Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

What Remains at Moderna Museet in Stockholm is structured by an unusual curatorial premise: a young artist, Laia Abril, was selected to map out her own artistic references, offering a visual artistic genealogy through which to understand her work. For this exhibition, she selected work by Emily Jacir and Teresa Margolles, foregrounding her feminist commitment rooted in the forensic witness. Jacir and Margolles are giants in this field who have consistently confronted inequality, violence, and contemporary colonial oppression through fearless works that expose structural faults in patriarchal and racist systems across the globe. The curatorial sensibility to current events begins at the door – rather than highlighting Abril’s project, the viewer is first invited to sit with Jacir’s Letter to a Friend, Palestine (2019). This work is not only the first, but also the last work to be seen as the viewer circulates through the exhibition. It pierces through the museum’s metaphorical walls into the ongoing colonial violence in Palestine.

Emily Jacir, Letter to a friend, Palestine, 2019 © Emily Jacir 2025. Courtesy the artist

Jacir’s film opens with a line to her friend Eyal Weizman of Forensic Architecture, in which she asks if the group has ever investigated a crime before it happened. This question inverts forensics into a continuous archive rather than something that takes place after the event. The film was made some years ago, and today, its meaning has changed. It looks back, asking us what could have been done, what should have been done, and why nothing was done. Warnings have been issued, preventative measures ignored, and catastrophes foretold. This is the chagrin of feminist discourse made visible: failed warnings, ignored complaints, and a final crime whose inevitability was always visible to those willing to see.

Emily Jacir, Letter to a friend, Palestine, 2019 © Emily Jacir 2025. Courtesy the artist

Jacir’s film operates within this temporal complexity with devastating precision. “Letter to a Friend, Palestine” constructs a personal portrait of Bethlehem through an intricate weave of image types: HD footage, degraded surveillance clips, family archives, and through the authenticity of citizen-journalism represented by the poor image. Hito Steyerl’s theorization of the poor image as a “rag or rip” circulating outside institutional approval, is here taken into the real world and real time. When Jacir intersperses sharp, carefully composed scenes with pixelated, compressed footage (the kind that circulates through Whatsapp and Instagram) she is not simply varying texture, she is rehearsing the visual vocabulary through which atrocity would come to be witnessed globally. The poor image in 2019 was already the language of citizen journalism from Palestine; by 2023, it would become the medium through which Gaza’s genocide flooded our screens in real time.

Emily Jacir, Letter to a friend, Palestine, 2019 © Emily Jacir 2025. Courtesy the artist

The film’s narration moves with deliberate intimacy between scales of violence. Jacir recounts the 1948 Nakba and the ongoing occupation with the same diaristic tone she uses to describe walking her dog past a checkpoint, the mundane impossibilities of leaving one’s front door under military surveillance. The structural violence that saturates her days points to sheer accumulation of uncountable crimes. Her voice traces the geography of Dar Jacir, her family home in Bethlehem, as a contested territory that is also deeply personal. The street itself becomes the protagonist and victim as it is cut up, a wounded urban fabric.

Emily Jacir, Letter to a friend, Palestine, 2019 © Emily Jacir 2025. Courtesy the artist

What makes the work prophetic is not supernatural foresight but the simple, terrible fact that nothing about the current genocide was unpredictable. Jacir’s film from 2019 contains all the mechanisms of 2023’s catastrophe: the dehumanization, the impunity, the international complicity, the documentation that fails to prevent anything at all. To watch it now is to experience forensic déjà-vu, the frightening recognition that the evidence was always there.

What Remains, installation view. Photo: My Matson/Moderna Museet

Abril’s contribution, On Rape (2022), the second chapter of her ongoing project “A History of Misogyny,” operates within a different but related forensic register. The photographs are clinical: black-and-white images of clothing that symbolizes the institutions (and cultures of rape) that failed them and allowed the crimes to happen, arranged with the cool precision of evidence photography. The list continues: a military unifrom, a Catholic religious habit, a winter coat, a summer dress, full coverage, everyday fabric. The work systematically dismantles the victim-blaming trope that women’s clothing invites assault, presenting a global taxonomy of patriarchal violence that recognizes no dress code.

