Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

La luz del día viene y me quiero ir a casa

Trabajo toda la noche con una copa de ron

La luz del día viene y me quiero ir a casa

Amontonando bananas hasta que llegue la mañana

La luz del día viene y me quiero ir a casa

Venga, señor contador, cuente mis bananas

La luz del día viene y me quiero ir a casa[1]

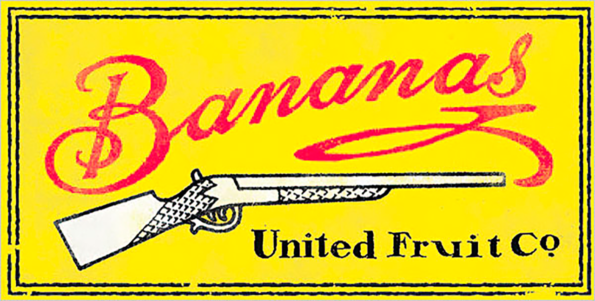

During the first years of this decade, two Brazilian magnates from the and land, Jafra and Cutrale[2], acquired the United Fruit Company[3], a company famous for its active “political imagination” of direct intervention in South America and the Caribbean through different economic and social strategies such as racist advertising campaigns, bribes, killings and coups d’état[4], there have also been dedicated to the production and exploitation of the muse of paradise, the banana[5].

