Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

In 1949, the French artist Jean Dubuffet presented the exhibition “L’Art Brut” at the René Drouin gallery in Paris. This date marks the beginning of a collecting project that revisits certain passions of the artists and activates a debate on the forms of exclusion that modern art practised: admiring and collecting popular, primitive, naïve, instinctive or visionary art productions by authors who, although they inspired the most radical artists, were not recognised as art by the avant-garde itself.

The works chosen by Dubuffet in mental health centres, workshops or domestic spaces constituted the nucleus of a future art museum in Lausanne. The project was inaugurated in 1976 and since then Switzerland has become a benchmark for Art Brut. A term that over time has slipped into a stigmatising reading of social marginality and mental health, forgetting its luminous space of freedom and the healing effects of the creative practice it represents. Visiting the Art Brut Collection in Lausanne, I was able to appreciate once again the creations of authors who fascinate me: Jeanne Tripier, Madge Gill, Marguerite Sirvis or Aloïse Corbaz. They are all part of my research on the creativity of visionary women, with works created in their inner exile in asylum centres or domestic spaces; strategies for the emancipation of women condemned to submission. A museum that for an art historian is untimely and therefore inevitably transformative.

The collections on creations outside the norm connected me with another repertoire of works that represent a spirit of innocence and freedom: the collection of Naive Art that can be visited in Benasque, in the Aragonese Pyrenees. A place nestled between mountains, like Lausanne in the Alps. The works in Lausanne and Benasque illuminate a necessary history of art from the popular language or visionary and healing creativity. An interview with the creator of the collection, Javier Santos Lloro, provides us with clues about the spirit and contents of this celebration of emotions and times of surprise.

What won’t we find in the collection of works in “Arte Ingenuo-Colección Santos Lloro”?

You won’t find anything that doesn’t have the capacity to seduce me. I am not a collector in the sense of delimiting a field of interest and aspiring to exhaustiveness. For example, I really like medieval Aragonese ceramics, but no matter how rare and well-preserved a piece is, if the pottery in question doesn’t move me I won’t let it in. You won’t find art conceived to provoke. Provocation for the sake of provocation has always seemed to me to be typical of the artist who considers that being an artist sets him above the rest.

Are the pieces in the collection the result of searches or of discoveries?

The collector is always searching. He suffers from a kind of addiction to the emotion produced by the discovery of a desired object. What happens is that you don’t always find what you are looking for, or, in other words, what you are looking for are findings, not casual but pursued.

“Naïve Art” is a concept that appeals to innocence and intuition, also to the emancipating illusion of those who produce it. Do you consider the term “inclusive”?

The term has an inclusive vocation, although it also directly excludes certain artistic manifestations. Naivety is found in the art of children, in the art of untrained adults and also in the art of those who have received formal training but who dispense with academic rigour. Directly excluded are abstract art, conceptual art, installations, videos and performance art, because they move in the realm of ideas, and concepts in themselves cannot be described as naïve.

There is a history of labels for creative productions outside the norm or “borderline academicism”: irreducible art, popular art, naïve art, art brut, outsider art, magic art, art of the mentally ill, etc. Do you think the concepts are synonymous with “non-art”?

All these expressions have pejorative connotations. It’s curious that modern art was born as a reaction to the academy and that on the other hand the academic criteria is followed to scorn art produced by those who have not been trained. Modern artists reacted against the classical teaching of the fine arts and were inspired by primitive art, the art of children and primitive art, but it seems that it was one thing to be inspired and quite another to place themselves on an equal footing. The trained artist may renounce the use of rules, but the fact that he knows them is as if he were above the untrained.

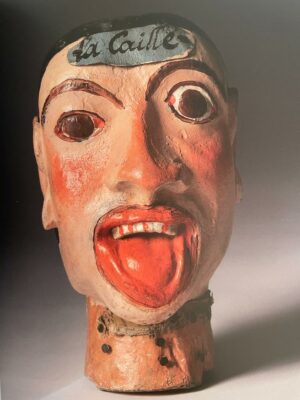

In the collection there are different types of creations ranging from paintings to masks, from ceramics to automatons, from posters to school notebooks, from tin soldiers to small historical sculptures, from academic leftovers to auto-didactic ones. In which aesthetic space is the centre of the solar system of the collection?

