Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

In recent weeks, an image has caused controversy in the middle of the cultural battle that we live: the influencer Lalachus, in the special program of New Year’s Eve on the public Spanish TV, La 1, publicly showed a print of the classic Grand Prix heifer reinterpreting the traditional iconography of the Christian Sacred Heart. How provocative is this act? Who has possession of an image?

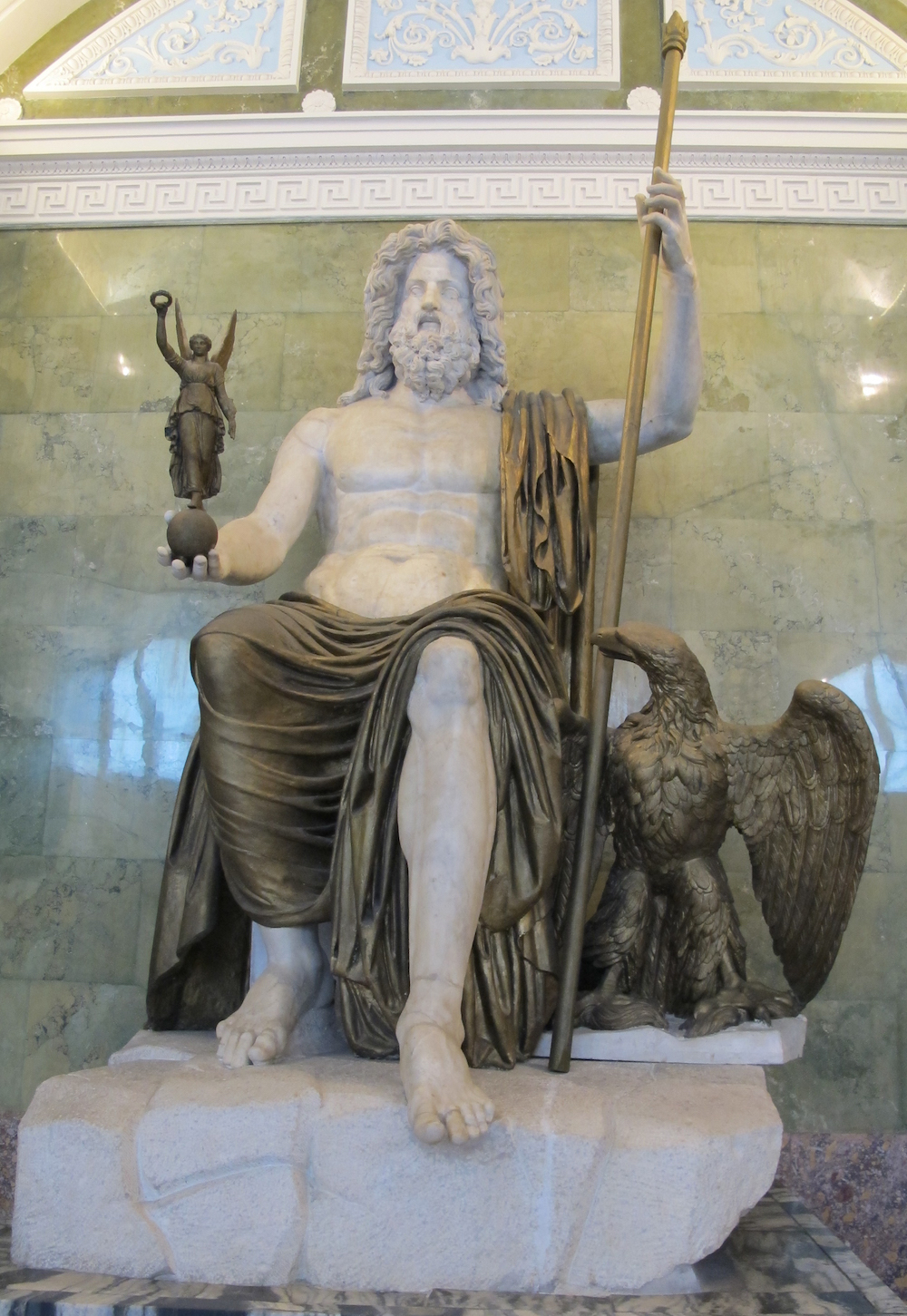

Since the Roman emperor Constantine converted to Christianity and supported the Edict of Milan in the 6th century, the persecution of his faithful ceased, and those rites that until then had remained hidden were authorized to be performed. We can find iconography relating to this early Christianity, but it was not until it was possible to make a public rite and enjoyed the support of the empire that Christianity began to create a more elaborate visual imagery to accompany its rites. One of the sources of inspiration was, in the context of the Western Roman Empire, all the iconography developed by the polytheistic religion of the Olympian gods. That is why we can see clear similarities in images from both religions: see Zeus/Jupiter enthroned as king of Olympus and the Christian Pantocrator or Maiestas domini, to give an example.