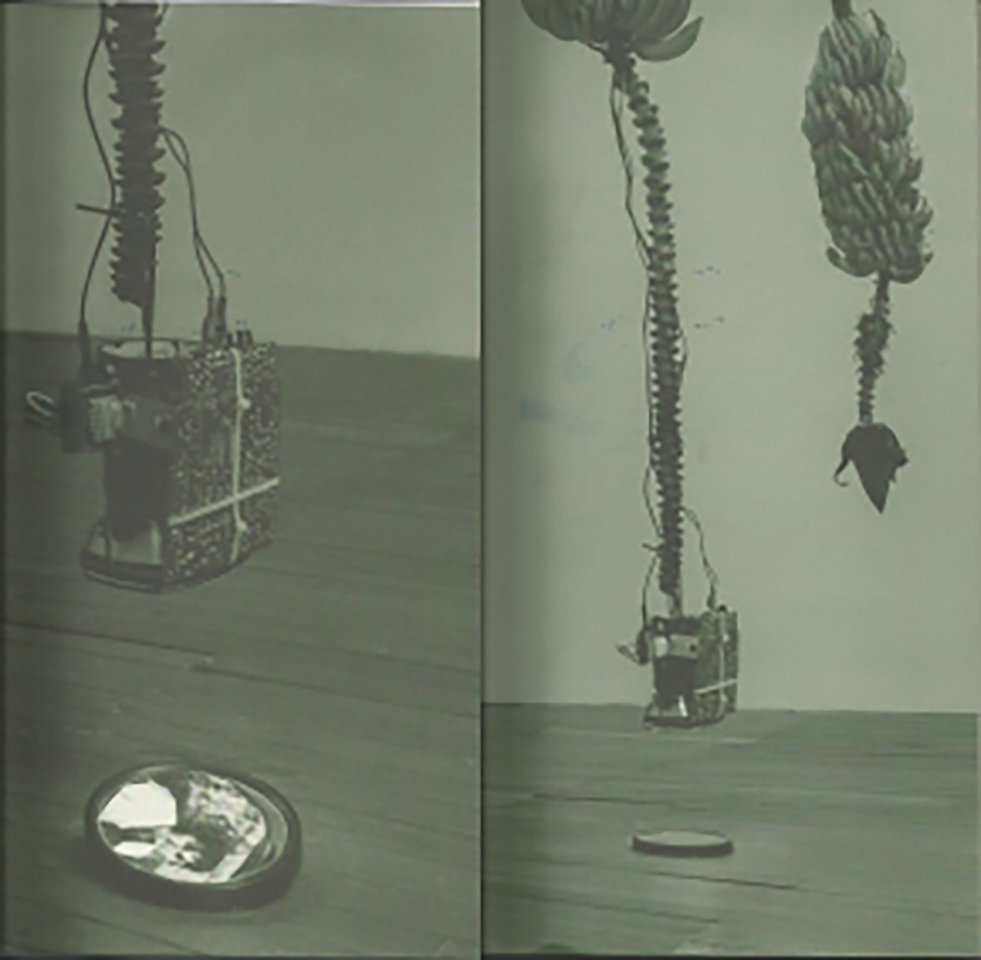

Musa Paradisíaca, J. A. Restrepo, installation, 1997/2014, Colecc

The economic system of the plantation was extended all over the American continent by the European colonists. From the 16th century onwards, this system was used continuously and uninterruptedly to this day. The enslavement of the population -whether captured from Africa or locally: indigenous, afro-descendant and afro-indigenous, mestizo was one of the favourite and most sustained forms over time. This form of labour capture was in fact implemented well into the 20th century, even though different abolitionist laws and regulations had been declared by the newly independent states during the 19th century. It is in this century that the United Fruit Company was born. Minor Keith, one of its founders, after building in Costa Rica the railroad line from San Jose to Puerto Limon acquires land for banana plantations under the name of “Mamita Yunai”[6], thus ensuring the transportation route from its plantations in the Central and South American Caribbean. In 1899, he joined Andrew Preston who had a monopoly on tropical fruit plantations, especially “West Indian” bananas, with the Boston Fruit Company which owned some 35 plantations.

The powerful impact of banana exploitation, not only in the imagination but also in the material, political and social conditions of generations, is crystallized in the famous expression “Banana Republics”. By metonymy the plantation becomes a republic and its labour hands, banana. The banana itself then becomes popular as the figuration of the body of the “sub” continent versus the “North” continent, including the intentionality of most dialogues makes it possible to replace South America and the Caribbean with Subamericabe. In this sense, the subcontinental body is at the same time abject, precarious, sweet, erotic, voluptuous, disposable, erectile, soft, tropical, mature, ugly, huge, sweaty, smelly, tasty, blackened, ripe and brownish, compared to the “Normal White Brands Continental body” that consumes us with joy, me!

