Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

“It has never been as important as it is now to know the future, precisely because it is not clear.”

(“Sonámbulas”, 1884)[1].

Perhaps because contemporary sentiment is polarized between the apocalyptic predictions of capitalist realism and deep disillusionment (it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism), we are currently drawn to forms of spirituality detached from archaisms and the orthodoxy of hegemonic religions that have always maintained a monopoly on what could be called the management of the soul.

Today, a different kind of spirituality, disconnected from religious institutions, has regained strength thanks to the resurgence of knowledge from conquered and colonized territories. This is a sort of trust in embodied and incorporated magic and spirituality, which pays attention to something beyond that perversely ideological and insufficient Reason to explain the world while promoting violence and abuse under the banner of supposed rigor and objectivity.

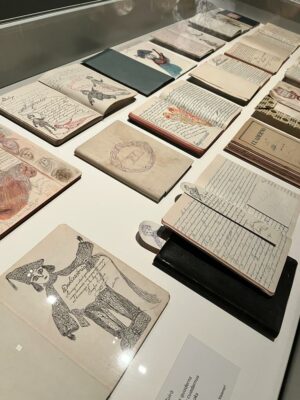

At the National Art Museum of Catalonia, in a discreet exhibition room within the Modern Art collection, there is, like a Trojan horse, an exhibition that showcases the creative activity of the Catalan medium Josefa Tolrà (1880-1959) and the English medium Madge Gill (1882-1961). Patiently awaiting us there are a series of notebooks, embroideries, and drawings made with domestic materials (paper, pen, notebooks, fabrics…) that not only demand our attention to be understood but also require a different attitude from what dominant discourses have accustomed us to. The works of these two women, who never met but shared extraordinary affinities and concomitances, invite us to reflect on how we relate to spirituality and also to artistic practice and the museum institutions that seek to embrace them.

Both of their experiences began in their maturity with visionary flashes of “beings of light” after intimate experiences of loss and grief, although it quickly evolved into a life mission aimed at helping others through their mediation. Their artistic proposals go beyond the history of art. The recovery of their legacy allows us to approach artistic practice and creativity from different perspectives that dissent from the usual aesthetic narratives and open up new political spaces in modern culture.

However, I believe that two questions precede any reflection on the exhibition: How does the museum approach the work of two women who never considered themselves artists but mediums? Women who never commercialized their works, had no artistic or literary training, worked in their kitchens or dining rooms with domestic materials, and through psychic drawing or automatic writing… This is an artistic production that, more than the result of knowledge, is the outcome of a need to create and the learning that comes with it. And how does this work push us to change our conception of art and artistic practice?

Madge Gil. Untitled. London Borough of Newham.@Newham Heritage and Archives. Courtesy of Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

Today, magic-spirituality, feminism, bodies, and images form a powerful alliance that advocates thinking and living differently. Pilar Bonet, the curator of the exhibition, points out that the current feminist wave is also related to the demand for the right to one’s own and free soul, as well as a form of creativity that goes beyond predominant artistic knowledge by announcing a transformative praxis that starts with the body, sensitivity, and emotion as starting points.

One of the strengths of this exhibition is the exercise of memory to which the work and life context of these two creators invite us. Very little is said about how, from the second half of the 19th century, during the heyday of industrialization and colonial expansion, when reason and progress seemed unquestionable pillars of the society to come, a series of formulations against the dominant ways of thinking-feeling emerged. Spiritualism, from a more scientific than religious perspective, then occurred as a radical overcoming of the prevailing authoritarian and atavistic religions, but also as a way of conceiving existence suitable and conducive to the socioeconomic, political, and cultural changes advocated by modernity.

This form of spirituality, which combines ideas from early Christianity, utopian socialism, scientific innovations, and mystical and ancestral practices from colonized territories, spread rapidly throughout the industrialized world. It participated in social revolts against capitalist imaginaries and clashed with the usual religious forms and their institutions.

In those times, Charles Fourier criticized Christian morality as pessimistic and focused on suffering, a form of religion he called “mental masochism,” and proposed another one based on joy and social happiness, focused on the satisfaction of the senses and pleasure. In this line, spiritualist societies also took positions against wars, the death penalty, and slavery, actively participating in socialist, republican, and anarchist demonstrations and movements. Moreover, these practices were mainly led by women, which contributed to the revolt against the destiny (private, secluded, and submissive) that patriarchy had designed for them.

Josefa Tolrà. Figura amb mantó brodat [Figure with embroidered shawl]. Fundació Josefa Tolrà-Art Visionari @Josefa Tolrà-Art Visionari. Courtesy of Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

Currently, from the anthropological perspective of image criticism, it is also postulated that artistic experimentation is an interstitial and medial space. Thus, Hans Belting, in his book “Anthropology of Images,” uses the term “medium” to indicate one of the three constants of the elementary artistic triad (image-medium-body). For him, image and medium are inseparable. Art objects in their entirety are also mediums. Art, liberated from submission to official discourses and the Academy and its knowledge devices, becomes, with the works of Josefa Tolrà and Madge Gill, a sensitive path from which to approach those aspects of life where established codes and dynamics no longer suffice.

[1] “Sonámbulas” was an article published in La Vanguardia that is included in the book Espiritistas y librepensadoras (2018) by Dolors Marín.

[Featured Image: Booknotes by Josefa Tolrà and Madge Gil in the exhibition The guided hand, curated by Pilar Bonet at the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Photo: Júlia Lull]

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)