There is no central piece. Art is a language and depending on your state of mind you are more permeable to some manifestations or others. I like to exhibit the objects on an equal footing. I don’t like to highlight one work more because its market value is higher than another. The collector lives with the objects as if they were his own family. Sometimes an object can tell you more than a person.

Visiting the CABLausanne museum, I thought of your collection. In Spain, unlike other countries, we don’t have collections dedicated to this type of creativity. Do you think that the new generations are more porous to these popular imaginaries and their aesthetic dissidence?

For me this type of art is the real thing. People without training work devoid of conditioning factors. They don’t aspire to go down in history, they don’t know about fashions and they normally create their objects for their own enjoyment and that of those closest to them, with no intention of commercialising them. It is an extraordinarily free art, always conceived for pleasure and on the fringes of commercialism.

Angeles Santos, Soul Fleeing a Dream, 1929. Naive Art Collection

In your collection there are some creations by women. About Ángeles Santos, a well-known author in Spanish art, you write that we must read her imagery from other angles. Can the same thing happen with the painting of the almost unknown artist Amparo Palacios, for example?

I have found practically no references to Amparo Palacios and I don’t know what her case is. With regard to Angeles Santos and other artists, what I don’t like is that their lives are falsified to adapt them to the profile of interest. Whether a work was created by a woman or by a man, at an early age or in senescence, whether the author was impoverished or enjoyed the benefits of wealth, does not add or subtract anything from the work in question. I react against the need to create myths.

The recent incorporation of two drawings by the visionary Josefa Tolrà may open up other perspectives in the collection Arte Ingenuo. How do you assess this incorporation?

I’ve always been interested in Josefa Tolrà. I’ve been trying to get hold of something of hers for years. For me, her work is tremendously suggestive, apart from her condition as a medium. Her spirituality attracts my attention and I am interested in her connection with other artists with whom she shared this mysticism, but what seduces me are the sensations I perceive when I observe her work.

Drawings by the medium Josefa Tolrà (1880-1959). Arte Ingenuo Collection

The Arte Ingenuo Collection has an exhibition space. What are the plans for the future?

At the moment there is a permanent space open in Benasque (Huesca), and the idea is to open three other spaces. The idea is to make it a living space where classes, workshops, conferences and meetings are held. A space that promotes creation, the publication of publications, etc.

Navarrete. Tar figure. Barcelona, 1967-1981. Naive Art Collection

Based on the Javier Santos collection, the course “Naive Art. Naive and primitive”, 6 and 7 October 2023. Casa de Cultura de Benasque (Huesca). Directed by: Juan Manuel Bonet. More info here.

(Cover photo: Head of a massacre game, France.XIX. Arte Ingenuo Collection).

Pilar Bonet Julve is a researcher and teacher. She has a degree in Medieval History and a PhD in Art History from the UB, where she teaches contemporary art and design, art criticism and curating. She is interested in the overflowing and political spaces of art, she is not motivated by heraldic criticism or the vase exhibition. A specialist in the life and work of the Catalan medium and artist Josefa Tolrà, she follows in the footsteps of visionary women as an experience of new humanity. She has recently presented exhibitions on irregular creativity: Josefa Tolrà and Julia Aguilar, Les Bernardes de Salt; ALMA. Médiums i Visionàries, Es Baluard Museum, Palma; La médium i el poeta. An astral conversation between Josefa Tolrà and Joan Brossa, Fundació Brossa. Writing and editing pacifies his soul. She manages the research group Visionary Women Art [V¬W].

www.josefatolra.org

@visionarywomenart

@josefatolra

@pilarbonetjulve

@artscoming

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)