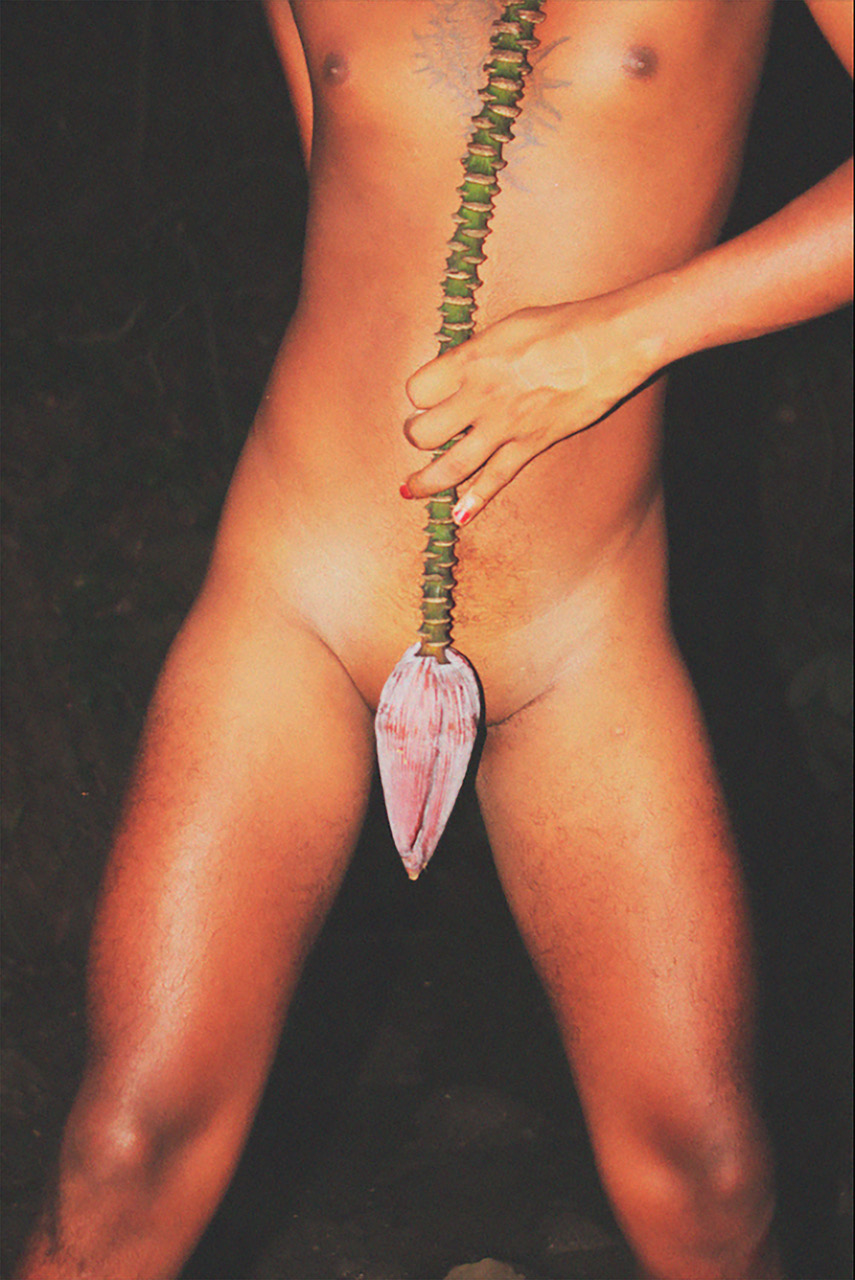

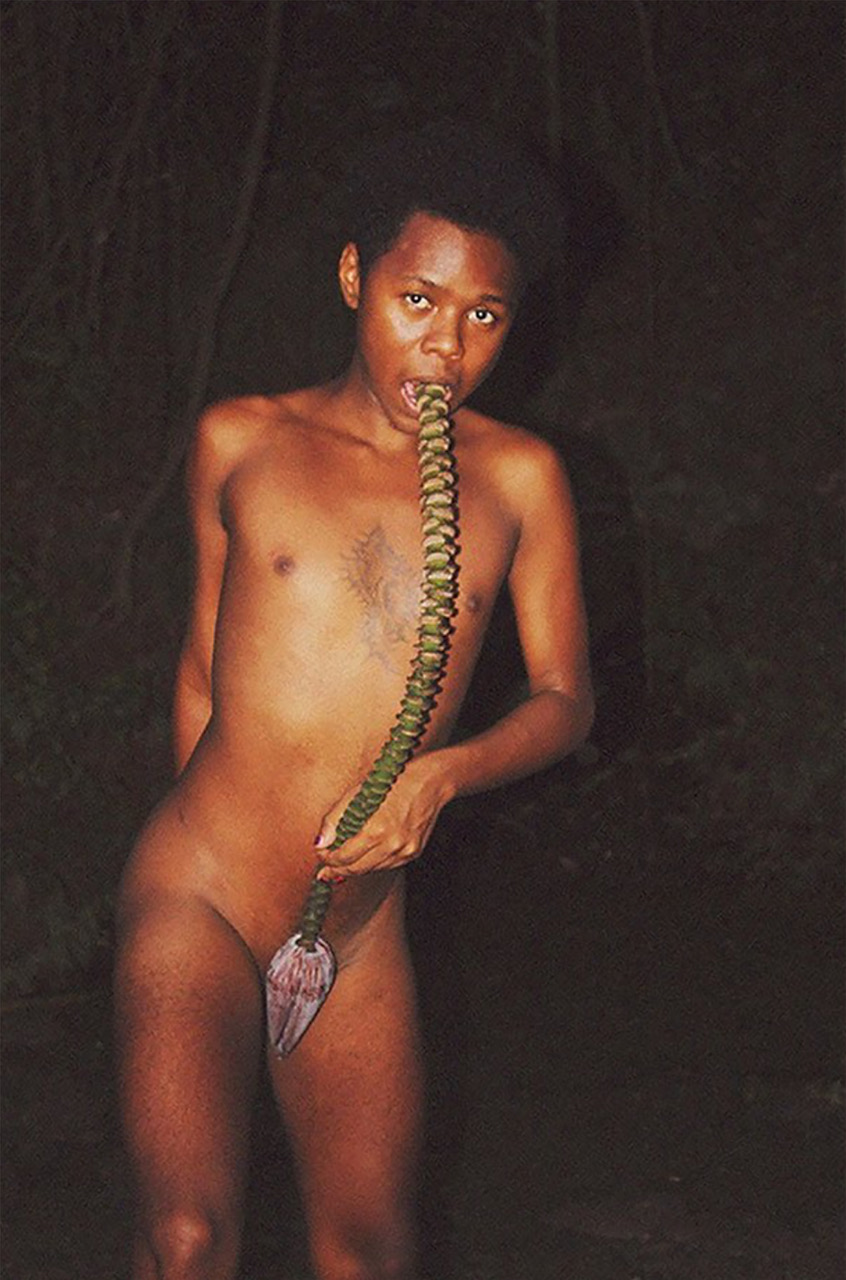

“Gastrite”,Castiel Vitorino Brasileiro. Photo performance, photo on paper, 594 x 841 mm, 2019

The banana is thus configured as the total otherness: at the same time devalued, easy, popularly edible and exotic. The wild and banana association will be served, then chimpanzees, monkeys, gorillas or simple drawings of monkeys will be added to the representation of the banana subcontinent[7].