Laia Abril, left: Ala Kachuu (Bride Kidnapping) Kyrgyzstan; center: Military Rape, US; right: Church Rape, Argentina. Series On Rape, 2022 © Laia Abril 2025. Courtesy the artist and Les filles du calvaire, Paris

The conceptual photography format Abril employs, in which an object serves as a proxy for an absent body, is a metaphor for institutional silence against the everyday war on women that has been taking place for centuries. Today, whether it is the trend of trad-wives, or patriarchal YouTube men’s-rights influencers, feminist achievements are being unwoven by persistent mysogino-fascist forces. Abril’s project shares a methodological base with forensic science as well as conceptual photographic practices stemming from the 1970s. Yet, where much evidence photography aims toward prosecution, Abril’s images acknowledge a grimmer reality: these are crimes for which the judicial system has already failed. The clothing becomes both evidence and memorial, document and protest against the uselessness of evidence. The clinical presentation accumulates horror through repetition. Each photograph is a case study; together they form an indictment of systemic failure that remains unaddressed and unquestioned in deafening institutional silence.

Laia Abril, installation view photographic series On Rape, 2022 © Laia Abril 2025. Photo: My Matson/Moderna Museet

What Abril shares with Jacir is an understanding of how inured our society has become to violence, how the testimonial image has become banal, and how necessary these counter-archives become when the institutions not only fail to gather, but erase evidence as irrelevant. The women’s testimonies reproduced through these photographs speak from the aftermath, from the space where prevention has already failed and only (silenced, repressed, and gaslit) witness remains. This is the temporal trap of feminist forensics: the gathering of evidence for trials that may never come, and even if they do, will never scratch the surface of justice.