Sculpture of Jupiter enthroned, from the 1st century, in the Hermitage Museum. ©: I, Sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0

Maiestas domini by Sant Climent de Taüll, from the 12th century, in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.

For centuries, Christianity developed a wide range of images to accompany religious worship, with much more freedom compared to other visions such as the Protestant or, in the Muslim context, with Islam. This freedom in the use of images meant that, especially during the Renaissance and the Baroque, the art world took over iconographic production, and the interpretation of those artists gave us the great visual apparatus on the main biblical themes that we have today. However, these images have not been freed from a certain controversy: whether it is Michelangelo, Caravaggio or, in our contemporary context, Salustiano García, it is no longer just the what that is subject to constant revision, but also the how.

But let’s take a leap in time. In what has been classified as postmodernism, the reinterpretation of images became a common tool for artists. A clear example can be found in Pop Art, a movement characterized by the reinterpretation of the imagery developed in popular culture transferred to the context of art; or appropriationism, which appropriates objects and images and gives them a new meaning. But this characteristic is not only seen in art. Western society, so culturally visual, has drawn from the reinterpretation of images both in its most avant-garde product and in its most kitsch, to use Greenbergian terms. And it is precisely in that popular culture and in that kitsch where we find the most reinterpretative images: from the various faces that we can find in “the caganer”, the mythical figure of the manger; to the iconographic mix of the presentation of the 2024 Paris Olympics, in which the image of the Bacchanalia, the banquet of the gods and the Holy Supper were merged to represent the union of the different groups that are part of the great LGBTIQ+ community and diversity in general.

Moment of the prologue of the 2024 Paris Olympics in which this iconography on diversity is shown. ©: The Olympic Games via X.

The iconography, the image, is then transformed into an empty object. An image has no meaning without its context, without its cultural baggage; an image does not speak for itself. It needs a meaning, and this can only be addressed from its discourse. Accusing Lalachus of Christian offense for the use of an image would be to accuse the Pantocrator of an Olympic offense. Every image is subject to interpretation.

Perhaps the solution is to ask Lalachus about his intention, followed by an effort to trust his word, an awareness that we are not the center of the universe, that not everyone wants to offend us and that we are not that important. But how can we do this in the society of individualism and tribal sectarianism, where that independent individual being must position himself on one side or the other of the polarized cultural battle? Are we prepared to listen to the “other”?

In times of AI, when we can see the Pope kissing Trump; in times when we can see the president of the Community of Madrid, Isabel Díaz Ayuso, photographed as the Virgin Mary; in times of Photoshop, of the edit, of the meme, of the massive bombardment of images through social networks; in times when the image serves more than ever in the cultural battle, does this really scandalize us? Could it be that we are waiting for the slightest hint of the “enemy” to start a new battle? Could it not be, perhaps, that offense and being offended has become one of the main weapons in this cultural battle? Who has possession of an iconography in a culture that has been based, precisely, on iconographic reinterpretation for the generation of its own images?

[Featured Image: Lalachus with the ‘print’ of the Grand Prix heifer characterized as the Sacred Heart of Jesus. ©: RTVE (RRSS).]

Gerard Zamora (Sant Cugat del Vallés, 2001) holds a degree in Art History with a mention in Artistic Heritage Management (UAB), and a master’s degree in Contemporary Art History and Visual Culture (UAM, UCM, MNCARS). His research has been based on the exploration of the contemporary artistic fabric of Barcelona and Madrid. He has also participated as curator in exhibitions such as “Entre lo íntimo y lo exterior” (Galería Nueva) and “Sobre la mesa: Semióticas de la cocina” (Biblioteca MNCARS); and collaborates in publications such as A*Desk Critical Thinking.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)