor. How could I feel in some of these works a simultaneous absence and presence? I believe that, upon reflection, it relates to that idea of śūnyatā: a manifestation without a substantial core, sustained by a fleeting network of conditions and destined to dissolve in the very act of its appearance, like the Shinano (which lends its title to one of the paintings included in the exhibition), that mammoth aircraft carrier of World War II which, despite its colossal scale, vanished into thin air with the ephemeral fragility of a bubble. Upon completing the exhibition, the circularity proposed by curator Ángel Calvo Ulloa becomes clear, and upon revisiting it later, I understood how the canvases unfold as if one were entering a flotation chamber where the image pulsates in a back-and-forth motion closer to amniotic fluid than to any stable geography. The initial metaphor of Captain Nemo then became even more evident: it returned to remind me that Uslé inhabited that indifferent New York exterior, suggesting, in the manner of Melville, that the real hell is always outside. From there he built lasting submarine-like bubbles of inner refuge, from which to reconstruct his past and reactivate the raw material of his childhood; a circularity in which only a few discover that true wisdom begins by stepping in the shit.

[Featured Image: Juan Uslé, Sin título, 1987. Colección Uslé-Civera. © Juan Uslé, VEGAP, Madrid, 2025]

The exhibition Juan Uslé. That ship on the Mountain can be visited at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid until 20th April, 2026.

Tiago de Abreu Pinto is a curator and writer. He holds a PhD in Art History from the Complutense University of Madrid, with a thesis focused on the public relations agency Readymades Belong to Everyone. He has curated exhibitions in galleries, institutions, and biennials, and has participated in numerous international curatorial programs. In Spain, he was awarded the Se Busca Comisario [Curator Wanted] from the Community of Madrid. As a writer, he has published several short novels focused on artists, as well as a series of narrative texts in catalogues.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)