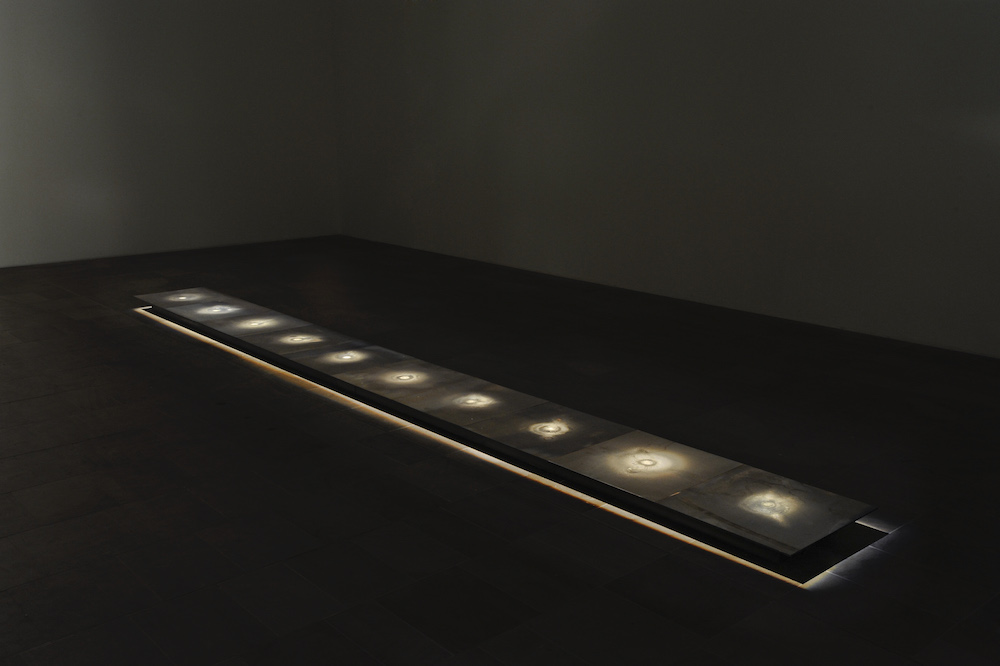

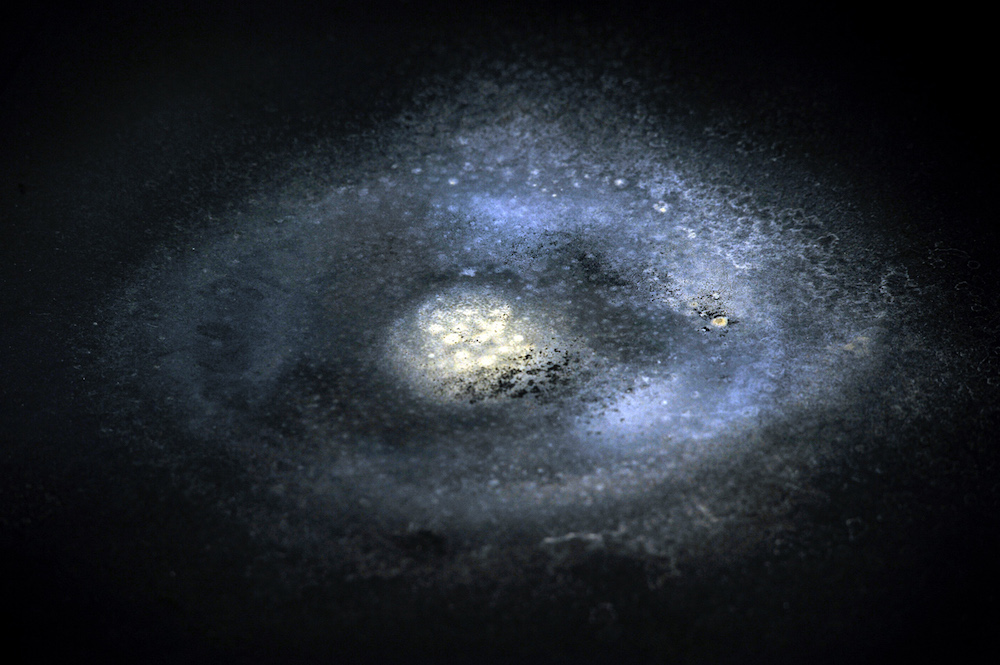

Teresa Margolles’ Plancha (Estocolmo) (2010/2025) literalizes this arrival-after into visceral experience. It lies tucked away behind a temporal wall that provides the hidden conditions of a laboratory, a back-alley, and an eerie privacy to the viewer who inhales Margolles’ gathered traces. In Spanish, Plancha, means “iron” and the sculpture is composed of a series of hot metallic plates over which a perforated tube slowly drips bits of murky water. This liquid comes from what the artist mopped up from crime-scenes around Stockholm. The water is replete with dirt, dust, and the possibility of human remains. As it drops, the water immediately vaporizes with a sharp hiss and spreads into the surrounding air.

Teresa Margolles, Plancha (Estocolmo)/Hotplate (Stockholm), 2010/2025 © Teresa Margolles 2025. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich/Paris

The work creates an atmosphere in the most literal sense: an environment one breathes, that enters the body uninvited. Margolles, who trained in forensic science, understands that evidence is not merely visual but atmospheric, that violence leaves residues society works desperately to clean away. Crime scenes are scrubbed, bloodstains removed, sidewalks hosed down, the city’s immune system works to expel signs of its own wounded condition. Death must remain invisible in the buzzing garden of capitalism. The original version of “Plancha” (2010) addressed femicide in Ciudad Juárez and maps a transnational cartography of disposable lives stemming from society’s blindness towards the threats that women face on a daily basis.

Teresa Margolles, Plancha (Estocolmo)/Hotplate (Stockholm), 2010/2025 © Teresa Margolles 2025. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich/Paris

Margolles shows how death surrounds us if we choose to see it, how quickly society conceals violent traces from urban space and from collective consciousness. The water, collected from sites most people pass without acknowledgment, becomes a ghost made tangible. The heated plates create a transformation of liquid into vapour that mirrors the way that violence disperses into the social fabric. It is not eliminated, but spread in micro-doses of aggressions and neglect, leaving their root unacknowledged.

Abril confronts discomfort head-on, tackling words, questions, and images that we have been conditioned to look away from. She traces her political and artistic lineage in a poetic handling of a space within the museum that expands into a political force-majeure speaking directly to the needs of our times. Remains is a noun: a dress, a speck of blood, material evidence. It is also a verb: it is what speaks, reminds, and demands recognition. Abril’s selection of works implores politicians, institutions, and individuals to do anything rather than standing quietly at the side of a violated ceasefire congratulating each other for work well-done. The exhibition’s images, sounds, and space, act on the artist’s professed ethics by speaking boldly, loudly, and refusing to look away.

(Cover image: Laia Abril, installation view series On Rape, 2022 © Laia Abril 2025. Photo: My Matson/Moderna Museet)

Laia Abril Meets Emily Jacir and Teresa Margolles. What Remains

Moderna Museet, Stockholm | On display until January 18, 2026

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)