The banana will invade everything from advertising, desserts, the creation of products banana flavour, even critical artistic movements. The impact of the banana will be and not even the most radical feminist and queer American and European movements will be exempted. The naked Banana (1966)[8] by Andy Warhol will be famous, a colour silkscreen where a banana appears on the side of its pod, and the other one peeled and exposed in pink. The feminist Shelly Mars will do a striptease in Drag King whose culminating moment will be canonized in the text “Genre and Performance” by Paul B. Preciado:

Martin is a drunken, clumsy customer who, dressed in a jacket and tie, dances to rhythm of a striptease music, to end up offering a banana that he takes out of his trouser fly to the dyke euphoric public that devours it while laughing out loud.

Two masked gorillas will eat bananas in The History of the World according to a lesbian (1988) by Barbara Hammer, the Guerrilla Girls will be the most known masked and will appear in conferences, presentations and big tabloids eating bananas.

The banana will be so big that it will cover the critical eyes that they will not see that their device, its prosthesis, its performance, its candy, its mask, its call to revolution, to the creation of new commons, its injurious appropriation, its imagination of new possible communities has naturalized the slave-like, colonial racist and despotic order in its figure.

The call for a revolution in the political imagination for some new community is like a Fido Dido T-Shirt of the late 80’s: impossible to wear a garment made for cartoons. Many times that call is made by voices that recognize the effects of patriarchy, racism and coloniality, but which do not delve into either the current production of these regimes or their effects, they name them as a given fact, in the past, and they rename it as a renewed fact in the present, and nothing more. They conjure up an us that is refers to a West and a horizon that does not understand the historical processes of coloniality in its construction, limits and racist and elitist imagination that also makes community. The speakers of these calls also abound in giving examples of the creativity of the struggles of the “minorities” and “social movements” of the “South”, a common rhetorical panegyric of the revolution we would have to make, which is in progress or has even been made, but which still requires us to return to the ranks of an “us” that does not even stand or simply expels us with brutality.

It is also usual to hear, along with this call, the super-traditional proposal of North-South bamby alliances as a way of transformation, blurring not only the very hierarchical character of this relationship and the effects of its dynamics of capture and dispossession-not only but by leaving out the naturalized social violence that these alliances, which often materialize in death, precarization or basic survival for some or legitimation and access to economic and cultural rights, for others: South —> North, respectively. Needless to say, the literalness and naturalization of such outdated expressions as “North and South” are not even questioned, even in the face of sympathetic evidence that, for example, the North magnetic is on the move for over three decades. The metaphors about the social and community transformation through political imagination have not only been captured by the colonialist neoconservative neoliberal ideologies but have become obsolete. And it’s not just because of the bug’s pandemic shock that as they say “makes a big deal out of everything,” but for the bananas.

There’s a Banana involved in imagining and making community.

Plátano, Sacchi De Santo, photograph, San Cristóbal de las Casas, 2020.

(Featured Image: Logo of the United Fruit Company)

[1] Day-oh, the banana boat song, anonymous folk song from the Bananas of the 19th century, popularized in the USA by Harry Belafonte, multiple times and with multiple purposes.

[2] Jafra, one of the world’s richest bankers, Cutrale monopolistic millionaire landowner of the soybean and the orange.

[3] When it is acquired due to its bloody history the company has been renamed Chiquita Brands International.

[4] The participation of United Fruit Company in different strikes is widely documented in South America and the Caribbean, the terrible massacre of the banana plantations in Colombia in 1928 and Ambassador Braden’s US campaign paid for by the company to influence elections in Argentina in 1946 are examples of this.

[5] Musa Paradisíaca is its botanical name, classified by Linnaeus in 1753, also known as such as banana, topo, banana, banabo, minimum, guineo (in reference to plantations African) The names muse and banana come from Arabic and the uses to name the fruit.

[6] The name by which the United Fruit Company is still known in the Caribbean. The name is burlesque of the pronunciation of “United” in Spanish.

[8] Cover of the album The Velvet Underground & Nico.

Duen Sacchi (Aguaray, Argentina). Artist, researcher, writer, Guaxu, migrant based in Barcelona. His work stresses the relationships between writing, drawing, printmaking and their forms of reproduction from a anti-colonial, anti-racist and anti-patriarchal perspective from the critical non-cisnormative spaces of the Afro-indigenous and mestizo diasporas. He constantly investigates the ancestral legacy of his non origin formal artistic practices. “Pathogenic Fictions” is his latest published book, Brumaria (2018) Rara Avis (2019). He has developed actions, residencies and presentations of his work in La Virreina (Barcelona), Tabakalera (Donostia), Matadero (Madrid) La Ene (Buenos Aires) among others. It has received the creation aid Eremuak 2018. He is part of the Equipo Estrella Frágil (SACCHI-DE SANTO) and the Ira Sudaka collective.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)